-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rebecca M. Rentea, Charles H. Fehring, Rectal colonic mural hematoma following enema for constipation while on therapeutic anticoagulation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 1, January 2017, rjx001, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx001

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Causes of colonic and recto-sigmoid hematomas are multifactorial. Patients can present with a combination of dropping hemoglobin, bowel obstruction and perforation. Computed tomography imaging can provide clues to a diagnosis of intramural hematoma. We present a case of rectal hematoma and a review of current management literature. A 72-year-old male on therapeutic anticoagulation for a pulmonary embolism, was administered an enema resulting in severe abdominal pain unresponsive to blood transfusion. A sigmoid colectomy with end colostomy was performed. Although rare, colonic and recto-sigmoid hematomas should be considered as a possible diagnosis for adults with abdominal pain on anticoagulant therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Older adults with abdominal pain have a six- to eight-fold increase in mortality compared to younger patients [1, 2]. Intramural colonic hematomas manifest rarely as complications following blunt traumas or accompanying diseases with bleeding tendency.

CASE REPORT

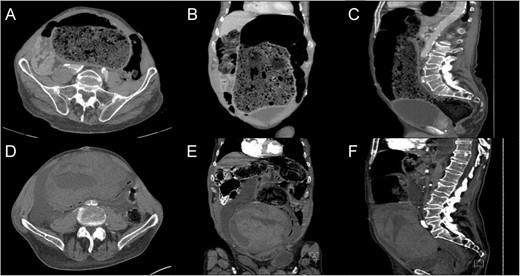

CT – Abdomen and Pelvis with intravenous contrast. Admission imaging demonstrating large colonic stool burden in the axial (A), coronal (B) and sagittal orientation (C). CT abdomen and pelvis following enema demonstrating large colonic wall hematoma axial (D), coronal (E) and sagittal orientation (F).

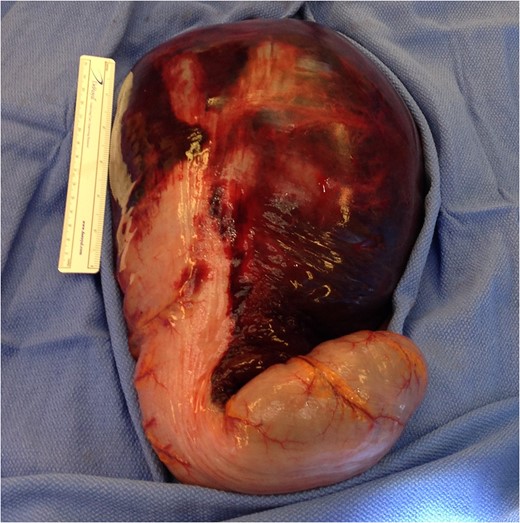

Intraoperative photograph of the large intramural hematoma of the sigmoid colon descending into the recto-sigmoid junction.

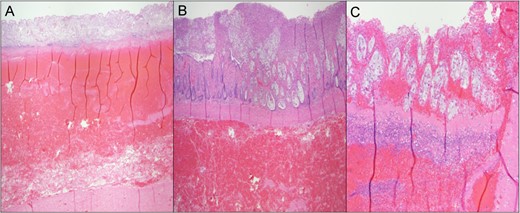

Pathologic colonic cross section. (A) Hemorrhagic infarction of the sigmoid colon. (B) Ischemic bowel with pseudomembrane formation. (C) Ischemic bowel with hemorrhage and pseudomembrane formation.

DISCUSSION

Intramural hematomas of the alimentary tract are uncommon, occurring most frequently in the setting of blunt abdominal trauma (duodenum most common, colon least common), and in 15–36% are spontaneous in patients with underlying hematologic disease or on anticoagulant therapy [3]. Large hematomas are usually found in the submucosal layer were microvascular structures reside [4].

Hemorrhagic complications while on therapeutic anticoagulation are well recognized. The incidence of all bleeding complications during anticoagulation therapy ranges from 5 of 48%, but gastrointestinal hemorrhage occurs in only 2 to 4% of patients [5]. Small bowel hematoma has an incidence of 1 case per 2500 anticoagulated patients per year, while large bowel hematomas have an even lower incidence in the literature [6]. Gastrointestinal complications following anticoagulation can present with bleeding into the intestinal lumen, usually related to some underlying mucosal abnormality [7], retroperitoneal hemorrhage or bleeding into intra-abdominal organs; less common are intramural hematomas.

Rectal hematoma and subsequent perforation have been described in patients following enemas and radiographic contrast enemas [8] due to both instrumentation and hydrostatic pressure [9]. One study demonstrated that the incidence of iatrogenic large bowel perforations ranges from 0.1 to 0.9% following colonoscopy and barium enemas. The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain for a patient on anticoagulation is broad including rectus sheath hematoma, retroperitoneal hematoma, intestinal/mesenteric hematoma, bleeding diverticula and rectal trauma from enema or foreign object.

The use of CT as the first imaging modality in the evaluation of patients with acute abdominal complaints especially in the elderly population [10]. CT characteristics of colonic hematoma include circumferential wall thickening, intramural hyper-density, luminal narrowing and intestinal obstruction. Additional adjuncts for diagnosis consist of rigid proctoscopy which demonstrate colonic intramural hematomas as round shaped, dark reddish submucosal masses often obstructing the luminal space.

For patients with intramural hematomas treatment decisions depend on the symptoms and clinical findings. Conservative management includes removing the anticoagulation therapy, correcting coagulopathy, intestinal decompression and avoiding oral intake while awaiting spontaneous resorption of the hematoma [11]. However only 30% of colonic hematomas respond to conservative management. The challenge is to distinguish patients with self-limiting intramural hematoma from those with more severe pathology. Conventional physical exam signs are inadequate to distinguish more ill patients as even a simple hematoma may also present with high fevers, leukocytosis and rebound tenderness.

If the intramural hematoma causes obstruction or if the cause of the bowel obstruction is unknown, surgical intervention for colonic hematoma is warranted. Drainage of the hematoma may increase the risk of serious infection as it introduces bacteria to a previously sterile hematoma.

A review of the literature demonstrates a shift in the management of colonic hematomas over the past 50 years. Cases prior to 1969 were most commonly treated with surgical intervention [12]. However, following 2010 they were managed more frequently conservatively [13].

Treatment of colonic hematomas depends on symptoms and clinical findings [11, 14]. Overall bowel obstruction in a patient on anticoagulation with acute abdominal pain results in operative exploration in 67% (42 of 51 patients). For those reasons we recommend laparotomy for those who fail to improve 24–36 hours [15]. Indications for immediate surgical intervention include active and persistent intra-abdominal bleeding, intestinal wall ischemia with or without bowel perforation and peritonitis [16]. Surgical treatment consists of bowel resection with primary anastomosis with or without diverting colostomy. Many case series and reports have demonstrated that patients with distal colonic hematomas required diverting colostomies 80% of the time [17].

Procedural alternatives to surgical intervention have been described in case reports and series. Endoscopic drainage requires colonic wall viability [18] but could result in relief of the ‘tamponade effect’ of the hematoma [19]. Selective mesenteric embolization can be performed in patients with an active blush into the colonic wall with an 85% success rate, and an overall 20% of complication as a result of the procedure.

Recto-sigmoid hematomas should be considered as a diagnosis for a patient with a dropping hemoglobin and abdominal pain in the setting of an enema on therapeutic anticoagulation. Characteristic clinical and imaging findings may aid in making a timely diagnosis. There is an increasing role for conservative management. If obvious signs of clinical deterioration such as free air and failure to respond to correction of coagulation are identified, then operative intervention should commence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Department of Surgery (Nicholas Meyer, M.D.) for operative assistance, the Department of Radiology (Robert Lyons, M.D.) imaging interpretation and the Department of Pathology (Joseph A. Novak, M.D.) for the histologic slides at Columbia St. Mary's Hospital in Milwaukee, WI.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.