-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

J Taylor, A Wojcik, Upper limb compartment syndrome secondary to streptococcus pyogenes (Group A streptococcus) infection, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 3, March 2011, Page 3, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.3.3

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Compartment syndrome caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A streptococcus) has rarely been described. We report a case of a healthy 44-year-old male who presented with compartment syndrome of the right forearm and subsequent acute respiratory distress syndrome. The patient received antibiotics and urgent surgical decompression, followed by delayed wound closure without the need for skin grafting. The patient recovered with no loss of power, sensation or range of movement. High index of suspicion, early intervention and excellent post-operative management were essential in recovery.

INTRODUCTION

Compartment syndrome is clinically defined as an increase in a tissue pressure within a closed anatomical space, which sufficiently reduces capillary perfusion to compromise the viability of the enclosed tissues (1). Acute compartment syndrome of the forearm has a wide variety of aetiologies. Relatively frequent causes include supracondylar humerus fractures in children and distal radius fractures in both paediatric and adult patients (2,3,4). Other causes range from snakebites, to malfunctioning tourniquets, and rarely a complication of infection (5,6,7,8). We report a case of compartment syndrome of the forearm resulting from a minor skin abrasion and subsequent Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A) infection.

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old gentleman presented to the emergency department one week after falling onto his right elbow, obtaining a minor graze. The elbow had become swollen and erythematous. Olecranon bursitis was diagnosed and the bursa was incised and drained. The patient was sent home on oral antibiotics.

Two days later, the patient returned to hospital with rigors, pyrexia, and greatly increased distribution of erythema and tumor. In addition, the patient had a decreased range of movement of the elbow and wrist joints, which was very painful. The initial differential included cellulitis and septic arthritis, and intravenous flucloxacillin and benzyl penicillin were initiated. Blood results included a raised C-reactive-protein and white blood count. The following morning the patient had further deteriorated. The SHO noted that passive extension of the fingers of the right hand produced pain out of proportion to the clinical setting and that fingers were showing signs of pallor and paraesthesia. The consultant reviewed the patient and placed him on the emergency list for a myofascial release pending any further decline in clinical condition.

As the day progressed, the patient experienced worsening pain and he was taken to theatre. Three incisions (Figures 1 and 2) were made on the forearm – one over the olecranon, one on the volar aspect of the forearm and the third over the dorsal aspect. The operative findings included grossly oedematous, constricting subcutaneous tissues throughout the forearm, and notably an area of necrotic tissue in the region of the olecranon bursa. All of the four fascial compartments of the forearm were opened. The wounds were left open and covered in a loose dressing and bandages, with the arm elevated in a Bradford sling.

Following discussion with the microbiologists, who by this time had the results of the initial join aspirate (Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A) and moderate growth Staphylococcus aureus), a change of antibiotics to Tazocin and clindamycin was recommended, with the advice to add vancomycin if the patient deteriorated. The following morning, the patient had improved clinically, with reduced pain, paraesthesia, pallor and pain on passive extension of the fingers. In the evening, the patient rapidly began to decline. At 4pm, saturations on air dropped to 88% and the patient developed a dry cough. This was initially thought to be secondary to opiate toxicity, however two hours later the saturations on 50% oxygen decreased to 66%. An ABG performed at the time showed a H+ of 41.3, pCO2 of 5.0, pO2 of 5.2, Lactate of 2.0 and base excess of -2.8. Additionally, the patient became pyrexial, with a temperature of 39.3 degrees centigrade. An urgent transfer to the hospital intensive care unit (ICU) was organised.

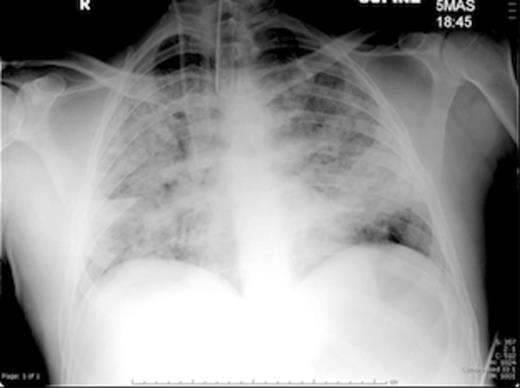

The patient was rapidly intubated and ventilated on ICU. A chest x-ray highlighted bilateral extensive acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Figure 3). He continued to receive intravenous antibiotics, ionotropic support and nasogastric feeding. The orthopaedic team reviewed the patient daily and dressings were changed regularly.

Eleven days following the initial fasciotomy, the wounds were closed successfully – no skin grafting was required. The patient was extubated four days later, antibiotics were stopped the following day, and he was discharged to the ward after nineteen days on ICU. Intensive physiotherapy, nutritional and psychological support was administered and the patient was discharged home twenty-seven days after being admitted.

A clinic follow up with the plastic surgeons revealed excellent healing of all wounds, excluding a small wound over the olecranon. This was subsequently managed conservatively with dressings. Most importantly, the patient recovered with full range of motion, power and sensation of the right arm.

DISCUSSION

Forearm compartment syndrome is often diagnosed clinically. The signs associated with compartment syndrome have traditionally been referred to as the ‘Five ‘P’s’’, namely pain, pallor, paraesthesia, pulselessness and pain with passive stretch of muscles (9). Pulselessness is regarded as a late finding and does not always accompany compartment syndrome.

Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A streptococcus) is a Gram-positive, non-motile, non-spore-forming coccus that occurs in chains or in pairs of cells. It is one of the most frequent human pathogens, with estimations existing that between 5-15% of individuals carry the bacterium without signs of disease. Streptococcal infection has been reported as a cause of compartment syndrome in a handful of other cases (8), with end results ranging from wound closure by skin grafting to amputation through the elbow. This suggests that the keen clinical suspicion and early action taken in this case report have produced an excellent result. Administration of both oral and intravenous antibiotics at an early stage in this case did not prevent the progression to compartment syndrome, which is why close monitoring and regular examinations are essential to make the diagnosis.