-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hamza Abdulkarim Nasif, Omar H Salloum, Sundus Imran Al-Atrash, Taha Z Makhlouf, Orwa Al-Fallah, Rafiq Salhab, Type IV appendiceal intussusception with mucocele and acute appendicitis: a rare case and diagnostic challenge, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf282, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf282

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Appendiceal intussusception is an exceedingly rare condition where a segment of the appendix invaginates into itself or the cecum. We present a case of a 22-year-old female without significant medical history who presented to the emergency room with acute abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever for 7 hours. Clinical examination revealed diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding, with stable vitals. Laboratory results showed leukocytosis and elevated C-reactive protein. Abdominal ultrasound and a limited non-contrast computed tomography scan, suggested ileocecal intussusception, but the appendix was not visualized, indicating it as the leading point. Intraoperatively, an inflamed appendix with mucocele and a Type IV intussusception, where the appendix telescoped into itself and the cecum, was found. Manual reduction, appendectomy, and partial cecectomy were performed. Histopathology confirmed severe appendiceal inflammation but no malignancy. This case highlights the diagnostic challenges and rarity of Type IV appendiceal intussusception, emphasizing the importance of surgical exploration in complex presentations.

Introduction

Appendiceal intussusception (AI) is a pathological condition in which a portion of the appendix invaginates into its own lumen or into the cecum [1]. The incidence of AIs is 0.01%, making them extremely rare [2]. In adults, females are more commonly affected, in contrast to pediatrics where the incidence in males is higher [3]. The leading cause in adults is endometriosis, followed by appendiceal inflammation and mucocele [4]. Other causes include tumorous and carcinoid tumors, metastases, hamartomas, and lymphomas [4]. The clinical manifestations are quite varied, ranging from asymptomatic cases to acute, severe pain in the right iliac fossa that mimics acute appendicitis to episodic, persistent symptoms including pain, vomiting, or rectal bleeding [3, 4]. Ultrasonography is a crucial diagnostic tool when diagnosing pediatric AIs. Computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography can be used for preoperative diagnosis in adults, although these methods are exceedingly challenging, and many cases are detected during or after surgery [5], from a simple appendectomy to a right hemicolectomy, is the only effective therapy for appendicular intussusception [6].

Case presentation

A 22-year-old female with no notable past medical or surgical history came to the emergency room with acute abdominal pain lasting for 7 hours. The pain started suddenly in the periumbilical region, was crampy, progressively worsened, and eventually spread throughout her abdomen. She also experienced nausea, vomiting, and fever.

On examination, the patient looked in pain, cramping in bed, but fully conscious and alert, and hemodynamically stable (heart rate was 90 bpm, blood pressure 120/80 mmHg, SpO2 97%, respiratory rate was 16), palpation of abdomen revealed diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding, but with no palpable masses, and hernial orifices were intact.

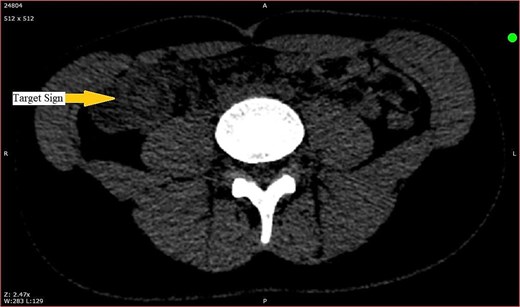

Further laboratory investigations including complete blood count revealed leukocytosis as white blood cells count of 16.4 × 109/l, with neutrophilic predominance, and mildly elevated C-reactive protein of 9.3 mg/l, abdominal ultrasound showed a target sign with dilated thickened appendiceal and cecal wall. A limited noncontrast abdominal CT scan was carried out to localize appendix, that showed a target sign in right iliac fossa, measuring 3 × 3.5 cm, suggesting ileocecal intussusception (Fig. 1), appendix was not visualized, suggesting the possibility of being a leading point in intussusception.

CT scan showing target sign in the right iliac fossa, suggestive of ileocecal intussusception.

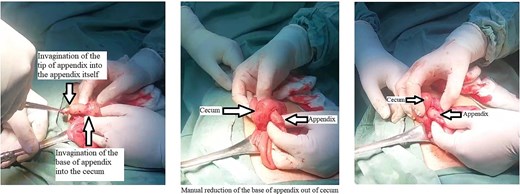

Patient underwent open surgery, which revealed an inflamed appendix with mucocele, with a distal retrograde intussusception of the tip into the appendix itself, and invagination of the base into the cecum, manual reduction was done (Fig. 2), with appendectomy and wedged (partial) cecectomy. Excised appendix measured 6 × 2 × 1 cm. Pathology study mentioned an external surface of the appendix covered with exudate, a severely inflamed appendix with serositis, and acute inflammation of the cecal wall, but negative for malignancy.

The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged 4 days post-surgery. At the 2-week follow-up, the wound had healed well, and the patient was symptom-free with no new complaints. They were advised to continue with routine check-ups.

Discussion

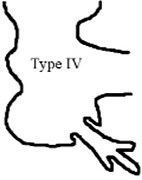

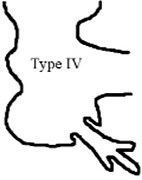

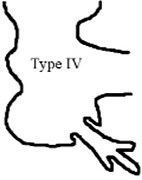

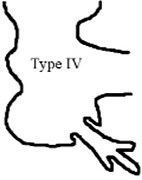

AI is considered a rare condition [2]. It was initially documented by McKidd in 1858 and later classified by McSwain in 1941, Fink in 1964 (Table 1), and Atkinson in 1976 [7, 8]. In our case, the AI was classified as Type IV, where the proximal portion of the appendix intruded into its distal portion. This classification was confirmed through imaging studies, which revealed the unique presentation of the appendix partially invaginated into the cecum. Type IV AI is particularly rare and presents a diagnostic challenge due to its atypical presentation, making this case noteworthy in the context of the broader literature on AI.

| Type . | Description . | Illustration . | Incidence . |

|---|---|---|---|

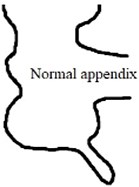

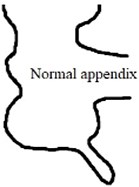

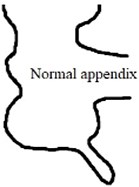

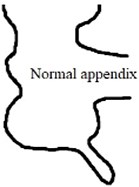

| Normal appendix | Normal anatomical position of appendix |  | |

| Type I | The tip of the appendix folds inward into itself (inversion) |  | 3% |

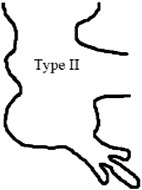

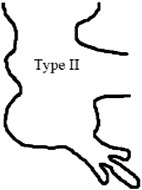

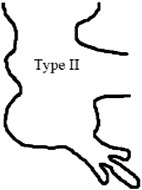

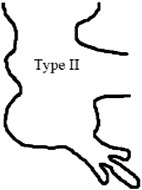

| Type II | The tip of the appendix intrudes into itself without inverting |  | 35% |

| Type III | The proximal portion of the appendix intrudes into the cecum |  | 1% |

| Type IV | The proximal portion of the appendix intrudes into its distal portion |  | 21% |

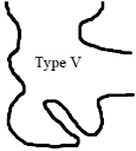

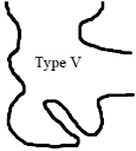

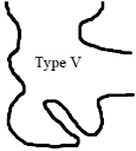

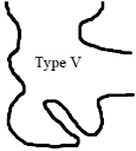

| Type V | The entire appendix inverts and is pulled into the cecum |  | 40% |

| Type . | Description . | Illustration . | Incidence . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal appendix | Normal anatomical position of appendix |  | |

| Type I | The tip of the appendix folds inward into itself (inversion) |  | 3% |

| Type II | The tip of the appendix intrudes into itself without inverting |  | 35% |

| Type III | The proximal portion of the appendix intrudes into the cecum |  | 1% |

| Type IV | The proximal portion of the appendix intrudes into its distal portion |  | 21% |

| Type V | The entire appendix inverts and is pulled into the cecum |  | 40% |

| Type . | Description . | Illustration . | Incidence . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal appendix | Normal anatomical position of appendix |  | |

| Type I | The tip of the appendix folds inward into itself (inversion) |  | 3% |

| Type II | The tip of the appendix intrudes into itself without inverting |  | 35% |

| Type III | The proximal portion of the appendix intrudes into the cecum |  | 1% |

| Type IV | The proximal portion of the appendix intrudes into its distal portion |  | 21% |

| Type V | The entire appendix inverts and is pulled into the cecum |  | 40% |

| Type . | Description . | Illustration . | Incidence . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal appendix | Normal anatomical position of appendix |  | |

| Type I | The tip of the appendix folds inward into itself (inversion) |  | 3% |

| Type II | The tip of the appendix intrudes into itself without inverting |  | 35% |

| Type III | The proximal portion of the appendix intrudes into the cecum |  | 1% |

| Type IV | The proximal portion of the appendix intrudes into its distal portion |  | 21% |

| Type V | The entire appendix inverts and is pulled into the cecum |  | 40% |

AI has numerous underlying causes. The most common cause of AI in children is appendiceal inflammation [9]. AI can result from abnormal peristalsis. Other causes of AI included endometriosis, lymphoma, adenoma, hyperplasia, mucocele, torsion, and pregnancy, foreign body, lymphoid hyperplasia, parasites, polyps, and mucinous cystadenoma [1, 7].

AI is diagnosed via ultrasonography, CT, contrast enema, and colonoscopy. Accurate diagnosis of appendiceal intussusception involves differentiating it from other conditions with similar presentations. Table 2 summarizes the differential diagnoses considered in this case, including their key features and how they were excluded based on the patient’s clinical and imaging findings.

| Differential diagnosis . | Key features . | Rationale for inclusion . | How it was excluded . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute appendicitis | Periumbilical pain that migrates to the right lower quadrant, nausea, vomiting, fever | Classic presentation, but complicated by intussusception in this case | Confirmed by imaging (CT scan) showing AI and inflammation |

| Gastroenteritis | Diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever | Common cause of abdominal pain, especially in young adults | Lack of diarrhea and more localized pain, imaging findings consistent with appendicitis |

| Acute mesenteric ischemia | Sudden onset of severe abdominal pain, out of proportion to physical findings | Considered in severe, acute abdominal pain with vascular risk factors | Normal vascular imaging, lack of significant risk factors, and absence of ischemic signs |

| Intussusception | Intermittent crampy abdominal pain, vomiting, possible “currant jelly” stools | Rare in adults, particularly with appendiceal involvement | Confirmed as part of the diagnosis with AI on CT scan |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Lower abdominal pain, fever, vaginal discharge, pain during intercourse | Common in sexually active females, considered with lower abdominal pain and fever | No history of sexual activity, no vaginal discharge, or pain during intercourse |

| Ovarian torsion | Sudden onset of unilateral pelvic pain, nausea, vomiting, adnexal tenderness | Gynecological emergency in women of reproductive age, considered with acute pelvic/abdominal pain | Normal pelvic ultrasound, absence of adnexal mass, or torsion on imaging |

| Ectopic pregnancy | Unilateral pelvic pain, missed periods, vaginal bleeding, positive pregnancy test | Important to rule out in any woman of childbearing age presenting with acute abdominal/pelvic pain | Negative pregnancy test, absence of gynecological symptoms |

| Renal colic (ureteral stone) | Flank pain radiating to groin, hematuria, nausea, vomiting | Severe, colicky pain often with a history of kidney stones can mimic acute abdomen | No hematuria, pain not localized to flank, or radiating to groin, normal renal ultrasound |

| Peptic ulcer disease with perforation | Sudden, severe epigastric pain, signs of peritonitis, history of NSAID use, or Helicobacter pylori infection | Perforation leads to an acute abdomen with diffuse pain and signs of peritoneal irritation | Lack of epigastric pain, no history of NSAID use, normal upper GI endoscopy |

| Acute cholecystitis | Right upper quadrant pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, Murphy’s sign positive | Right upper quadrant pain with fever and leukocytosis, typically radiates to the right shoulder or back, important differential diagnosis to rule out | No right upper quadrant pain, negative Murphy’s sign, normal gallbladder on ultrasound |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, rectal bleeding | Considered with a history of chronic symptoms, but can present with acute flare-ups | No history of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, normal colonoscopy, and biopsy |

| Differential diagnosis . | Key features . | Rationale for inclusion . | How it was excluded . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute appendicitis | Periumbilical pain that migrates to the right lower quadrant, nausea, vomiting, fever | Classic presentation, but complicated by intussusception in this case | Confirmed by imaging (CT scan) showing AI and inflammation |

| Gastroenteritis | Diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever | Common cause of abdominal pain, especially in young adults | Lack of diarrhea and more localized pain, imaging findings consistent with appendicitis |

| Acute mesenteric ischemia | Sudden onset of severe abdominal pain, out of proportion to physical findings | Considered in severe, acute abdominal pain with vascular risk factors | Normal vascular imaging, lack of significant risk factors, and absence of ischemic signs |

| Intussusception | Intermittent crampy abdominal pain, vomiting, possible “currant jelly” stools | Rare in adults, particularly with appendiceal involvement | Confirmed as part of the diagnosis with AI on CT scan |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Lower abdominal pain, fever, vaginal discharge, pain during intercourse | Common in sexually active females, considered with lower abdominal pain and fever | No history of sexual activity, no vaginal discharge, or pain during intercourse |

| Ovarian torsion | Sudden onset of unilateral pelvic pain, nausea, vomiting, adnexal tenderness | Gynecological emergency in women of reproductive age, considered with acute pelvic/abdominal pain | Normal pelvic ultrasound, absence of adnexal mass, or torsion on imaging |

| Ectopic pregnancy | Unilateral pelvic pain, missed periods, vaginal bleeding, positive pregnancy test | Important to rule out in any woman of childbearing age presenting with acute abdominal/pelvic pain | Negative pregnancy test, absence of gynecological symptoms |

| Renal colic (ureteral stone) | Flank pain radiating to groin, hematuria, nausea, vomiting | Severe, colicky pain often with a history of kidney stones can mimic acute abdomen | No hematuria, pain not localized to flank, or radiating to groin, normal renal ultrasound |

| Peptic ulcer disease with perforation | Sudden, severe epigastric pain, signs of peritonitis, history of NSAID use, or Helicobacter pylori infection | Perforation leads to an acute abdomen with diffuse pain and signs of peritoneal irritation | Lack of epigastric pain, no history of NSAID use, normal upper GI endoscopy |

| Acute cholecystitis | Right upper quadrant pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, Murphy’s sign positive | Right upper quadrant pain with fever and leukocytosis, typically radiates to the right shoulder or back, important differential diagnosis to rule out | No right upper quadrant pain, negative Murphy’s sign, normal gallbladder on ultrasound |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, rectal bleeding | Considered with a history of chronic symptoms, but can present with acute flare-ups | No history of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, normal colonoscopy, and biopsy |

| Differential diagnosis . | Key features . | Rationale for inclusion . | How it was excluded . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute appendicitis | Periumbilical pain that migrates to the right lower quadrant, nausea, vomiting, fever | Classic presentation, but complicated by intussusception in this case | Confirmed by imaging (CT scan) showing AI and inflammation |

| Gastroenteritis | Diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever | Common cause of abdominal pain, especially in young adults | Lack of diarrhea and more localized pain, imaging findings consistent with appendicitis |

| Acute mesenteric ischemia | Sudden onset of severe abdominal pain, out of proportion to physical findings | Considered in severe, acute abdominal pain with vascular risk factors | Normal vascular imaging, lack of significant risk factors, and absence of ischemic signs |

| Intussusception | Intermittent crampy abdominal pain, vomiting, possible “currant jelly” stools | Rare in adults, particularly with appendiceal involvement | Confirmed as part of the diagnosis with AI on CT scan |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Lower abdominal pain, fever, vaginal discharge, pain during intercourse | Common in sexually active females, considered with lower abdominal pain and fever | No history of sexual activity, no vaginal discharge, or pain during intercourse |

| Ovarian torsion | Sudden onset of unilateral pelvic pain, nausea, vomiting, adnexal tenderness | Gynecological emergency in women of reproductive age, considered with acute pelvic/abdominal pain | Normal pelvic ultrasound, absence of adnexal mass, or torsion on imaging |

| Ectopic pregnancy | Unilateral pelvic pain, missed periods, vaginal bleeding, positive pregnancy test | Important to rule out in any woman of childbearing age presenting with acute abdominal/pelvic pain | Negative pregnancy test, absence of gynecological symptoms |

| Renal colic (ureteral stone) | Flank pain radiating to groin, hematuria, nausea, vomiting | Severe, colicky pain often with a history of kidney stones can mimic acute abdomen | No hematuria, pain not localized to flank, or radiating to groin, normal renal ultrasound |

| Peptic ulcer disease with perforation | Sudden, severe epigastric pain, signs of peritonitis, history of NSAID use, or Helicobacter pylori infection | Perforation leads to an acute abdomen with diffuse pain and signs of peritoneal irritation | Lack of epigastric pain, no history of NSAID use, normal upper GI endoscopy |

| Acute cholecystitis | Right upper quadrant pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, Murphy’s sign positive | Right upper quadrant pain with fever and leukocytosis, typically radiates to the right shoulder or back, important differential diagnosis to rule out | No right upper quadrant pain, negative Murphy’s sign, normal gallbladder on ultrasound |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, rectal bleeding | Considered with a history of chronic symptoms, but can present with acute flare-ups | No history of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, normal colonoscopy, and biopsy |

| Differential diagnosis . | Key features . | Rationale for inclusion . | How it was excluded . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute appendicitis | Periumbilical pain that migrates to the right lower quadrant, nausea, vomiting, fever | Classic presentation, but complicated by intussusception in this case | Confirmed by imaging (CT scan) showing AI and inflammation |

| Gastroenteritis | Diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever | Common cause of abdominal pain, especially in young adults | Lack of diarrhea and more localized pain, imaging findings consistent with appendicitis |

| Acute mesenteric ischemia | Sudden onset of severe abdominal pain, out of proportion to physical findings | Considered in severe, acute abdominal pain with vascular risk factors | Normal vascular imaging, lack of significant risk factors, and absence of ischemic signs |

| Intussusception | Intermittent crampy abdominal pain, vomiting, possible “currant jelly” stools | Rare in adults, particularly with appendiceal involvement | Confirmed as part of the diagnosis with AI on CT scan |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Lower abdominal pain, fever, vaginal discharge, pain during intercourse | Common in sexually active females, considered with lower abdominal pain and fever | No history of sexual activity, no vaginal discharge, or pain during intercourse |

| Ovarian torsion | Sudden onset of unilateral pelvic pain, nausea, vomiting, adnexal tenderness | Gynecological emergency in women of reproductive age, considered with acute pelvic/abdominal pain | Normal pelvic ultrasound, absence of adnexal mass, or torsion on imaging |

| Ectopic pregnancy | Unilateral pelvic pain, missed periods, vaginal bleeding, positive pregnancy test | Important to rule out in any woman of childbearing age presenting with acute abdominal/pelvic pain | Negative pregnancy test, absence of gynecological symptoms |

| Renal colic (ureteral stone) | Flank pain radiating to groin, hematuria, nausea, vomiting | Severe, colicky pain often with a history of kidney stones can mimic acute abdomen | No hematuria, pain not localized to flank, or radiating to groin, normal renal ultrasound |

| Peptic ulcer disease with perforation | Sudden, severe epigastric pain, signs of peritonitis, history of NSAID use, or Helicobacter pylori infection | Perforation leads to an acute abdomen with diffuse pain and signs of peritoneal irritation | Lack of epigastric pain, no history of NSAID use, normal upper GI endoscopy |

| Acute cholecystitis | Right upper quadrant pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, Murphy’s sign positive | Right upper quadrant pain with fever and leukocytosis, typically radiates to the right shoulder or back, important differential diagnosis to rule out | No right upper quadrant pain, negative Murphy’s sign, normal gallbladder on ultrasound |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, rectal bleeding | Considered with a history of chronic symptoms, but can present with acute flare-ups | No history of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, normal colonoscopy, and biopsy |

During the surgical exploration, the diagnosis of AI was confirmed. Despite initial imaging suggesting an ileocecal intussusception with an unvisualized appendix, the intraoperative findings revealed a rare Type IV AI. The appendix was observed to have telescoped into itself and partially invaginated into the cecum, forming a mucocele at the distal end. This unexpected discovery during surgery underscored the complexity of the case, highlighting the limitations of preoperative imaging and the critical role of surgical exploration in accurately diagnosing and managing such rare conditions.

Although few cases of ileocecal intussusception and appendicitis are documented in the literature, the combination of Type IV AI with concurrent acute appendicitis is exceptionally rare and has not been previously reported.

Initially, the clinical and imaging findings led us to suspect acute appendicitis, with the common presentation of appendiceal inflammation and a standard form of intussusception. The symptoms and diagnostic results aligned with typical appendicitis, and we anticipated a straightforward appendectomy.

However, intraoperatively, we discovered a more complex condition: an AI with a mucocele. The intussusception, identified as type IV, involved the appendix telescoping into itself and invaginating into the cecum, a rare presentation not anticipated in the preoperative diagnosis.

Histopathological examination confirmed the presence of severe inflammation and appendicitis, validating the initial suspicion of appendicitis but revealing the additional rare complication of intussusception.

This unexpected finding underscores the importance of a comprehensive surgical assessment when initial diagnoses are based on typical presentations.

In this case, the leading point of the intussusception was likely the mucocele of the appendix. Mucoceles are known to cause structural changes that can serve as a leading point for intussusception. The presence of the mucocele, combined with the severe inflammation of the appendix, created an ideal scenario for the appendix to telescope into itself and the cecum, leading to the Type IV AI observed during surgery. The mucocele’s abnormal growth and the resulting distortion of the appendix’s anatomy made it the primary contributor to the intussusception in this patient.

In managing AI, the choice of surgical and operative methods depends on the type of intussusception and whether the underlying condition is malignant or benign [10]. Accurate preoperative diagnosis is crucial for selecting the appropriate treatment. Radiologic studies play a key role in diagnosis: barium enema may show a “coiled-spring” or “spiral shell” appearance with an empty appendix, while air-contrast enema may reveal a “finger-like projection” outlined by air [11]. CT scans provide detailed anatomical information, often showing a target or sausage-shaped appearance of the intussusception. Colonoscopy may identify a mushroom or polypoid lesion in the cecum. Although sonography is used, it is less detailed for characterizing and differentiating AI [1]. In this case, since our patient declined an enema, we relied on the CT scan and surgical exploration, which became essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusion

This case highlights a rare Type IV AI with appendicitis and mucocele, emphasizing the diagnostic challenges and the need for open surgical exploration when preoperative diagnosis is uncertain. The combination of AI with acute appendicitis is exceptionally rare and underscores the importance of thorough surgical assessment in managing complex presentations.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the patient and their family for their great contribution. Also the authors express profound gratitude to the Polytechnic Medical Students’ Research Association (PMRA) for their invaluable contributions and unwavering support that significantly enriched every stage of the research journey.

Author contributions

Taha Z. Makhlouf, Omar H. Salloum, Hamza Abdulkarim Nasif, and Sundus Imran Al-Atrash (Concept and design), Taha Z. Makhlouf, Omar H. Salloum, Hamza Abdulkarim Nasif, and Sundus Imran Al-Atrash (Drafting of the manuscript), Taha Z. Makhlouf, Omar H. Salloum, Hamza Abdulkarim Nasif, and Sundus Imran Al-Atrash (Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content), Orwa Al-Fallah, Hamza Abdulkarim Nasif (Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data), and Rafiq Salhab (Supervision). All authors, Taha Z. Makhlouf, Omar H. Salloum, Hamza Abdulkarim Nasif, Sundus Imran Al-Atrash, Orwa Al-Fallah, and Rafiq Salhab, have reviewed the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that no conflict of interest could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data is available on request from the authors.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal if requested.