-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

R Ramirez-Maldonado, E Ramos, J Dominguez, R Mast, L Llado, J Torras, J Hernandez, Pseudoaneurysm of the right hepatic artery and bile duct necrosis as a complication of acute cholecystitis in a diabetic patient, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 3, March 2011, Page 4, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.3.4

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A very uncommon complication of acute cholecystitis is the development of a pseudoaneurysm in an arterial branch of the hepatic artery. We report a rare case of a patient with acute cholecystitis who presented with a pseudoaneurysm of the right anterior hepatic artery complicated by necrosis of the bile duct and hepatic infarction. A 70-year-old woman attended the emergency department with an unusual presentation of acute cholecystitis involving abdominal discomfort and a mass in the right upper quadrant. CT demonstrated a pseudoaneurysm of the right hepatic artery. Emergency selective transcatheter arterial embolization and cholecystectomy were performed. Subsequently, bile duct necrosis and hepatic ischemic damage made it necessary to perform a right hepatectomy and bile duct resection. Once a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm is confirmed, its embolization may be useful to ensure the patient’s safety. However, in our experience such pseudoaneurysms may be associated with hepatic and biliary ischemia.

INTRODUCTION

A very uncommon complication of acute cholecystitis is the development of pseudoaneurysms in the arterial branches of the hepatic artery. We report a very rare case of a patient with perforated acute cholecystitis who presented a pseudoaneurysm of the right anterior hepatic artery associated with necrosis of the bile duct and liver infarctions.

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old diabetic woman was seen in the emergency department with abdominal pain of two weeks duration, without fever. At the time of admission her general condition was good, although she reported abdominal discomfort and there was a hard mass in the epigastrium. Laboratory test results indicated mild cholestasis: bilirubin 147 umol/l (normal values <18), alkaline phosphatase 7.4 ukat/l (normal <1.5), glutamyltransferase 8.39 ukat/l (normal <0.5), haematocrit 40% and white blood cell (WBC) count of 14 800. Her coagulation test results were within normal limits.

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed intrahepatic dilatation of the biliary tree and a heterogeneous mass at the gallbladder fossa. The gallbladder was poorly defined, with loss of definition of the contours and stones inside. The initial radiological diagnosis was a gallbladder tumour.

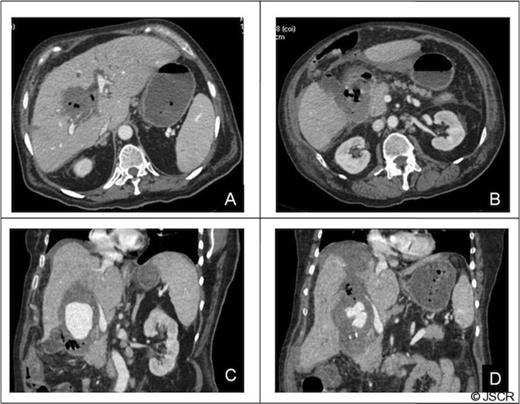

Forty-eight hours after admission the patient had an episode of haemodynamic instability suggestive of septic shock, which was also associated with a drop of 15 points in haematocrit levels (haematocrit: 24, WBC: 33 000). Empirical antibiotic therapy was begun and abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was performed. CT showed a pseudoaneurysm of the right hepatic artery (RHA) of 7 cm in diameter, haemoperitoneum, intrahepatic dilatation of the biliary tree bile duct and the presence of hepatic infarction, and duodenal wall involvement (Figures 1 and 2).

CT of the abdomen: A) Tridimensional reconstruction, B) Axial slice C) Coronal slice (a;.Pseudoaneurysm of the right anterior hepatic artery, b;Left hepatic artery, c;Common hepatic artery, d;Gastroduodenal artery). The right posterior hepatic artery arises from the left hepatic artery.

CT of the abdomen: Complications of the pseudoaneurysm A, B) Hepatic infarction C)Duodenal wall involvement, D) Hemoperitoneum under right hemidiaphragm.

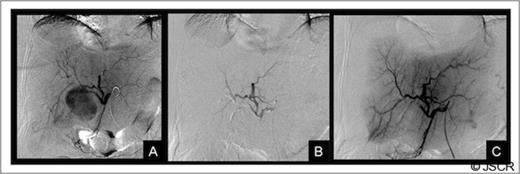

Given these findings an arteriography was performed confirming pseudoaneurysm of the right anterior hepatic artery. The patient then underwent embolization and occlusion of the RHA with coils and an Amplatzer Vascular Plug (AGA Medical, Golden Valley, MN) (Figure 3).

Liver arteriography: A) Selective arteriography of the common hepatic artery showing a pseudoaneurysm of the right anterior hepatic artery, B and C) Result after embolization with coils and an Amplatzer vascular plug. The figure shows a complete occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm and the right anterior hepatic artery.

Eight hours after this procedure the patient’s condition worsened again and surgery was required. During the operation, the presence of a cholecystoduodenal fistula was confirmed, and signs of bile duct ischemia were found. Consequently, a cholecystectomy, debridement and drain placement were performed.

Twenty-eight days after admission the patient had another sepsis episode. A new abdominal CT showed an increase in the size of hepatic infarctions in the right liver, and puncture of the infarcted area revealed purulent material. Culture was positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis. Given the lack of resolution of sepsis, it was decided to perform surgical revision. During this second operation, extensive hepatic necrosis of the right hepatic bile duct was observed at the main junction. The patient therefore underwent right hepatectomy with resection of the necrotic bile duct, hepaticojejunostomy and duodenal exclusion. She subsequently required hospitalization for 9 months due to various infectious abdominal and respiratory complications. However, she was eventually discharged and currently presents an almost complete recovery of normal activity.

DISCUSSION

Aneurysms of the hepatic artery and its branches are rare and are mostly related to local inflammation and sepsis. Although cholecystitis is the most common cause of cystic artery aneurysms (1,2,3,4,5,6,7) a review published in 2007(3) identified only 15 cases with this complication. The association with RHA pseudoaneurysm is even rarer and, as far as we know, only two cases have previously been reported (8,9).

Pseudoaneurysm of the RHA is very rare and is most commonly associated with previous gallbladder surgery. The formation of pseudoaneurysms in patients with cholecystitis has no clear explanation. It can be speculated that after perforation of the gallbladder, the inflammatory process damages the adventitia of a nearby arterial branch, causing thrombosis of the vasa vasorum which, in turn, leads to weakness and eventual rupture of the wall. The low frequency of this complication, despite the high incidence of acute cholecystitis, may be due to early thrombosis of the cystic artery in the context of severe acute cholecystitis (4). One possibility is that the retention of a large stone in the cystic duct facilitates the formation of the pseudoaneurysm.

In 56% of cases (3), rupture of the cystic artery pseudoaneurysm occurs at the vesicular lumen, which clinically presents as upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to haemobilia. Therefore, the appearance of the classic triad of haemobilia (abdominal pain, jaundice and upper gastrointestinal bleeding) in the context of a patient with symptoms of cholecystitis should suggest the possibility of an arterial pseudoaneurysm at the hepatic pedicle. The first reported case of hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm in a patient with cholecystitis(9) also presented as haemobilia. In the second patient (8) there was also a rupture of the pseudoaneurysm in the vesicular lumen, but without gastrointestinal bleeding. Although in many cases the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm may be suspected on ultrasound, which did not occur in our patient, confirmation requires a CT scan with contrast injection.

Given the rarity of the hepatic pedicle pseudoaneurysm associated with cholecystitis, there is insufficient evidence to recommend a specific therapeutic strategy. However, when diagnosis has been possible before surgery, pseudoaneurysm embolization is indicated in order to control bleeding. Biliary surgery can be deferred in patients with a poor general condition, while minimizing the risk of bleeding during cholecystectomy. This strategy of arterial embolization followed by elective cholecystectomy seems more reasonable when the pseudoaneurysm is of the right hepatic artery, because in this situation the technical difficulties are even greater (7). However, arterial embolization does carry a higher risk of ischemic complications when the pseudoaneurysm affects the RHA.

In the case of our patient there were already signs of ischemia to the liver and bile duct, which was probably aggravated by arterial embolization. It may be that the intense local inflammatory process favoured the small-vessel arterial thrombosis, and the haemodynamic instability associated with the disease may have prevented the formation of adequate collateral circulation.

In summary, pseudoaneurysm of the RHA is an exceptional and serious complication of perforated cholecystitis. Treatment requires the use of interventional radiology and, in our experience, these pseudoaneurysms may be associated with liver and biliary ischemia.