-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

María Guadalupe Sánchez-Villegas, Daniel Zúñiga-Mejía, Elio Germán Recinos-Carrera, Gerardo Gabriel Montero-Flores, Alejandra Nuñez-Venzor, Intestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma with peritoneal lymphomatosis mimicking acute appendicitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 3, March 2025, rjaf147, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf147

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The gastrointestinal tract is the most frequent extranodal site of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for up to 40% of cases. However, appendiceal lymphoma is exceptionally rare, with peritoneal involvement being even rarer. Appendiceal lymphoma often mimics acute appendicitis (AA), although it is an uncommon initial manifestation of intestinal NHL, complicating diagnosis. We report a 29-year-old male with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who presented with AA. An open appendectomy was planned; however, intraoperative findings— including cecal induration, ascites, peritoneal thickening, and macronodular lesions on the peritoneum and intestines—led to abandonment of the procedure. Postoperative evaluation excluded peritoneal tuberculosis (PTB), while computed tomography (CT) suggested peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). Histopathological analysis of a parietal peritoneum specimen provided the definitive diagnosis of NHL. Appendiceal NHL should be considered in HIV-positive patients with AA. Routine histopathological evaluation and surgical intervention are essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

Introduction

Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma (PGIL) is rare, accounting for 1–4% of all gastrointestinal tumors. In advanced stages, it can disseminate, obscuring its origin and mimicking the more frequent secondary gastrointestinal involvement. The gastrointestinal tract is the most frequent extranodal site, representing up to 40% of cases, predominantly due to NHL. The stomach (47%), small intestine (27%), and colon (17%) are the most commonly affected sites [1]. Appendiceal lymphoma, first described by Kundrat in 1893, is exceptionally rare, comprising only 1.7% of appendiceal neoplasms [2, 3]. PGIL symptoms are nonspecific, with abdominal pain being the most common presentation across all sites [4]. Appendiceal involvement typically mimics AA, although it is an uncommon initial manifestation of intestinal NHL, with peritoneal involvement being even rarer [5].

Case presentation

A 29-year-old male with a 7-year history of HIV, on Biktarvy for 3 years, presented with a 2-week history of periumbilical pain, nausea, vomiting, and later, right iliac fossa pain and diarrhea. Physical examination revealed abdominal distension, reduced peristalsis, and tenderness at McBurney's point.

Laboratory results showed white blood cell count 8.1 × 103/μL, neutrophils 5.04 × 103/μL, lymphocytes 2.11 × 103/μL, hemoglobin 14.1 g/dL, platelets 508 × 103/μL. Blood chemistry indicated elevated blood urea nitrogen 32.7 mg/dL, urea 70 mg/dL, alanine aminotransferase 64 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase 68 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase 291 IU/L, and C-reactive protein 11.97 mg/dL. The CD4 T-cell count was 223 cells/μL, with an undetectable HIV viral load. Coagulation tests and serum electrolytes were normal.

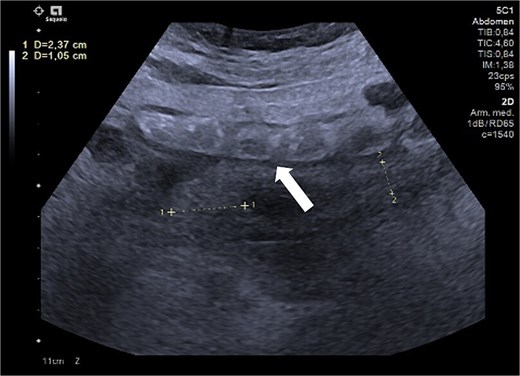

An abdominal ultrasound suggested AA (Fig. 1), prompting an open appendectomy. Intraoperative findings included cecal induration with distorted anatomy, thickened parietal peritoneum, 100 mL of ascitic fluid, and macronodular lesions on the peritoneum and intestines. Consequently, the appendectomy was not performed, and only a peritoneum biopsy and ascitic fluid sample were obtained for analysis.

Ultrasound of the right iliac fossa showing the cecal appendix (arrow), measuring 1.1 cm in diameter with a wall thickness of 0.34 cm. It demonstrated increased vascularity and non-collapsibility with compression.

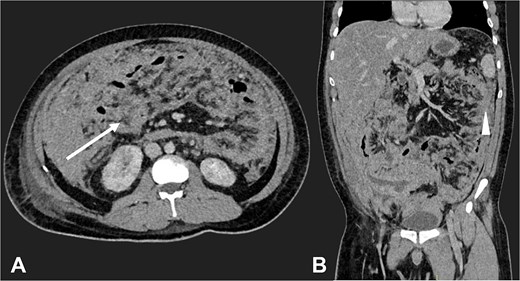

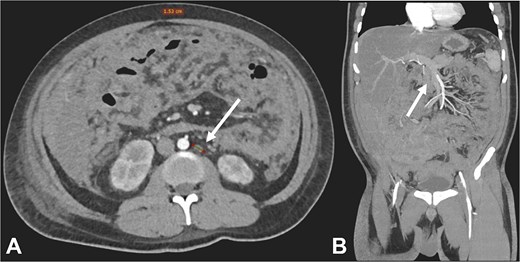

Postoperatively, suspected PTB was evaluated. Diagnostic tests, including sputum smear microscopy and GeneXpert MTB/RIF, peritoneal fluid culture and microscopy, and auramine-rhodamine stool staining, were negative. Thoracoabdominal CT (Figs 2 and 3) revealed generalized PC, plaque-like involvement at the hepatic flexure of the colon, and inflammatory lymph nodes. Histopathology provided the definitive diagnosis of NHL (Figs 4 and 5). Following an uneventful postoperative recovery, the patient was discharged after one week and referred to a tertiary care center, where chemotherapy was initiated, leading to significant improvement.

Contrast-enhanced CT in the venous phase: Axial view (A) and coronal reconstruction (B) demonstrated nodular thickening of the peritoneum with vascular enhancement, peritoneal implants measuring up to 6 mm (arrow), and plaque-like implants along the splenic margin (head arrow).

Contrast-enhanced CT in the arterial phase: Axial view (A) and coronal reconstruction (B) demonstrated mesenteric lymphadenopathy measuring up to 1.53 cm (white arrows).

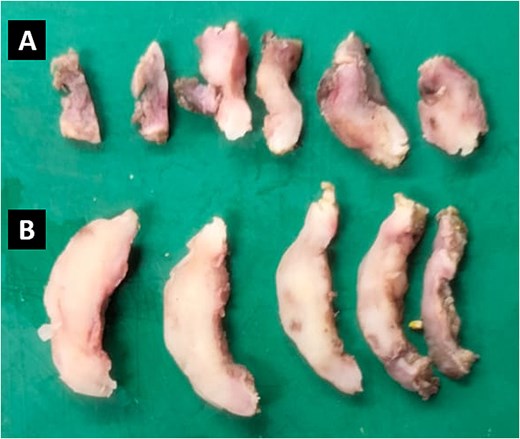

Representative sections of two tissue samples from the parietal peritoneum. The smaller fragment (A) measures 2.0 × 1.0 × 0.3 cm, has an irregular oval shape, and exhibits a soft consistency. The larger fragment (B) measures 3.5 × 2.0 × 0.3 cm, has an irregular laminar shape, and is similarly soft.

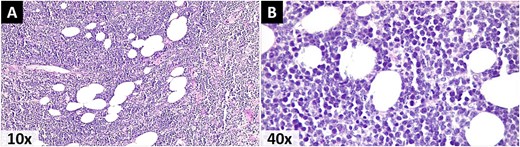

Photomicrographs stained with Hematoxylin and eosin. A) A malignant lymphoproliferative neoplasm infiltrating the omental adipose tissue, morphologically consistent with NHL. B) Small cells with scant eosinophilic cytoplasm, pleomorphic nuclei with dispersed granular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and atypical mitoses.

Discussion

Most gastrointestinal NHL originate from B cells, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) being the most common subtype overall and specifically in the appendix, where it is followed in frequency by Burkitt lymphoma [1, 5].

HIV-positive patients have a significantly higher risk of NHL, which often presents at advanced stages with extranodal involvement. HIV-associated lymphomagenesis occurs through two mechanisms: 1) Uncontrolled proliferation of Epstein–Barr virus-infected B cells due to impaired T-cell control, driving Epstein–Barr-positive NHL subtypes; and 2) Chronic B-cell activation from antigenic stimulation by HIV or other infections, exacerbated by bacterial translocation from gut CD4+ T-cell depletion. This activation promotes class-switch recombination, somatic hypermutation and mutations [6].

Lymphomatous infiltration of the appendix causes diffuse wall thickening, increasing its diameter to 2.5–4.0 cm. On ultrasound, it appears hypoechoic, while CT shows homogeneous attenuation and poor enhancement. The appendix retains its vermiform shape and may show aneurysmal dilation. Abdominal lymphadenopathy improves diagnostic specificity and, combined with intestinal involvement, suggests secondary appendiceal involvement. However, definitive diagnosis of appendiceal NHL requires excisional biopsy [7, 8].

The prevalence of AA is higher in HIV-positive patients (0.6–3.6%) than in the general population (0.1%). In this group, additional causes of AA to consider include immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome following antiretroviral therapy initiation, opportunistic infections (e.g. Kaposi’s sarcoma, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycobacterium spp., Salmonella, cytomegalovirus, cryptosporidiosis, histoplasmosis, and amebiasis), and potential direct HIV effects on the appendix [9].

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) is also more common in HIV-positive individuals, with the abdomen being the sixth most frequent site and PTB comprising 4.9% of all EPTB cases. Diagnosing PTB is challenging due to nonspecific symptoms, insidious onset, and diagnostic limitations. It should be suspected in cases of exudative ascites with lymphocyte predominance, a serum-ascitic albumin gradient <1.1 g/dL, and adenosine deaminase >30 U/L. Smear and culture of ascitic fluid have low sensitivity (<5% and 35%, respectively), while peritoneal biopsy smear and culture are more sensitive (50–63% and 70%, respectively). Histopathological and/or microbiological analysis of a laparoscopic peritoneal biopsy is the gold standard [10, 11].

Peritoneal lymphomatosis (PL) is a rare manifestation of lymphoma, attributed to the absence of lymphoid tissue in the peritoneum. Proposed dissemination pathways include the gastrocolic ligament, transverse mesocolon, and visceral peritoneal surfaces. Between 2001–2023, 46 cases have been reported, predominantly involving high-grade lymphomas, particularly DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma. PL is often misdiagnosed as PC, it also has overlapping imaging findings with mesothelioma, pseudomyxoma, sarcomatosis, and PTB [12]. O’Neill identified distinctive CT features of PL: large nodules (>5 cm in 75%, p = 0.004), splenomegaly (p = 0.002), and more frequent lymphadenopathy (p < 0.0001), with 76% showing >10 affected lymph nodes (p = 0.01). Mesenteric masses were more common in PL (41%) than in PC (2%), with 78% exceeding 10 cm. In this case, lymphadenopathy was the sole feature suggestive of PL, whereas peritoneal thickening resembled PC. Although fine nodularity is uncommon in PC, when present, it is often ill-defined and may coalesce into plaques, as seen in this patient’s CT findings [13].

The Lugano classification is the standard for NHL staging and is performed using positron emission tomography/CT, preferred for its high sensitivity to extranodal involvement [14]. Intestinal NHL treatment often relies on studies primarily focused on gastric lymphoma. Chemotherapy is the cornerstone for aggressive and widespread intestinal NHL, as in this case, while surgery is reserved for refractory cases, localized disease, and complications (bleeding, perforation, occlusion). Surgery combined with chemotherapy may improve overall and cancer-specific survival; however, patient stratification based on surgical timing and indications is necessary for definitive conclusions [15].

Conclusions

Although NHL of the appendix is rare, surgeons should include it in the differential diagnosis of AA, particularly in high-risk patients such as those with HIV. Urgent surgery may be required to manage complications. This case underscores the importance of routine histopathological examination of appendectomy specimens and highlights surgery's critical role in achieving a definitive diagnosis.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).