-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Khalid Abu aagla, Abdulhakim Alsaadi, Mudathir Bafadni, A hidden menace: incidental finding of leiomyosarcoma of the inguinal canal, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf478, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf478

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Leiomyosarcoma is a rare but aggressive malignancy of the paratesticular region. This case report presents a 74-year-old male who presented with an asymptomatic inguinal mass, ultimately diagnosed as a leiomyosarcoma of the spermatic cord and underwent a radical orchidectomy. This case highlights the challenges in diagnosing paratesticular sarcomas, particularly in the absence of specific symptoms. Early diagnosis and radical surgical resection are crucial for optimal outcomes. Adjuvant therapies, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy, may be considered in select cases, but their role remains uncertain.

Introduction

Leiomyosarcoma is a type of malignant mesenchymal neoplasm with smooth muscle differentiation; it forms 10%–20% of all newly diagnosed soft tissue sarcomas [1]. Its incidence rises with age and peaks during the seventh decade of life. The spermatic cord is the most common site for paratesticular sarcomas [2], accounting for 10%–30% of all lesions. Leiomyosarcoma is the para-testis’s second most common malignant mesenchymal tumor after liposarcomas [3]. Most paratesticular sarcomas are aggressive, with a high tendency to recur locally and to disseminate distantly [4]. Early-stage soft tissue sarcoma offers a high cure rate. However, diagnosis at advanced stages with extensive local or metastatic disease significantly diminishes the likelihood of cure [5]. This case describes an incidental finding of leiomyosarcoma in an elderly male admitted for another non-related procedure.

Case report

A 74-year-old male presented for the removal of a left ureteric stent, inserted 6 weeks prior, to manage an obstructing left ureteric stone under urology care. During his admission, he complained of a newly developed, asymptomatic right inguinal mass that he believed to be an inguinal hernia.

On physical examination, a firm, non-reducible, partially mobile mass measuring ~5 × 3 cm was palpated in the right inguinal canal. The mass did not transilluminate, had no cough impulse, and was nontender. The testicle appeared normal. No palpable regional lymph nodes. Hematological, biochemical tests, and urinalysis were normal.

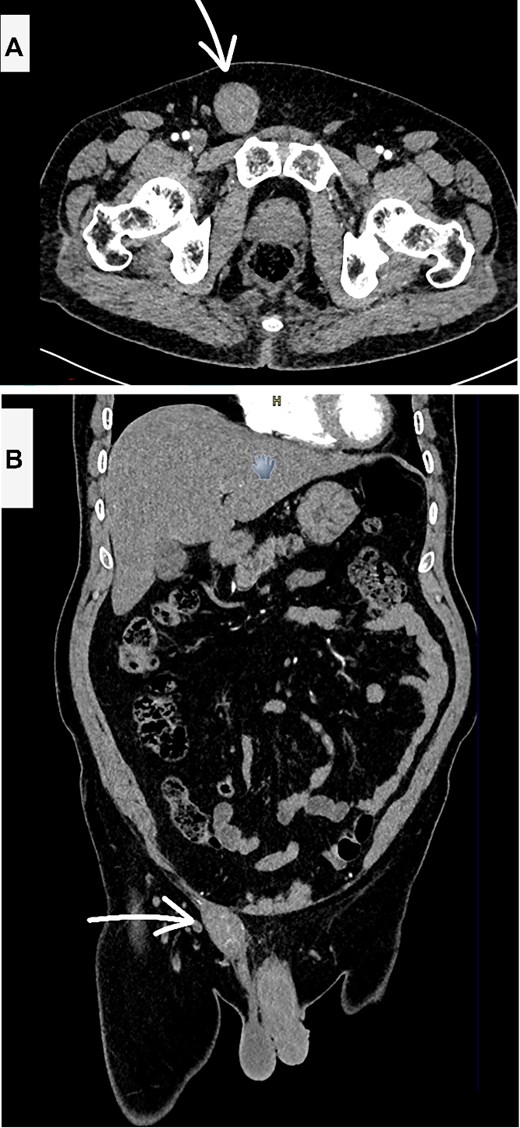

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a heterogeneous, enhancing soft tissue mass lesion along the right spermatic cord (Fig. 1). No suspicious lymph nodes, testicular abnormalities, or retroperitoneal masses were identified. The liver, spleen, and lungs were unremarkable.

Contrast enhanced CT scan abdomen and pelvis (A—axial and B—coronal views) showing the suspicious inguinal mass (white arrow).

Given the high suspicion of malignancy, the patient was offered a radical resection with potential orchidectomy if necessary. However, the patient initially declined orchidectomy and consented only to resection of the mass itself.

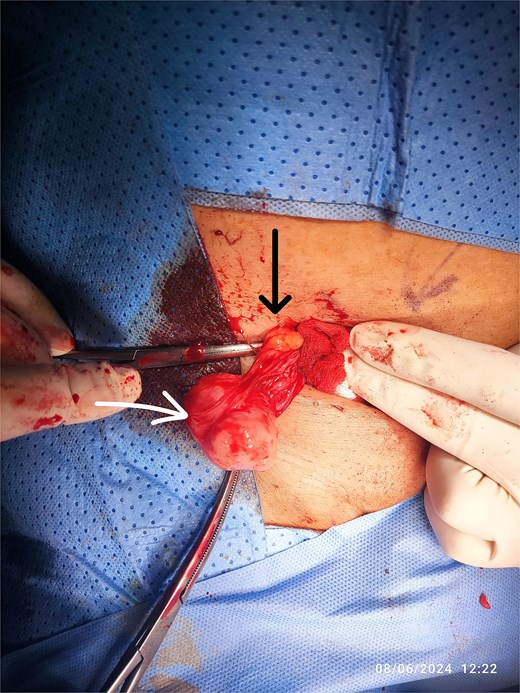

A right inguinal incision was made, and the mass was identified within the spermatic cord. The encapsulated mass was excised completely with a safe margin (Fig. 2). Histopathological examination revealed an intermediate-grade leiomyosarcoma with a positive resection margin, with mitosis (20/1000 cells); immunohistochemistry shows Ki67—2%, caldesmon—positive. In light of the positive margin and the malignant nature of the tumor, the patient underwent a second surgery 2 weeks later.

Intraoperative view of the RT inguinal mass (white arrow), cord structures (black arrow).

This procedure involved a wide local excision of the tumor bed down to the transversalis fascia, high ligation of the cord at the level of the deep ring, along with an orchidectomy, and excision of previous surgical scar (Fig. 3). The inguinal floor was reinforced with mesh to prevent future hernia formation.

Radical orchidectomy specimen, with marked inferior resection margin.

The patient recovered well from the second surgery, and his sutures were removed 2 weeks postoperatively. The second histopathology report confirmed complete resection with negative margins.

The patient was subsequently referred to the oncology department for further evaluation and management.

Discussion

The majority of malignant neoplasms of non-testicular origin are sarcomas. Primary paratesticular tumors are uncommon, constituting only 7%–10% of all intrascrotal tumors [6, 7]. They primarily arise from the spermatic cord. While most paratesticular tumors are benign, such as lipomas, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, and leiomyomas, malignant tumors, including liposarcomas, leiomyosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, fibrosarcomas, and angiosarcomas, are also observed [3].

Leiomyosarcoma originates from smooth muscle cells in the paratesticular region. It can spread locally by directly infiltrating adjacent tissues or distantly through hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination [8]. Nodal metastasis can occur to the external iliac, hypogastric, common iliac, and para-aortic lymph nodes. Hematogenous dissemination primarily affects the lungs or liver [9].

Paratesticular sarcomas typically originate from the spermatic cord, testicular tunica, epididymis, external inguinal ring, or scrotal wall. Their location above or below the external inguinal ring determines whether they manifest as inguinal or scrotal masses, always distinct from the testis itself [3, 4].

Preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma in this region is difficult. Typically, patients present with a unilateral, painless, or painful inguinal or scrotal mass, which may be accompanied by a hydrocele. In some cases, the initial presentation can be an acute scrotum due to tumor necrosis or hemorrhage [10]. Due to the low prevalence of sarcomas relative to hernias, inguinoscrotal lumps are not commonly suspected as malignant, leading to diagnostic delay [11]. Ultrasound is the primary diagnostic modality. Findings typically include a heterogeneous, hypoechoic mass with increased vascularity on Doppler. Preoperative ultrasonography, extending to the scrotal region, can help characterize inguinal lumps. However, definitive diagnosis typically relies on histological analysis, often requiring an incisional or excisional biopsy [12]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can further characterize the lesion, defining its location and relationship to paratesticular structures. Sarcomas, except for liposarcomas, typically appear as solid, heterogeneous, and intensely enhancing masses on MRI. MRI can also assess local tumor extent, while CT of the abdomen and pelvis is the preferred modality for staging distant disease [13].

Due to diagnostic limitations, surgical intervention is typically necessary. Current treatment involves radical orchiectomy with wide local excision to mitigate the risk of local recurrence, particularly for high-grade tumors [6, 10]. This extensive approach aims to achieve clear surgical margins, as sarcomas often infiltrate surrounding tissues, making complete resection challenging [14]. If negative surgical margins cannot be achieved during the initial surgery, re-excision is imperative. Soft tissue reconstruction is often necessary after tumor excision when primary closure is not feasible. This approach promotes accelerated healing and rehabilitation [15, 16].

Due to limited evidence, the role of adjuvant therapies, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy, remains uncertain. However, these treatments may be considered for patients at high risk of local recurrence [10, 17].

Author contributions

K.A., A.A., and M.B. contribute equally to the data collection, paper writing, and revision.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Funding

None declared.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication is taken from the patient and will be submitted to the editor on demand.

References

Gatto L, Del Gaudio M, Ravaioli M, et al.

DeVita Jr VT, Rosenberg SA, Lawrence TS.