-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jamal Jawad, Rawan Mandura, Hatem Alhatem, Neurilemmoma of fronto-ethmoid paranasal sinuses: aggressive anterior skull base destructing tumor—a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 12, December 2020, rjaa469, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa469

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Neurilemmomas (Schwannomas) of sinonasal tract are very unusual. They are benign, slow-growing, usually solitary encapsulated perineural tumors. They arise from Schwann cells of the neural sheath of the peripheral nervous system including motor, sensory and autonomic nerves. They can occur throughout the body, but the head and neck region demonstrate a higher incidence of occurrence (25–45%). The sinonasal region, however, has the lowest incidence rate with only 3–4%. We report here a rare case of fronto-ethmoid sinus neurilemmoma that is locally destructing the anterior skull base and the lateral orbital wall. A left eye proptosis, diplopia and chemosis were the presenting complaints. Images and histopathology examinations confirmed the diagnosis. The patient underwent tumor resection through Endoscopic Endonasal approach, followed by a functional sinus drainage of the retained secretions. The patient made a good postoperative recovery and remained disease free at a 1-year follow up period.

INTRODUCTION

Neurilemmomas (schwannomas) are benign, slow-growing, usually solitary encapsulated perineural tumors. They arise from Schwann cells of the neural sheath of the peripheral nervous system, including motor, sensory and autonomic nerves. Embryologically, these tumors have neuroectodermal origin. They can occur throughout the body, but the head and neck region demonstrate a higher incidence of occurrence (25–45%) [1]. The VIII cranial nerve is the most common site for the tumor to develop (80%); other sites include the neck (8%), parotid gland (7%), cheek (7%), tongue (6%), scalp (6%) and sinonasal region (3–4%) [1, 2].

In 1910, Verocay established the neurinoma (schwannoma) as a pathologic entity. In 1920, the histologic patterns had been described by Antoni and categorized into Antoni A and Antoni B, which become the histologic hallmarks in the identification and classification of these benign tumor [3, 4]. In 1935, it was proposed that these tumors arose from nerve sheath elements and they were termed ‘neurilemmomas’ [5]. Patients with primarily sinonasal schwannomas that extend to the anterior skull base can present with nasal obstruction, epistaxis, hyposmia and pain. The preferred method of treatment is complete surgical removal when safely possible [6].

CASE REPORT

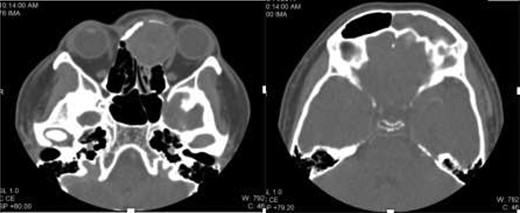

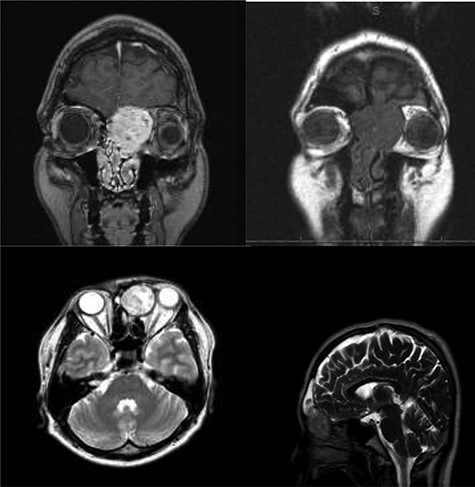

A 34-year-old Pilipino male has been referred to Otolaryngology Department at our hospital, as case of aggressive sinonasal tumor that is destructing the anterior skull base and left lateral orbital wall based on radiologic images. He was initially presented with a 4-month history of left eye proptosis, diplopia and chemosis. His complaint was not associated with epistaxis, headache or nasal blockage. Endoscopic examination at clinic revealed a mass at the level of left middle turbinate that is extending into the left nasal roof and destructing the upper part of the nasal septum. The Opthalmology Department evaluation revealed left mild proptosis with no extra-ocular muscle movement restriction or papillaedema. The Visual acuity showed normal vision. Upon review of his previously performed contrast enhanced images, including the computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging, a huge fronto-ethmoidal mass with bone erosion and compression of the left eye and left frontal lobe (Figs 1 and 2).

Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows an expansile mildly enhancing soft-tissue mass in the anterosuperior nasal cavity and encroaching upon left orbital cavity. The mass causing remodeling of the left medial orbital wall and extension up to the level of the cribriform plate. The mass also obstructs the drainage of left frontal sinus with consequent left frontal retained secretion and sinusitis.

MR imaging: T1-weighted postcontrast image shows an enhancing mass that extends up to the nasal vault. No definite dural enhancement is identified. sagittal and parasagittal T1-weighted postcontrast images help to further confirm the presence of cribriform plate dehiscence but a lack of gross dural disease. No intracranial extension.T2 and non contrast T1 images show absence of intratumoral hemorrhage or Cystic components.

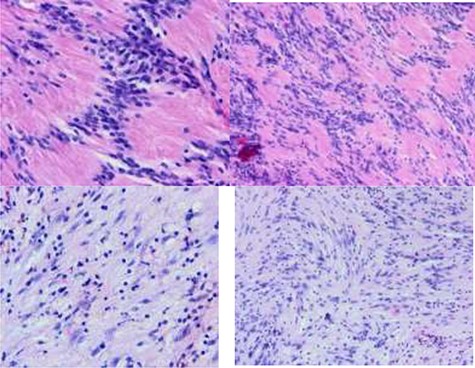

He underwent Endoscopic Endonasal tumor resection and the specimen was sent for histopathology evaluation. Intraoperatively, a cystic mass had occupied the left fronto-ethmoid area with skull base destruction and erosion of the left lamina paprecia. After tumor excision, the dura was exposed at the medial part of the anterior skull base and into the fronto-ethmoid area. However, no repair was required as no cerebrospinal fluid leak was noticed intraoperatively. A routine Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery, including ethmoidectomy and frontal sinus osteum opening, was performed after complete tumor excision. Postoperatively, he was monitored for 24 h and was discharged home in stable condition on simple analgesics and antibiotics. The histopathology report confirmed the diagnosis of a benign neurilemmoma as the spacemen’s slides showed neoplastic spindle cell proliferation that is arranged both compactly (Antoni A tissue) and loosely (Antoni B tissue). The Antoni A tissue contains frequent Verocay bodies. The neoplastic cells exhibit mild degree of nuclear pleomorphism with no detected mitosis or tumor necrosis. The overlying mucosa is stretched out (Fig. 3). On the follow-up clinic visits, no tumor recurrence was identified on a 1-year follow-up period and the patient’s condition was stable.

A biphasic histological pattern: Antoni A and Antoni B areas. Neoplastic palissading spindle-shaped Schwann cells proliferation that is arranged both compactly (Antoni A tissue) and loosely (Antoni B tissue). The Antoni A tissue contains frequent Verocay bodies. The neoplastic cells exhibit mild degree of nuclear pleomorphism with no detected mitosis or tumor necrosis. (Hematoxylin and eosin H%E, x10 and X40).

DISCUSSION

Schwannomas of sinonasal tract are very unusual. The origin of these tumors are from the Schwann cells in sheaths of the maxillary and ophthalmic divisions of the trigeminal nerve or from autonomic ganglia [7]. The small size of the nerves of origin, however, would explain why during the resection of sinonasal schwannomas can be rarely identified.

The most common presenting symptoms and signs of sinonasal tract shwannoma were nasal obstruction and headache. Others include olfaction impairment, anosmia, hyposmia, epistaxis and rhinorrhea with nasal discharge. Exophthalmus, facial swelling, epiphora and progressive vision reduction are less frequently described and are principally related to neoplasms of the orbital compartment. Cranial nerve palsy and intracranial extension have also been reported. Erosion of the neighboring bone structures may rarely be observed secondarily to necrosis, caused by the pressure of the slowly growing mass and, therefore, such a finding should not necessarily indicate malignancy [1].

On contrast enhanced imaging, the lesions may appear typically isointense in T1-weighed and hyperintense in T2-weighed scans, even though a typical pattern of vascularization in this kind of lesion has not been established previously [8].

Histopathologically, they generally present a biphasic histological pattern: Antoni A and Antoni B areas. The Antoni A areas are characterized by palisading spindle-shaped Schwann cells surrounding an acellular central region. This unit is called ‘Verocai body’. The Antoni B areas display loosely arranged smaller number spindle cells within a myxoid matrix that are not organized in a distinctive pattern and is prone to degeneration, hemorrhage and cyst formation. Immunohistochemical positivity for S-100 protein, found in neuroectodermic derived tissues, is also important for the diagnosis. Also, consistent with schwannoma morphology is positive immunostaining for neuron-specific enolase and vimentin and negative staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein, epithelial membrane antigen and CD56 [9].

Differential diagnosis may be difficult in some types of Antoni A tumors that may appear as neurofibromas, and other tumors of the peripheral nerves with a higher risk of malignancy. There is, by contrast, a very low risk of malignancy for schwannomas; however, in the literature [10], there are reports of malignant degeneration in long-standing benign schwannomas.

Schwannomas that arise primarily in the paranasal sinuses (sinonasal schwannomas) can also often mimic sinonasal malignancies, such as esthesioneuroblastoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, sinonasal melanoma, myxoid fibroblastic carcinoma, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas, inverted papilloma, sinonasal undifferentiated carcinomas, lymphomas, hemangiopericytomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas and metastatic carcinoma. Many of these lesions may present similarly as schwannomas with pain, discomfort, epistaxis, headaches, vision changes and obstruction and may also lead to local tissue destruction [11].

Neurilemmomas are fairly radio-resistant and the treatment of choice is surgical excision of the tumor within its capsule. Specific operative approaches depend upon the location of the tumor [12].

CONCLUSION

Neurilemmomas (schwannoma) of the front-ethmoid sinus is a rare pathological entity. It is a benign tumor with potential to local destruction and often the nerve of origin is difficult to establish. Histopathology is necessary for the definitive diagnosis. As schwannomas are not radiosensitive, complete surgical excision is essential.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

Youngerman JS, Lipper S, Mittleman M, Abramson AL. Neurilemoma of the sphenoid sinus.