-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

R.S. Laidlaw, N. Little, Repeated cannulation of umbilical hernia with Ventriculoperiotoneal shunt catheter, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2014, Issue 6, June 2014, rju059, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju059

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts are commonly used to manage hydrocephalus in both adult and paediatric populations. Whilst infection remains by far the most common complication leading to shunt revision other causes need to be considered. Our case report examines a 62-year-old female who presents for operative management of a Choroid Plexus Papilloma. Post-operatively she develops hydrocephalus and is managed with a VP shunt. Interestingly the distal end of the catheter cannulated an unknown umbilical hernia twice creating diagnostic dilemma. Issues around shunt insertion in the morbidly obese population and the basic science behind cerebrospinal fluid reabsorption are explored. Although this is a rare complication it should be considered in any post-operative shunt patient is slow to recover particularly if they are obese.

INTRODUCTION

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts are simple and effective way of draining excessive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). First reference to them in the literature can be traced back as far as the tenth century in Egyptian texts that describe ‘a spillage of clear fluid from the brain’ [1]. In 1765 Alexander Munro described the connection between the lateral and third ventricles and around this time the first ventricular catheters were being experimentally inserted to manage what we now know as hydrocephalus. Throughout the nineteenth century hydrocephalic infants were punctured via bulging fontanels with limited success. Carl Wernicke wrote in 1881 ‘When performed with aseptic precautions, this operation is intrinsically perfectly safe’. It was not until 1949 when Nulsen and Spitz inserted a ball valve shunt successfully into the caval vein that others began trialling such devices [2]. By 1960 there was at least four devices on the commercial market and today it is estimated that there is more than 120. Our case report presents an interesting complication of VP shunt insertion that has not yet been described in the adults.

CASE REPORT

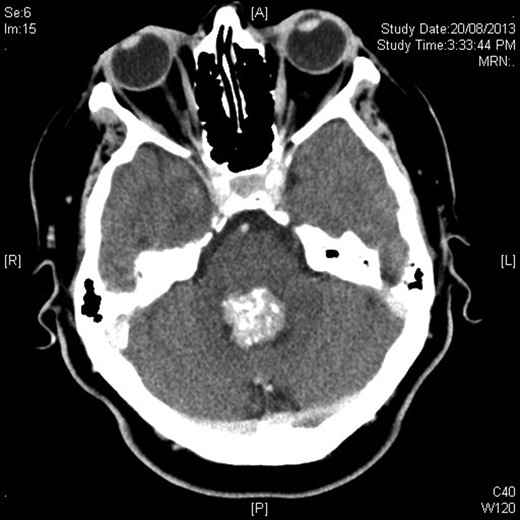

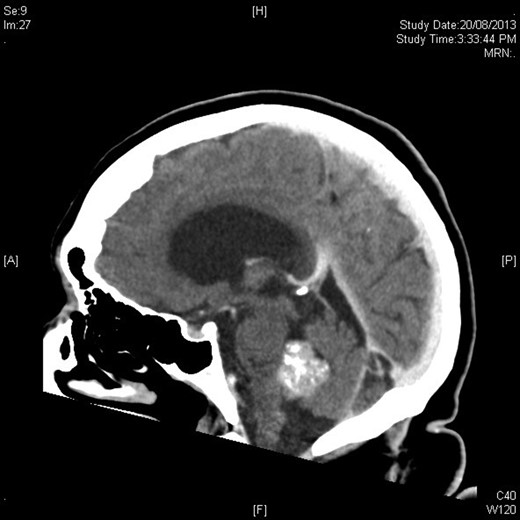

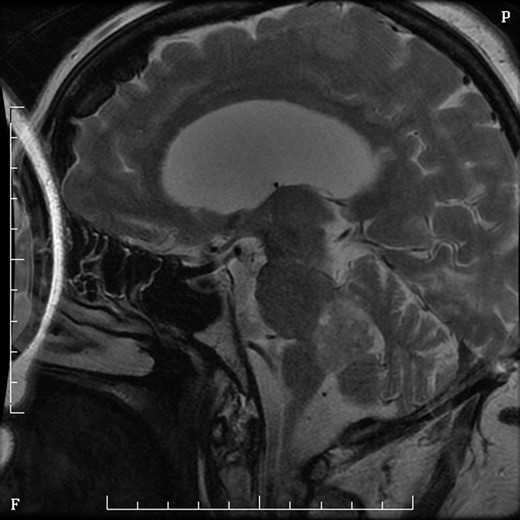

Mrs MM is a 62-year-old female who presented to our institution complaining of a 4-day history of nausea, vomiting and speech difficulties. She initially presented to a peripheral hospital following a fall at home and underwent workup for this. Clinically she scored a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 14 due to her confusion but had normal strength in all of her limbs. Initial computed tomography brain revealed a 2.6 × 2.5 × 2.1 cm rounded masses enhancing with contrast with areas of calcification in the fourth ventricle and obstructive hydrocephalus (Figs 1 and 2). The following day she underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain showed the lesion to be isodense on T1-weighted imaging mildly hypodense on T2-weighted imaging (Fig. 3), and there was no other pathology demonstrated apart from chronic microvascular ischemic changes.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT showing hyperdense rounded lesion in fourth ventricle.

Sagittal figure contrast-enhanced CT brain showing intimate relationship to choroid plexus and associated ventricular dilatation.

MRI sagittal T2 sequence with gadolinium showing rounded mass in fourth ventricle.

Two days later she underwent an operation to remove the lesion. She was positioned prone in mayfield head clamp and skull pins. A suboccipital craniotomy was performed to gain exposure and the lesion was removed using stereotaxy and operating microscope. Frozen section at the time of surgery was suggestive of Choroid Plexus Papilloma and indeed the formal histopathology confirmed this some days later. Day 1 post-operatively Mrs MM. had cranial nerve VI and VII palsies and was slow to recover. On post-operative day 2 she had a sudden drop on GCS and urgent CT brain demonstrated obstructive hydrocephalus and she underwent insertion of VP shunt (Fig. 4).

On Day 2 post VP shunt insertion, she was noted to be slow to recover and CT abdomen was performed. This demonstrated that the distal catheter tip was not in the pleural space but entered the abdomen and was redirected out along a tract into an umbilical hernia (Fig. 5). The following day she was taken back to theatre and the VP shunt was revised, and good visualization into the abdomen gave the impression that it was correctly in place. Repeat CT abdomen was performed to confirm placement and to our surprise the catheter had re-entered the same tract and travelled into the umbilical hernia (Fig. 6).

Sagittal figure CT abdomen, demonstrating catheter entering abdomen and re-exiting out the umbilical hernia.

Coronal section CT abdomen after second shunt revision showing catheter again protruding out through umbilicus into hernia sac.

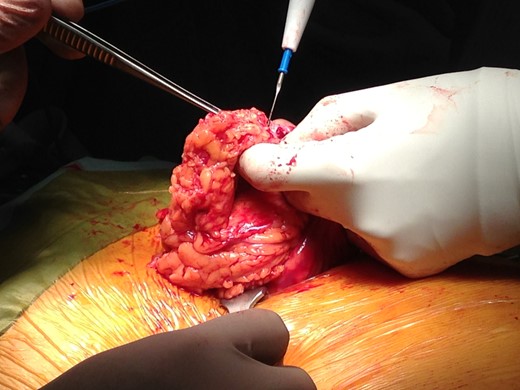

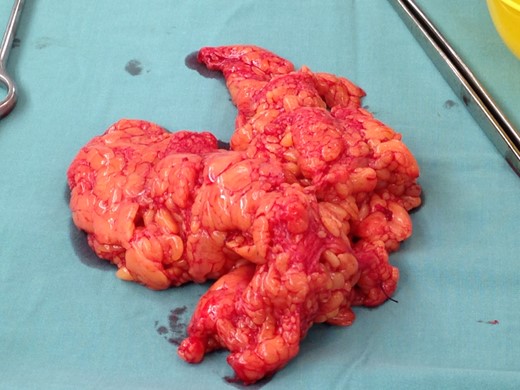

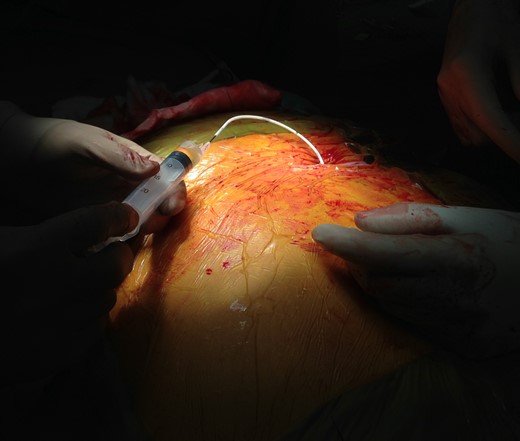

Following two failed attempts at inserting the VP shunt, assistance from a general surgeon allowed us to proceed. Repair of umbilical hernia was performed on this occasion as the shunt was revised again with success. A large piece of strangulated peritoneum (Figs 7 and 8) was removed and the catheter tip was checked for patency (Fig. 9). The distal end was then placed through the peritoneal wall and secured with a silk tie and purse string knot.

Intraoperative figure demonstrating shunt patency by aspirating CSF from distal catheter end.

DISCUSSION

There is little literature describing VP shunts entering umbilical hernias in adults. In the paediatric literature Wani et al. presented a single case of an 18 month old with congenital hydrocephalus presenting with fever some 6 months post VP shunt insertion [3]. In this case due to the small size of the patient, the distal catheter could easily be palpated at the umbilicus making the diagnosis obvious and easily confirmed with bedside ultrasound. In the obese patient, it is difficult to see or palpate any changes in the abdomen to suggest an umbilical hernia. There have been other case reports of inguinal hernias, scrotum, liver, vagina and internal jugular veins being cannulated but the distal catheter tip [4, 5].

Despite the catheter tip being extruded out of the umbilical hernia and it being incarcerated, perhaps there is an argument of not interfering with it? The lining of the hernia is still visceral peritoneal tissue found in the abdomen and one could assume that it would be just as capable of absorbing the CSF as the rest of the peritoneum. In theory it should not make any difference if the catheter is in the hernia or intraperitoneal as long as there is a mechanism for the fluid to be reabsorbed. In this case, reabsorption may have been limited by compartmentalization of the sac which leads to raised compartment pressure. There are no other cases reported in the literature at the time of writing this article.