-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jesús Eduardo Prior Rosas, Moisés Alejandro Perdomo Galván, Paul Robledo Madrid, Andrés Armendáriz Rodríguez, Carol Atzimba Zepeda Carrillo, Laparoscopic primary right omental torsion: a challenging diagnosis in acute abdomen: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf463, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf463

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Omental torsion is rarely diagnosed preoperatively and often misdiagnosed with other pathologies as acute abdomen, the most common of them being acute appendicitis. The current choice for the management of omental torsion is laparoscopic surgery. We present a case of a 35-year-old male with 48 h of acute abdominal pain mainly located in the epigastrium but then progressively migrated to the right iliac fossa. Abdominal CT showed mild thickening of the appendix. It also shows that the greater omentum locally hyperdense fat. The patient was brought to the operating room for diagnostic laparoscopy, revealing a primary right omental torsion. The patient was discharged 48 h later with no complications.

Introduction

Omental torsion is a very rare cause of acute abdomen that often leads to misdiagnosis. It was first reported by Eitel in 1899. It remains a rare diagnosis, with an incidence of 0.0016% to 0.37%. Only 0.2%–4.8% of the cases of omental torsion are diagnosed preoperatively, highlighting how rarely its diagnosis is made using imaging modalities [1].

Torsion of the greater omentum is classified as primary or secondary, the latter being far more common. Secondary torsion of the greater omentum is associated with causative conditions, such as adhesions, cysts, inguinal hernia, inflammation, previous laparotomy, trauma, or tumor [2].

It primarily affects middle-aged adults (30–50 years); it affects males twice as frequently as females, especially those who are obese [3].

The affected part of the omentum is usually on the right side of the midline because it is more mobile than the left side of the omentum. Longer duration of the torsion can lead to omental necrosis. There is no specific clinical presentation of this condition. It mimics different pathologies presenting acute abdomen like acute appendagitis, cholecystitis, incarcerated hernia, diverticulitis, and ovarian torsion, most commonly acute appendicitis [4].

Case report

We present a case of a 35-year-old male with no significant comorbidities and no previous records of surgical intervention. The patient presented at the emergency with 48 hours of abdominal pain. The initial pain was diffused and mainly located in the epigastrium but then progressively migrated to the right iliac fossa with no other symptoms. The abdominal examination revealed tenderness with signs of peritoneal irritation in the right iliac fossa.

At the admission, his laboratories were TP 12.3 s, INR 1.07 s, TTP 30 s, leukocytes 10.4 μ/l, neutrophils 76.8 μ/l, hemoglobin 17.6 g/dl, hematocrit 52%, platelets 304 μ/l, fibrinogen 573 mg/dl, glucose 101 mg/dl, bun 11 mg/dl, urea 24 mg/dl, creatinine 1.0 mg/dl, NA 136 mg/dl, K 4.4 mg/dl, CL 98 mg/dl, protein C reactive 1.2 mg/l, procalcitonin 0.036 ng/l. Abdominal CT showed mild thickening of the appendix, which was not enough to diagnose appendicitis definitively. However, it did show that the greater omentum locally hyperdense fat, which was not consistent with peri-appendiceal inflammatory changes seen in appendicitis. The patient was brought to the operating room for a diagnostic laparoscopy (Fig. 1).

(a) A simple coronal and (b) axial CT showing the density of intra-abdominal fat on the right side was markedly increased, indicating inflammation of the greater omentum.

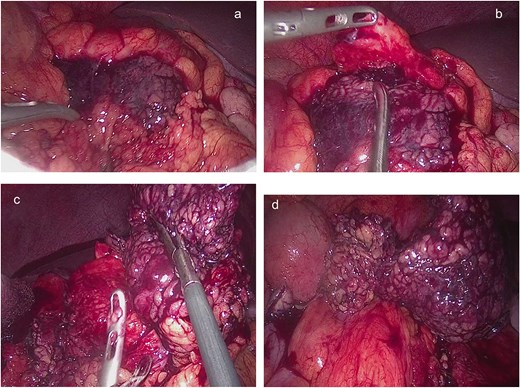

Intraoperative findings: we encountered a twisted and congested segment of the greater omentum with zones of necrotic changes and blood clots covered with an ischemic portion of omental fat on the right side transverse colon; the necrotic omental portion was dissected with a harmonic dissector and removed from the abdomen (Fig. 2).

(a, b) Twisted segments of the greater omentum with necrotic-looking patches of blood clots covered with an ischemic portion of omental fat on exploring the omentum on the right side of the transverse colon. (c, d) Necrotic twisted omentum resected.

The appendix looked grossly normal, so we decided to perform an appendectomy to prevent the future risks of representation with acute appendicitis in this young patient.

A standard appendectomy was performed with no concerns.

Postoperative recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the second postoperative day. The pathology report confirmed a normal appendix and demonstrated adipose tissue fragments showing ischemic and hemorrhagic changes consistent with omental fat infarction. The patient was discharged from the surgical services with no further follow-up.

Discussion

First described in 1899 by Eitel. However, Bush is credited with the first reported case in 1896. After Bush’s description, fewer than 300 cases have been reported in the literature, of which fewer than 26 were treated by laparoscopic surgery. Torsion of the greater omentum is a rare cause of acute abdominal pain with an incidence of 0.0016% to 0.37% and is the cause of 1.1% of cases of abdominal pain [5].

It is classified as primary and secondary. Primary or idiopathic torsion is a rare condition. Several predisposing conditions have been found: obesity with accumulation of omental fat, bifid or accessory omentum, narrow omental pedicle, venous redundancy, and finally a sudden change in body position or local trauma that increases the intraabdominal pressure. Secondary torsion is more common and is associated with abdominal pathology like inguinal hernia (most common), tumors, cysts, internal or external herniation, foci of intra-abdominal inflammation, and postsurgical wound or scarring [6, 7].

The most common point of omental fat torsion is around the distal right epiploic artery due to the increased length and mobility on the right side of the greater omentum; this would explain the predominant clinical presentation with right-sided abdominal pain compared to the left one, which is well-fixed because of gastrosplenic and splenocolic ligaments. Omental torsion generally occurs as a volvulus on its long axis, initially causing venous congestion and edema, causing hemorrhagic infarction, and finally omental necrosis [7, 8].

The pain in omental torsion and infarction is of sudden onset, is continuous, and the severity increases with time and movement. In physical examination, tenderness and rebound in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen are frequently found. In most cases, omental torsion is often misdiagnosed as appendicitis, diverticulitis, or cholecystitis because right-sided abdominal pain is a common complaint in all of them [9]. In children, the differential diagnosis may also include acute intussusception, mesenteric lymphangitis, allergic purpura, and ascariasis [10].

An important characteristic of omental torsion is that gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, are less common. When these symptoms are absent in patients with abdominal pain, it would be worth considering nongastrointestinal diseases. Constant nonradiating pain, which increases in severity over time, is the earliest symptom of omental torsion. Leukocytosis and elevated body temperature could also occur, as well as a palpable mass, depending on the size of the segment involved [11].

Ultrasound typically shows a solid, noncompressible, hyperechoic mass found under the site of highest sensitivity. CT scan reveals a focal inflammatory mass of fatty density with streaks that form a whirling pattern, corresponding to fibrous bands or dilated veins. The integrity of other abdominal organs is important, as a normal appendix, gallbladder, and pelvic cavity can rule out other conditions and make omental torsion a likely diagnosis [12].

Differentiating epiploic appendagitis from omental torsion is more challenging because both show a fatty mass on CT. However, the location of the fatty mass may serve as a clue. Epiploic appendagitis is usually discovered adjacent to the colon, whereas omental torsion is situated farther away from the colon, usually at a more medial location [13].

Due to its rarity, the treatment of choice remains controversial with no clear consensus or guidelines, especially with the absence of prospective comparative studies [14].

The potential effectiveness of conservative management with antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medication is controversial. In a systematic review, Medina-Gallardo et al. [15] present a review of the literature, including 146 patients who reported a high rate of success in the resolution of symptoms (84.1%). However, when surgical treatment is chosen, hospital length of stay is shorter (2.5 days vs. 5.5 days, P = .00). In addition, patients in whom conservative treatment failed and underwent laparoscopic surgery were more likely to need conversion to laparotomy (27.2%).

Conservative treatment predisposes to local complications, abscesses, adhesion syndromes, or even to the omission of an underlying condition that can be masked by the symptoms and imaging data of an epiploic torsion. Surgical treatment consisting of segmental omentectomy can be performed by the laparotomy or laparoscopic approach [8]. We prefer the advantages of laparoscopic techniques, which include the following: complete examination of the abdominal cavity to confirm diagnosis, facilitation of aspiration and washing of the peritoneum, and minimization of surgical invasiveness, postoperative pain, and wound-related complications.

Conclusion

Omental torsion is an uncommon cause of acute abdomen. A high level of suspicion is required, along with imaging suggestive of this pathology. However, there is controversy regarding nonsurgical treatment. We prefer the laparoscopic surgical approach to prevent complications and reduce hospital stay.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.