-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Olia Poursina, Jingxin Qiu, Primary intraosseous meningioma: a case of early symptomatic calvarial origin meningioma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 10, October 2024, rjae676, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae676

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Primary intraosseous meningiomas are rare extradural tumors. They are typically slow-growing, painless, and asymptomatic until they cause a mass effect. We report a case of a calvarial primary intraosseous meningioma, which became symptomatic despite a very small size. A 67-year-old female with a history of precancerous breast tissue presented with right-sided stroke-like symptoms. Computed tomography showed right parietal convexity irregularity without hemorrhage or infarct. MRI indicated a right parietal calvarial signal abnormality and dural thickening, suggesting metastases or primary osseous neoplasm. A PET scan revealed heterogeneous uptake in the right parietal skull with no other abnormalities. Histology confirmed the diagnosis of primary intraosseous meningioma. Histopathological examination is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis and treatment planning, which may involve wide-margin skull resection, radiation, or both.

Introduction

Meningiomas are the most common central nervous system (CNS) tumors, accounting for about 30% of all cases [1, 2]. Primary extradural meningiomas (PEMs) are a rare subtype of meningiomas that account for less than 2% of all meningiomas [2, 3]. Primary Intraosseous meningioma (PIOM) is a subtype of extradural meningioma that arises in bones and accounts for two-thirds of all PEMs [4]. The incidence of PEMs is slightly higher in females [5, 6], with one peak in the second decade of life and the other between 50 and 70 years old [2, 6]. Here, we present a case of parietal intraosseous meningioma that, despite its very small size, manifested with stroke-like symptoms.

Case report

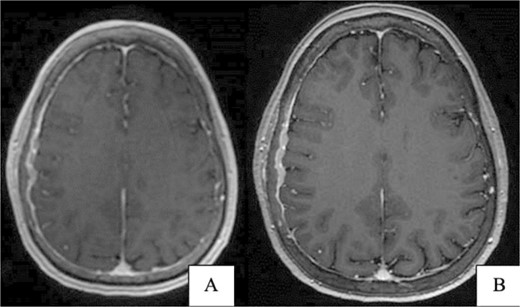

A 67-year-old female presented with transient right-sided stroke-like symptoms. The initial CT scan and MRI with and without contrast revealed a right parietal convexity heterogeneous enhancement of the calvarium with subjacent dural thickening, extending from the posterior frontal bone, concerning metastases or possibly primary osseous neoplasm. No hemorrhage or large vessel territory and no epidural mass were observed (Fig. 1). A whole-body PET-CT scan revealed heterogeneous mild to moderate abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake involving the right-sided parietal skull sclerotic lesion and no other site of abnormal uptake. She had a past medical history of right-sided breast atypical ductal hyperplasia, which was removed four years ago.

(A) Brain CT without contrast shows no acute hemorrhage or large vessel territory infarct. (B) Brain MRI without contrast: right parietal calvarial signal abnormality with subjacent dural thickening. There is no definitive parenchymal involvement.

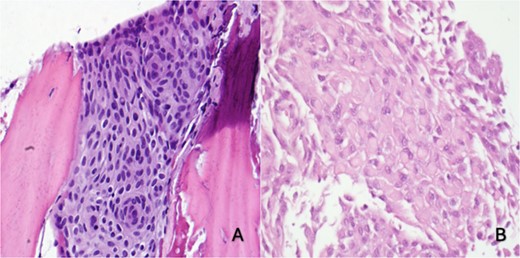

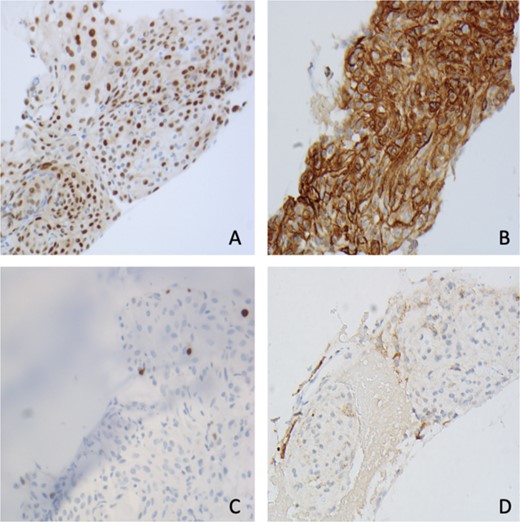

She underwent a craniectomy and skull biopsy. Gross examination revealed tan-pink soft tissue and bone fragments, with the largest specimen measuring 1.5 × 0.6 × 0.3 cm. Microscopically, the tumor showed a syncytial growth pattern with meningothelial whorls. Tumor cells were focally positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), progesterone receptor (PR), and somatostatin receptor 2A(SSTR2A), with Ki67 < 1% (Fig. 2). During the subsequent surgery two months later, the tumor-involved skull and adherent dura were removed through a wide excision, and a 10 × 10 cm cranioplasty was performed.

(A) Right skull and scalp partial thickness craniectomy shows syncytial growth pattern with meningothelial whorls favoring intraosseous meningioma (H&E 400×). (B) Skull and dural excision: focal rhabdoid morphology (H&E, 400×)

Pathology showed a sheet-like growth pattern with rare prominent nucleoli, a mitotic count of less than 2 per 10 high-power fields, Ki-67 15%–20%, and a focal rhabdoid morphology Fig. 3). Molecular testing was negative for CDKN2A homozygous deletions and Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations. The patient was stable after the surgery and the six-month follow-up with no recurrence or residual extra-axial lesions.

Immunohistochemistry shows tumor cells are positive for (A) PR, (B) SSTR2, (C) Ki67 < 1%, and (D) EMA (400×).

Discussion

The clinical presentation of PIOMs depends on their size and location [6, 7]. The most common presentation of calvarial-origin PIOM is a slow-growing asymptomatic mass that grows until it becomes large enough to cause a mass effect. Headaches are the second most frequently reported symptom [8]. The pathogenesis of PIOM is still unclear and controversial. Some authors suggest that its origin is related to the intracranial suture line, where a portion of the dura mater or arachnoid cap cells become trapped in the suture line due to trauma, embryonic development, or head molding at birth [2].

Microscopically, the tumor is most often WHO grade 1 [5, 9] and exhibits a syncytial growth pattern with meningothelial whorls and is positive for EMA, PR, and SSTR2A [10]. These tumors can also be subclassified based on their anatomical location into convexity and skull base lesions [4]. The most common locations are the orbital cavity and frontoparietal area, most commonly in the frontal bone (29.1%) [11]. The optimal treatment is surgical excision, with a reported recurrence rate of 12.6% to 22% postsurgery [12]. The skull base meningiomas have a higher recurrence rate due to the challenges in achieving complete resection in these areas [12]. However, Ueno et al. reported a case of transitional meningioma (WHO grade I) convexity PIOM that recurred seven years after the surgery [2]. Chen et al. reported even histologically benign but unresectable PIOMs may exhibit malignant changes over time [3]. Several recent studies highlight the significance of molecular features in assessing the risk of recurrence [13]. The 2021 WHO CNS5 classifies meningiomas into three grades using both histopathology and molecular features. Grade 1 tumors with mutations like pTERT or CDKN2A/B deletion are upgraded to grade 3, indicating more aggressive behavior and higher recurrence risk. This shift highlights the importance of molecular profiling for accurate tumor grading and treatment planning [2, 13]. In our case, molecular testing for CDKN2A deletions and TERT mutations was negative. While reassuring, these results still underscore the need for preventive management and emphasize the role of molecular testing in personalized care and treatment decisions.

Tumor location is also associated with specific underlying mutations. Convexity and most spinal meningiomas frequently exhibit 22q deletions and NF2 mutations. In contrast, skull base meningiomas are often characterized by mutations in AKT1, TRAF7, SMO, and/or PIK3CA [9, 13]. PIOMs can also be subclassified into osteoblastic, osteolytic, or mixed types and mimic a wide range of benign or malignant lesions, either metastatic or primary bone tumors [2, 10, 14]. The osteolytic subtype is less frequent in PIOMs, with reported rates ranging from rare to 35% [2]. Hyperostosis is more common in low-grade meningiomas. In contrast, a mixed hyperostotic/lytic pattern is typically associated with higher grade meningiomas [15]. Some of the differential diagnoses include osteosarcoma, eosinophilic granuloma, Paget disease, osteoblastic skull metastasis, osteoma, fibrous dysplasia, en plaque meningioma, plasmacytoma, giant cell tumor, hemangioma, epidermoid cyst, osteogenic sarcoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, fibrous dysplasia, or infection [16]. Imaging studies, clinical presentations, and histological evaluations are essential for differential diagnosis [10]. Each of these conditions may show bone involvement or destruction; however, they vary in their underlying mechanisms and clinical progression. The diagnosis can be challenging and histologically misdiagnosed. Immunohistochemistry is very useful in distinguishing PIM from a primary or secondary bone tumor [16]. Blood tests, such as alkaline phosphatase levels, can assist rule out important differential diagnoses such as Paget’s disease of the bone [5]. The combination of MRI and CT scans helps the diagnosis of ICM in most cases [17].

Our case was diagnosed as meningothelial meningioma, WHO grade 1, and was reported as a heterogeneous, well-defined enhancement in MRI. The dura-tail sign, characterized by thickening of the dura adjacent to an intracranial pathology on MRI, is a useful marker in diagnosing meningiomas. It is typically associated with convexity meningiomas but can also be present in PEMs and is not indicative of dural origin, although PEMs can invade the dura and make a dural tail sign [2, 4, 11]. In our case, there was no sign of a dural tail, which supported the extradural origin and differentiated it from typical convexity meningioma extending outside the dura. Histopathological studies report that the rate of dural infiltration in PIOMs ranges from 26% to 87.5%, while radiographic studies indicate a range of 60.0%–68.8%. These findings suggest that PIOMs have a significant propensity to infiltrate the dura [2]. To prevent future recurrence or progression to a malignant grade, management is often wide excision and long-term follow-up [2, 7]. Most calvarial meningiomas are benign and slow-growing, but compared with intracranial meningiomas, PEMs are more prone to develop malignant changes [4]. The treatment of choice in symptomatic cases is extensive surgical excision. Total resection of the dura at the craniotomy site should be considered, as PEMs and PIOMs could recur even if intraoperative findings do not show any dural invasion. Adjuvant therapy is recommended for unresectable or partially resectable symptomatic tumors or those with malignant or atypical histology. Treatment options may include radiation therapy such as external beam or Gamma Knife surgery, as well as chemotherapy and bisphosphonate therapy [2, 14].

Recurrence has been reported in atypical or malignant intraosseous meningioma within two years and in histologically benign tumors within 10 years after the resection [4, 14]. Limited long-term follow-up information is available for PIM due to their uncommon nature. However, studies indicate that the recurrence rates for benign meningiomas originating from the calvarium vary between 12.6% and 22% [12]. Therefore, regular imaging surveillance and close monitoring of patients are crucial to evaluate the extent of resection, early detection of recurrence or malignant progression, and timely intervention [10]. In cases of suspected meningiomas or those classified as WHO grade 1, annual MRI scans are recommended for 5 years. Following this period, the frequency of the scans may be increased to every 2 years [17] and continued monitoring for any neurological changes or tumor regrowth is recommended.

PIOM diagnosis can be challenging due to its rarity and asymptomatic progression. Imaging studies are essential in identifying PIOMs; however, histopathology remains the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis. Due to the rarity of these tumors, it is crucial to have a high suspicion in the differential diagnosis. Timely and accurate diagnoses can significantly improve treatment outcomes, highlighting the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between radiologists, pathologists, and neurosurgeons in developing effective treatment plans for individual patient needs. Careful long-term follow-up is recommended regardless of the pathological findings or degree of gross removal.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding

None declared.