-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hongyu Ruan, Xiaoxia Zhu, Suling Xu, Songting Wang, Feng Yang, Guixiu Li, Xinyu Jiang, Keyu Zhao, Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia misdiagnosed as cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 1, January 2025, rjae838, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae838

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is a rare histopathological reaction. Cases of PEH have been infrequently reported, and it’s even rare to appear as a postsurgical complication. This case report describes the development of multiple masses and purulent discharge around an abdominal scar following surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma, which morphologically resembles squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), though pathology revealed no signs of malignancy. The underlying mechanism of PEH has not been fully characterized. This case report may alert clinicians and pathologists to rare diseases and update the list of postoperative complications.

Introduction

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is a rare benign hyperplastic condition secondary to trauma, inflammation, infection, tumor and other underlying diseases [1]. PEH closely resembles cutaneous SCC, making clinical misdiagnosis a common issue.

We present here the case of a patient who exhibited squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)-like skin changes at a surgical incision for hepatocellular carcinoma and was initially considered to have cutaneous metastases from a hepatic malignancy.

Case report

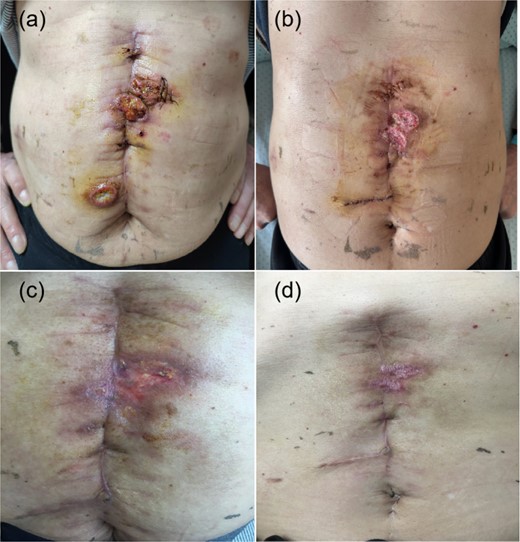

We describe a 70-year-old male patient referred to our department with multiple lumps around an abdominal scar that had been present for one month. Two months prior, he had undergone a hepatectomy for liver cancer in the hepatobiliary surgery department, and the surgical incision had shown poor healing. One month post-surgery, multiple red plaques with central ulcers and purulent discharge appeared around the incision. The patient occasionally experienced pruritus but denied any pain, fever, or chills. He was initially treated at an external hospital with levofloxacin and dressing changes for a suspected skin infection. However, the plaques continued to enlarge and ulcerate. A biopsy was performed at the external hospital, indicating SCC (Fig. 1a).

PEH lesions. Abdominal scar accompanied by lumps and purulent discharge (a). Follow-up photos taken at 1 week, 1 month, and 1.5 months postsurgery (b, c, d).

The patient had a medical history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and liver cancer but no history of smoking and alcohol abuse. He denied any prior similar complaints or relevant family history. On examination, three red lumps (~3 × 2 cm) and two smaller lumps (~1.5 × 1.5 cm) with purulent secretions and erosive were observed around the linear scar in the abdomen. The lumps had purulent secretions, and a flushed erosive surface was observed around the linear scar. Positron emission tomography revealed thickening of the skin in the abdominal incision with increased uptake of flurodeoxyglucose (FDG) in the peritoneum around the incision. No FDG uptake was detected in the surgical margin or residual liver tissue. Other examinations were unremarkable.

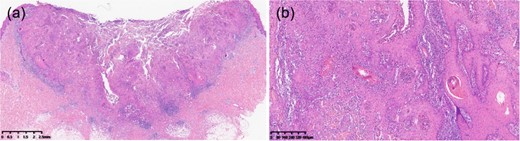

Despite the pathological report and clinical presentation suggesting SCC, the rapid enlargement of the lesions near the surgical site raised the possibility of alternative diagnoses, including infection-induced granulomatous lesions. Initially, photodynamic therapy (PDT) combined with limited excision was planned. However, given the rapid progression and the need for a definitive diagnosis, we performed multipoint excision of the lesions for comprehensive histopathological evaluation. Histopathological findings revealed evidence of epidermal necrosis and defect with PEH. There was no evidence of heteroplasia, but the dermis exhibited marked infiltration of inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils (Fig. 2a and b).

Histopathological examination, Histopathological analysis with hematoxylin–eosin staining (×80) revealed epidermal necrosis and PEH (a). Histopathological analysis with hematoxylin–eosin staining (×400) demonstrated inflammatory cell infiltration without cytological atypia (b).

Subsequently, an in-hospital multidisciplinary consultation involving dermatology, pathology, and hepatobiliary specialists confirmed the diagnosis of PEH. The patient’s lesions significantly improved after combined treatment with excision and PDT. At follow-up 1.5 months later, the wound had healed well, with no new lumps or ulcers observed (Fig. 1b–d).

Discussion

PEH is a rare histopathological reaction secondary to trauma, infection, tumors, and other underlying diseases, often requiring differentiation from SCC and keratoacanthoma [2]. Histopathological features remain the gold standard for differential diagnosis [3]; PEH is characterized by epidermal and adnexal hyperplasia with papillomatosis. Cells are well-differentiated and lack nuclear atypia, abnormal mitoses, or dyskeratosis. Recent studies reported that PEH exhibits characteristic features on dermoscopy [4] and PCR assays [5], which differ from those of SCC and provide potential diagnostic value.

This report presents a rare case of PEH around the surgical incision site of a patient with liver cancer who was misdiagnosed with SCC. Similar cases have been reported in recent years [6]. However, there are no reports related to PEH after surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma.

PEH likely developed as a pathological response to trauma or infection. Postoperative wound care and early recognition of PEH may prevent such complications. Multiple biopsies and careful histopathological evaluation are essential for accurate diagnosis. This case underscores the importance of including PEH in the differential diagnosis of SCC-like lesions, particularly in the postoperative setting.

Conclusion

This case emphasizes the diagnostic challenges posed by PEH, a benign condition that closely mimics SCC. Comprehensive excision, thorough histological evaluation, and multidisciplinary consultations are crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Recognizing PEH as a potential complication after surgery may improve patient management and reduce unnecessary anxiety.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The Project of NINGBO Leading Medical & Health Discipline (No. 2022-F23). The Public Welfare Projects of Ningbo, China (No. 2022S065). The Health Major Science and Technology Planning Project of Zhejiang Province, China (No. WKJ-ZJ-2411). The Ningbo Major Research and Development Plan Project(2024Z228).

Ethical approval

Informed consent for publication of this paper was obtained from The First Affiliated Hospital of Ningbo University and all authors. Approval 2024 NO.111RS-YJ01.

Ethics statement

We thank the patient for granting permission to publish this information.