-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Khalid N. Shehzad, Sherif Monib, Omer F. Ahmad, Amjid A. Riaz, Submucosal lipoma acting as a leading point for colo-colic intussusception in an adult, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 10, October 2013, rjt088, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjt088

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Intussusception in adults is a rare condition, in contrast to paediatric intussusception where the majority of cases are idiopathic, ∼90% of adult cases have identifiable aetiology. The clinical presentation is often non-specific abdominal pain. We report the case of a 49-year-old gentleman who presented to our emergency department with a 10-day history of colicky abdominal pain. Computed tomography imaging revealed a lipomatous mass lesion in the transverse colon leading to intussusception. An extended right hemicolectomy was performed with a good result. Histology confirmed that the leading point of the intussusception was a large submucosal lipoma. Gastrointestinal lipomas are rare and largely asymptomatic. However, they may cause abdominal pain, bleeding per rectum, obstruction or intussusception. Since adult colonic intussusception is frequently associated with malignant organic lesions, the differential diagnosis is important, and timely surgical intervention paramount.

INTRODUCTION

Adult intussusception is uncommon, accounting for ∼1–5% of intestinal obstructions in adults. We report a case of adult intussusception due to an underlying submucosal lipoma in the transverse colon.

CASE REPORT

A 49-year-old gentleman presented to our emergency department with a 10-day history of intermittent abdominal pain. The pain was exacerbated by eating and he reported a reduced appetite. His past medical history included a right-sided nephrectomy for a benign tumour and an appendicectomy.

On examination, he was apyrexial and vital signs were all within normal limits. Abdominal examination revealed a soft abdomen, with localized epigastric tenderness. There were no palpable masses and bowel sounds were normal. Laboratory blood tests were unremarkable, apart from a mild microcytic anaemia.

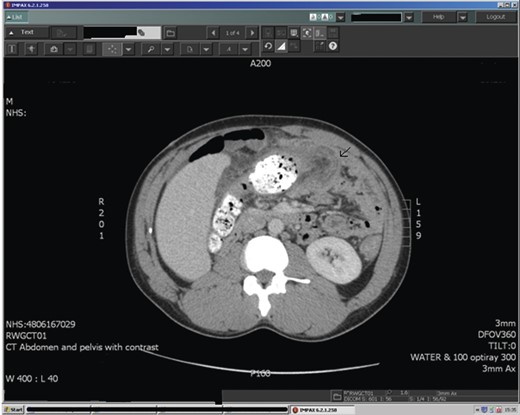

Abdominal ultrasound demonstrated a bowel-related mass lesion in the epigastric region (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 3 × 6 cm fatty ovoid lesion within the transverse colon resulting in intussusception (Fig. 2). Colonoscopy showed an abnormal dusky grey lesion occupying most of the lumen in the distal transverse colon. There were two ulcerated areas on the front of the lesion, most likely the leading point of the intussusception. A laparotomy was performed. Intussusception of the transverse colon was found, for which an extended right hemicolectomy was performed (Fig. 3), with ileo-transverse colon anastomosis and defunctioning loop ileostomy. The patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery and returned later for reversal of his loop ileostomy. The histopathology report confirmed a 6 × 4.5 cm submucosal lipoma acting as a leading point for the intussusception. There was no evidence of malignancy.

Ultrasound of the abdomen demonstrating a bowel related mass lesion in the epigastric region.

Intraoperative photograph showing the colonic lipoma in excised transverse colon.

DISCUSSION

Adult intussusception is a rare condition. Intussusceptions can be classified into four categories according to location: (i) enteric—confined to the small bowel, (ii) colonic—involvement of large bowel exclusively, (iii) ileocolic—prolapse of the ileum into the colon through the ileocaecal valve and (iv) ileocaecal—where the ileocaecal valve acts as the lead point, however it can be difficult to distinguish between the last two in clinical practice [1].

Childhood intussusception is idiopathic in the majority of cases and reduction is appropriate. Conversely, in adult intussusception, ∼90% of cases have identifiable aetiology acting as the lead point [2]. The majority of intussusceptions occurring in the small bowel are secondary to benign lesions, whilst colo-colonic cases are more likely to have a malignant aetiology, with adenocarcinoma and lymphoma being the most common lesions. Benign lesions account for only ∼30% of cases; responsible lesions include adenomatous polyp, lipoma, haemangioma, neurofibroma and leiomyoma [3].

Lipomas represent the second most common benign tumours found in the colon, with a reported incidence ranging between 0.035 and 4.4% [4]. The majority arise from the submucosa, but occasionally they originate from the subserosa. They tend to be isolated. However, in ∼10% of cases multiple lipomas occur, particularly when a lipoma is found in the caecum. They are most frequently located in the right hemi-colon [4]. The size of lipomas reported in the literature varies from 2 mm to 30 cm. Small lipomas tend to remain asymptomatic and are usually detected incidentally. Larger lipomas are more frequently symptomatic, those >4 cm are considered giant and produce symptoms in 75% of cases [5]. They can mimic symptoms of colonic malignancy and present in similar age groups. They may cause bleeding, obstruction or intussusception. The main symptom reported is chronic, colicky abdominal pain.

Adult intussusception has a non-specific presentation and is often not considered in the differential diagnosis for abdominal complaints. The classical paediatric triad of abdominal pain, bloody diarrhoea and a tender abdominal mass is rarely seen in adults. Abdominal pain, nausea, altered bowel habit and bleeding per rectum may be reported in adults, or the patient may present with features of acute bowel obstruction [6].

Abdominal CT is considered the most sensitive radiological method for diagnosis of intussusception, with characteristic features of a ‘target’ or ‘sausage’ shaped soft tissue mass with a layering effect [7]. Identification of a lead mass is often possible, although determining the underlying aetiology is difficult. On a CT scan, a lipoma manifests as a well-marginated spherical or ovoid mass, with fat attenuation.

Colonoscopy may allow direct visualization of the lipoma, which can appear as a yellow, smooth mass with pedunculated or sessile base. Characteristic endoscopic features include the ‘cushion sign’ (forcing the forceps against the lesion results in depression and then restoration of the mass) and ‘naked fat sign’ (fat extrusion during the biopsy) [8]. Smaller lipomas (<2 cm) may not require intervention if they are asymptomatic. Larger lipomas are more likely to be symptomatic and may require intervention. There is some evidence to suggest that endoscopic removal of larger lipomas (>2 cm) is associated with a greater risk of perforation [9]. Therefore, large symptomatic lipomas usually require surgical resection.

It is generally accepted that most cases of adult colonic intussusception will require surgical intervention, with en-bloc resection without reduction of the affected segment due to the high risk of underlying malignancy. Reduction before limited resection may be appropriate for cases of small bowel intussusception where a pre-operative diagnosis of benign aetiology can be confirmed [10].

In conclusion, adult bowel intussusception is a rare condition often posing a diagnostic challenge to the surgeon due to its non-specific presentation. A high index of suspicion and prompt investigations can aid diagnosis, with abdominal CT being the most sensitive imaging modality. Gastrointestinal lipomas are usually asymptomatic; however, they can cause bleeding, intussusception and obstruction. Since adult colonic intussusception is frequently associated with malignant organic lesions, being aware of the differential diagnosis is important and timely surgical intervention paramount.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were responsible for the ongoing care of the patient in hospital and conceived, researched and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.