-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Noufel Alshadood, Sajjad Ghanim Al-Badri, Ali Naser Aldarawsha, Mohamed Samy Elazab, Manar Mohammed Mahdi, Flayyih Hasan Yousif, Ahmed Shamil Hashim, Hussein Mohsin Hasan, Nabeel Al-Fatlawi, A rare case of giant hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma in a pediatric patient: diagnostic and surgical challenges, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 4, April 2025, rjaf247, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf247

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma is a rare benign liver tumor in pediatric patients, typically presenting within the first two years of life. This case involves a 10-month-old female who initially presented with repeated vomiting and was misdiagnosed with a hepatic hemangioma. Subsequent imaging revealed a large, multicystic hepatic mass, and a biopsy indicated spindle cell proliferation, initially suggesting embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Due to uncertainty in the initial histopathological diagnosis, the case was discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting, and the decision was made to proceed with surgical resection. The final diagnosis of hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma was confirmed postoperatively. The patient underwent successful tumor resection, sparing the liver, with no postoperative complications. This case highlights the diagnostic challenges associated with large pediatric hepatic masses and underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach for successful outcomes in similar cases.

Introduction

Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma (HMH) is a rare benign tumor of the liver, predominantly affecting pediatric patients, especially those under the age of two. It constitutes around 8% of pediatric liver tumors and is often characterized by its large size and multicystic appearance. HMH typically arises from a developmental anomaly in the liver's mesenchymal tissue rather than being a true neoplasm. Although benign, HMH can grow rapidly, causing significant symptoms such as abdominal distension, respiratory distress, vomiting, and poor weight gain due to compression of adjacent organs [1–3].

The condition's presentation varies based on the tumor's size, ranging from incidental findings in small lesions to life-threatening complications in larger cases. While most cases are managed surgically, the gold standard is complete resection to prevent recurrence and, in rare cases, malignant transformation into undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma. In complex cases where resection is not feasible, liver transplantation may be considered a therapeutic alternative, although it is controversial for benign tumors [4].

Radiological imaging is crucial in diagnosing HMH, particularly using dynamic post-contrast MRI and ultrasound, which can delineate the tumor's cystic and solid components. Histopathology remains essential for confirming the diagnosis [5].

Case presentation

A 10-month-old female initially presented with repeated vomiting during her first three months of life. During this period, a routine sonographic evaluation identified a hepatic lesion suggestive of a hemangioma. She was placed on follow-up without active treatment, and the vomiting resolved spontaneously. As symptoms improved, follow-up was discontinued.

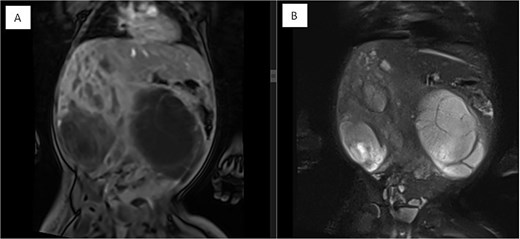

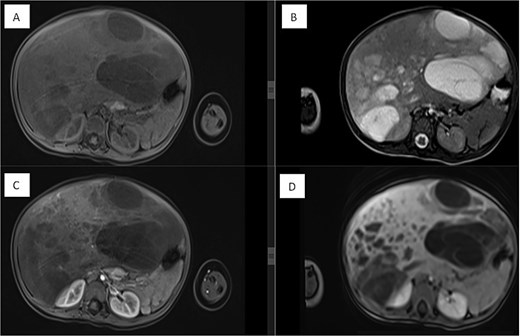

Several months later, she developed progressive abdominal distension and recurrent vomiting, prompting further evaluation. A CT scan of the abdomen revealed a large heterogeneous hepatic mass primarily occupying the right lobe, measuring 12.6 × 8.8 × 14 cm, with multicystic areas and soft tissue enhancement. MRI also demonstrated a large right hepatic lobe mass with mass effect and heterogeneous enhancement (Figs 1 and 2). Mild upper abdominal lymphadenopathy was noted (largest node 8 × 10 mm), along with a right-sided inguinal hernia. Differential diagnoses included HMH, with hepatoblastoma and undifferentiated sarcoma considered less likely. A chest CT showed mild pericardial effusion and an inflammatory appearance.

Coronal MRI images of the abdomen showing a mass effect in the right hepatic lobe. (A) Coronal T1 post-contrast and (B) coronal T2 HASTE FS images demonstrate spatial relationships, including compression of the right kidney, pancreas, and major vessels, with no invasion. The mass displaces bowel loops inferiorly and causes an anterior abdominal wall bulge.

Dynamic MRI of the abdomen demonstrating a large, partially cystic, and solid lesion arising from the right hepatic lobe. (A) Axial T1 and (B) axial T2 images show the lesion’s mixed composition and internal structure. (C) Arterial and (D) portovenous phase post-contrast images reveal heterogeneous enhancement of the solid and septal components.

An ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed. Pre-biopsy ultrasound identified a large mass displacing and compressing the right kidney and liver, with no signs of infiltration. The lesion appeared multicystic, raising suspicion for neuroblastoma; Wilms tumor was considered less likely. Histopathology revealed spindle hyperchromatic cell proliferation in a vascularized, mildly myxoid stroma. Tumor cells stained positive for desmin, raising concern for embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, with WT1 positivity in stromal cells.

Due to the uncertainty of the histopathological diagnosis, the case was discussed in a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting, including radiology, oncology, surgery, and pathology. Given the imaging findings, clinical status, and inconclusive biopsy, the MDT recommended surgical resection for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

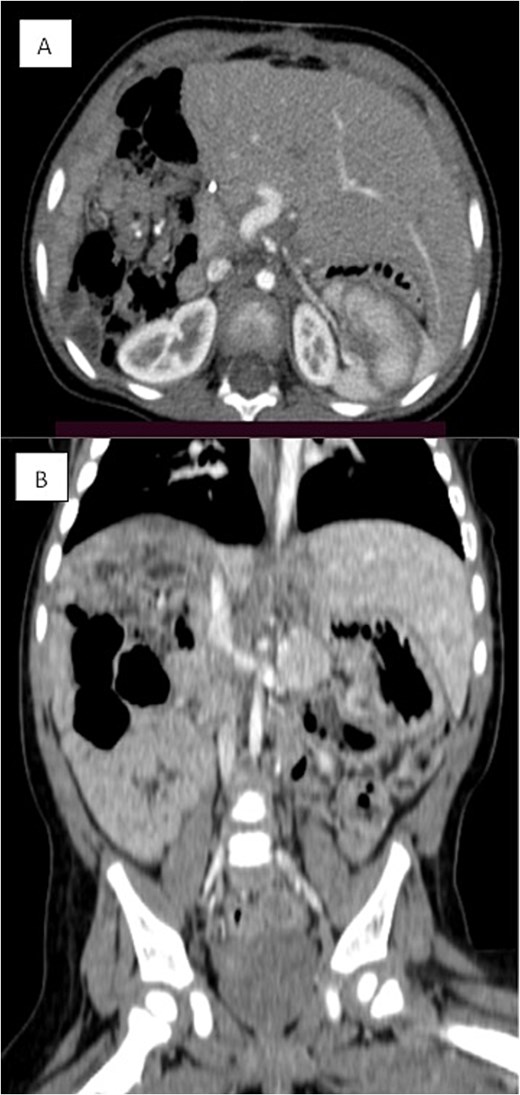

A right-sided hepatectomy was initially planned; however, intraoperatively, the tumor was resected with a safe margin while preserving unaffected liver tissue. Postoperative liver volumetry confirmed adequate remaining liver volume (40%) (Fig. 3). Surgery was completed without complications.

Triphasic CT examination of the abdomen post-right hepatectomy. (A) The axial view shows a clear operative bed with no residual enhancing lesions or collections. The (B) coronal view demonstrates compensatory hypertrophy and enlargement of the left hepatic lobe. Herniated bowel loops are visible, filling the right hypochondrial subphrenic region.

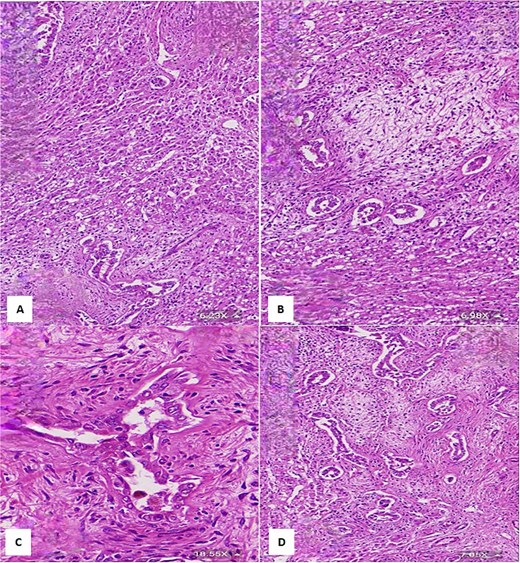

Final histopathological examination of the resected 17 cm mass confirmed the diagnosis of HMH (Figs 4 and 5). The patient recovered well postoperatively.

(A) Histological section showing interspersed islands of hepatocytes with retention of normal cell plate architecture (hematoxylin & eosin, 6.23×). (B) Myxoid area with benign duct structures and interspersed normal hepatocytes (hematoxylin & eosin, 6.98×). (C & D) Dilated and branching bile ducts show no cytological atypia (hematoxylin & eosin: C- 18.55×, D- 7.05×).

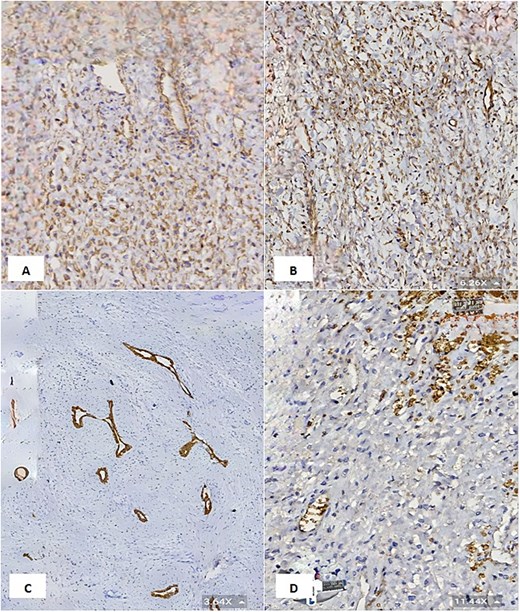

(A & B) Vimentin immunostain demonstrating positive cytoplasmic staining in neoplastic cells (6.26×). (C) CK7 immunostain highlights the benign bile duct epithelium (3.64×). (D) GLUT1 immunostain shows negative staining in neoplastic cells and positive staining in red blood cells (internal control) (11.44×).

This case illustrates the diagnostic complexity of pediatric hepatic masses and reinforces the value of multidisciplinary coordination in guiding management decisions. Early surgical intervention in the setting of diagnostic uncertainty contributed to both definitive diagnosis and a favorable clinical outcome.

Discussion

The case of a 10-month-old female with a giant HMH highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in pediatric patients presenting with large hepatic masses. Mesenchymal hamartomas, though benign, often exhibit complex clinical presentations, as seen in this case, where the patient initially presented with vomiting and later developed significant abdominal distension. This progression underscores the diagnostic difficulty, as the lesion was initially misidentified as a hemangioma. Despite biopsy suggesting rhabdomyosarcoma, the diagnosis remained uncertain. The case was discussed in an MDT meeting, and the decision was made to proceed with surgical resection. The final diagnosis of HMH was confirmed postoperatively [1, 5].

HMHs are rare, constituting about 8% of pediatric liver tumors, and they predominantly present within the first two years of life. These tumors can exhibit various imaging characteristics, from cystic to solid masses, complicating differential diagnosis [3]. In this case, the patient’s lesion was large and multicystic, a presentation typical of giant mesenchymal hamartoma [6]. The elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in this patient, a marker often associated with malignant liver tumors like hepatoblastoma, further complicated the diagnostic process. This mirrors findings in other cases where AFP levels led to diagnostic uncertainty, prompting biopsy and histopathological examination to confirm the benign nature of the tumor [2, 5].

The initial misdiagnosis in this case reflects the challenge of differentiating between benign and malignant liver lesions based on imaging alone. Other reports have highlighted the importance of comprehensive imaging, particularly dynamic post-contrast MRI and ultrasound, in defining the nature of these tumors [6, 7]. For instance, studies have shown that mesenchymal hamartomas' cystic and solid components are well-depicted on MRI, which aids in distinguishing them from malignant neoplasms like hepatoblastoma and undifferentiated sarcoma [8, 9]. The patient’s lesion was similarly heterogeneous in this case, with multicystic areas and solid components. Advanced imaging modalities, particularly MRI, are crucial in such cases, allowing for better characterization of the tumor's morphology and its relationship with surrounding structures [10].

Histopathology remains the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of mesenchymal hamartoma, as was the case here [1]. The biopsy revealed spindle cell proliferation within a myxoid stroma, with strong desmin positivity, initially suggesting a rhabdomyosarcoma diagnosis. However, due to uncertainty in the histopathological findings, the team opted for surgical resection without initiating neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. The postoperative histopathology confirmed the diagnosis, emphasizing the importance of surgical intervention for treatment and diagnostic confirmation [11]. Immunohistochemistry can also help in differentiating malignant tumors from HMHs, where malignant tumors usually stain positive for markers like desmin, myogenin, and MyoD1, while hamartomas lack these markers [12]. This desmin marker positivity added one more diagnostic challenge to this case, suggesting the diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma. Therefore, we must have a detailed assessment of the age of onset, clinical presentation, imaging characteristics, and histopathology to differentiate between these two tumors, as they have overlapping clinical and imaging features.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is a malignant condition requiring aggressive treatment, whereas HMH is a benign lesion with an excellent prognosis post-resection. Surgical management typically treats mesenchymal hamartomas, especially for large, symptomatic lesions. Complete resection, when feasible, is preferred to avoid complications such as local recurrence or, in rare cases, malignant transformation into an undifferentiated sarcoma [4, 13]. In this case, the surgical team successfully resected the tumor without necessitating a hepatectomy, thus preserving liver function. This approach aligns with other case reports where complete resection is emphasized to prevent potential future complications [13]. In a study by Hassan et al., complete surgical excision was identified as the gold standard for managing large mesenchymal hamartomas, with excellent long-term outcomes following the procedure [14].

Postoperative recovery in this patient was uneventful, consistent with other reported cases where successful surgical resection led to favorable outcomes [1, 13]. Regular follow-up is crucial to monitor for recurrence, especially given the rare potential for malignant transformation [15]. In a few cases, incomplete resection has led to recurrence, further underscoring the importance of achieving complete tumor removal during the initial surgery [2, 13].

Conflict of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest to report.

Funding

No source of funding was received.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient family for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Ethics approval

Our institution does not require ethical approval to report individual cases or case series.