-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Aikaterini Sarafi, Nikolaos Tasis, Eleni Mpalampou, Maria Igoumenidi, Evdokia Arkoumani, Alexandros Tzovaras, Dimitrios P Korkolis, Theodoros Tsirlis, Primary extrarenal papillary type II renal cell carcinoma presenting as a pelvic mass: a case report and review of the literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 7, July 2024, rjae433, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae433

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We report a case of a 57 years old woman with a solitary mass located in the pelvis diagnosed as an extrarenal papillary renal cell carcinoma, in the absence of a primary renal cancer. The diagnosis was based on cytomorphological features and further confirmed by immunochemistry findings following surgical excision. The hypothesis of a tumor developing in a supernumerary or ectopic kidney was excluded, since no normal renal tissue could be identified in the specimen and in the preoperative computed tomography and MRI images.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common kidney malignancy in adults [1]. Papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC), accounting ~10–15% of all RCCs, is the second most common subtype following clear renal cell carcinoma (cRCC). PRCC is further subcategorized in type I and II based on a variety of histopathological features. Type II pRCC is associated with a worse prognosis than type I [2]. Radical nephrectomy is the mainstay therapeutic option in case of resectable disease while the role of adjuvant therapy remains controversial [3].

Metastasis from RCC at diagnosis varies from 30 to 40% [4]. There have been several reports of extraordinary distant metastases from RCC [5]. However, primary extrarenal RCC with intact bilateral kidneys is an uncommon presentation [6]. Furthermore, the extrarenal localization of primary pRCC is extremely rare with only four cases reported in the literature. We present the fifth case of a primary extrarenal type II pRCC located in the pelvis of a 57 years old woman.

Case report

A 57 years old woman presented to our department with a pelvic mass, which was diagnosed during a routine gynecological ultrasound exam. The patient did not report any bowel or urinary symptoms. Except from hypothyroidism under treatment, her past medical history was unremarkable. The past surgical history included two cesarean sections. The patient was never a smoker and reported no allergies or alcohol intake. Blood tests, including tumor markers (NSE, CA19-9, CEA), were within normal limits.

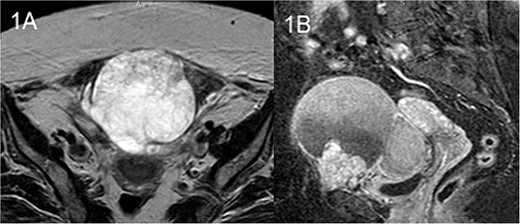

The patient underwent an MRI which revealed a large cystic pelvic mass, measuring 10.3 x 9 x 11.1 cm, with septations and solid component in contact with the anterior abdominal wall, and the bladder as well (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of vascular invasion from the mass. A colonoscopy followed in order to exclude the involvement of the colon and rectum, which was normal.

MRI T2 axial (A) and sagittal (B): solitary mass in contact with rectus abdominis.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen was unremarkable for any additional lesions. Both kidneys appeared to be of normal size, location, and enhancement.

Due to the suspicion of malignancy, surgical exploration was decided at the MDT meeting. A diagnostic biopsy was excluded due to the high suspicion index of ovarian cancer. The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy via a midline incision. The mass was found to be adherent to the urinary bladder caudally, the rectus abdominis muscle anteriorly as well as to the left ovary laterally. Carefully mobilization of the mass from the adjacent structures took place and en block resection of the mass was completed along with partial cystectomy, partial rectus excision and bilateral adnexal resection. Operative time was 150 min and the blood loss was minimal. The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course and was discharged on postoperative Day 5.

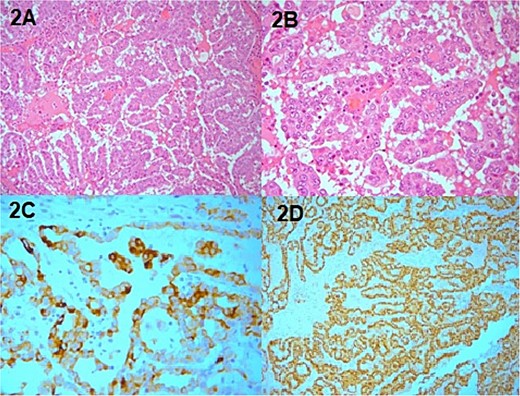

Macroscopic examination revealed a tumor measuring 10 x 9 x 8.5 cm. On histopathological evaluation, development of papillary carcinoma including papillae, tubules and distended papillae with edema and hemorrhagic features was noted. Papillary architecture of the mass included pseudostratified layers of large cells, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, and typical nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The immunochemistry was positive for CK7, PAX-8, and AMACR (Fig. 2). The stains for C-kit and CD10 were negative. CK20 and CDX2 stains were performed in order to exclude colonic origin and were negative. Stains WT-1, ER, PR, and GATA-3 were also performed in order to exclude breast and adnexa origin and were negative. Furthermore, stains carletinin and D2-40 as well as TTF-1 and thyroglobulin were performed, in order to exclude mesothelioma, lung, and thyroid origin. The pathological diagnosis was in keeping with extrarenal papillary renal carcinoma type II. In the absence of any abnormalities and masses of the patient’s kidneys, the carcinoma presumably developed on ectopic renal tissue. However, following meticulous cross sectioning of the specimen, no normal renal tissue was identified. The margins of excision were clear.

Pathology specimen, (A) H&E X20 papillary RCC, (B) H&E 40 papillary RCC, (C) PAX positive, (D) AMACR positive.

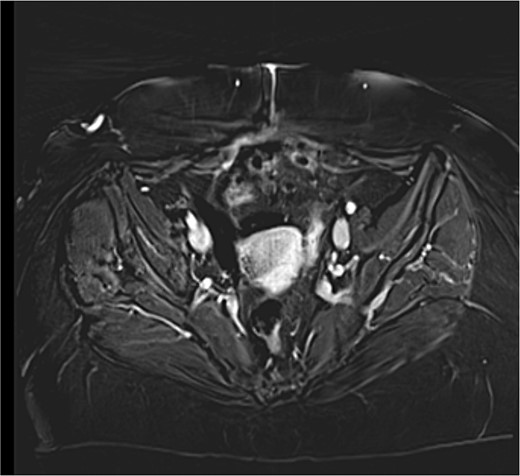

A close follow up was decided at the MTD meeting. Every 3 months a follow up MRI abdomen and CT thorax was performed in order to exclude recurrence. The patient is well and without evidence of recurrence 6 months after surgery (Fig. 3).

MRI T1 axial 3 months postoperative with no residual mass detected.

Discussion

Primary RCC in locations other than the native kidneys without any evidence of abnormality in both kidneys is referred as extrarenal. Extrarenal tissue is thought to originate from mesonephric remnants. There are three stages in fetal kidney development: pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros. Pronephros is the most immature form of the mammalian kidney and exerts no function. Mesonephros develops as an intermediate kidney phase, which on the 5th week of human gestation will form the metanephros. Metanephros will lead to the definite kidney as the former two disappear [7]. During this differentiation, some mesonephric structures may remain postnatally. These ectopic mesonephric cells may predispose to extrarenal RCC formation.

Primary extrarenal RCC is extremely rare with very few reports in the literature. Furthermore, there are only four cases associated with pRCC, three of which reported a type II pRCC like in our case (Table 1). Nunes et al. [1] presented a case of pRCC in the right adrenal gland which later metastasized to the left adrenal gland. Svirishou et al. [4] reported a paraaortic primary type II pRCC with multiple synchronous lymph node metastases, not amenable for upfront surgery and Li et al. [3] reported a retroperitoneal primary type II pRCC which was robotically excised. Sivaranjani et al. [8] reported the first synchronous primaries of adenocarcinoma of the rectum and extrarenal papillary RCC, with the last presenting as perinephric mass. In our case, the type II pRCC presented as a single pelvic mass.

| Author . | Year . | Location . | Presentation . | Management . | Histopathology . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. | 2019 | Right retroperitoneal mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Nunes et al. | 2019 | Right adrenal mass | Asymptomatic | EUS, Surgery | pRCC |

| Shrivisnou et al. | 2021 | Neck mass, paraaortic mass, multiple nodal metastases | Neck swelling | CT-guided biopsy, TKI palliative | pRCC type II |

| Sivaranjani et al. | 2023 | Right perinephric mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Our case | 2024 | Pelvic mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Author . | Year . | Location . | Presentation . | Management . | Histopathology . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. | 2019 | Right retroperitoneal mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Nunes et al. | 2019 | Right adrenal mass | Asymptomatic | EUS, Surgery | pRCC |

| Shrivisnou et al. | 2021 | Neck mass, paraaortic mass, multiple nodal metastases | Neck swelling | CT-guided biopsy, TKI palliative | pRCC type II |

| Sivaranjani et al. | 2023 | Right perinephric mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Our case | 2024 | Pelvic mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

EUS: endoscopic ultrasound, CT: computed tomography, pRCC: papillary renal cell carcinoma, TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

| Author . | Year . | Location . | Presentation . | Management . | Histopathology . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. | 2019 | Right retroperitoneal mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Nunes et al. | 2019 | Right adrenal mass | Asymptomatic | EUS, Surgery | pRCC |

| Shrivisnou et al. | 2021 | Neck mass, paraaortic mass, multiple nodal metastases | Neck swelling | CT-guided biopsy, TKI palliative | pRCC type II |

| Sivaranjani et al. | 2023 | Right perinephric mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Our case | 2024 | Pelvic mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Author . | Year . | Location . | Presentation . | Management . | Histopathology . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. | 2019 | Right retroperitoneal mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Nunes et al. | 2019 | Right adrenal mass | Asymptomatic | EUS, Surgery | pRCC |

| Shrivisnou et al. | 2021 | Neck mass, paraaortic mass, multiple nodal metastases | Neck swelling | CT-guided biopsy, TKI palliative | pRCC type II |

| Sivaranjani et al. | 2023 | Right perinephric mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

| Our case | 2024 | Pelvic mass | Asymptomatic | Surgery | pRCC type II |

EUS: endoscopic ultrasound, CT: computed tomography, pRCC: papillary renal cell carcinoma, TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Diagnosis of primary extrarenal RCC poses a challenge. There are no specific radiological features to contribute to such diagnosis, and in absence of an ectopic kidney or separate collecting system, the diagnostic suspicion is minimal. Consecutively, the diagnosis of extrarenal RCC is based on the postoperative histopathological features of the lesion. As in our case, postoperative pathological results established the diagnosis in the two reported cases of resectable pRCC [1, 3], while in the third inoperable case [4] a CT-guided biopsy was sufficient.

Histologically, pRCCs present a papillary, tubular, or tubopapillary growth pattern, composed by cells arranged on a delicate fibrovascularcore. The cytoplasm may be basophilic, eosinophilic, or sometimes partially clear [9]. Distinction between type I pRCC and type II pRCC is crucial since the latter is highly aggressive [10]. Nuclear grade, cytoplasmic volume, cytoplasmic granularity, and nuclear grooves are all cytomorphologic features that may aid in the distinction between type I pRCC and type II pRCC. Type I pRCC is characterized by low cuboidal epithelial cells with basophilic cytoplasm lining fibrovascular cores, most notably without pseudostratification, and usually with lower grade nuclei. In contrast, type II pRCC is characterized by the presence of pseudostratification of neoplastic epithelial cells with more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and higher grade nuclei [11]. In our case, pseudostratified layers of large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and typical nuclei with prominent nucleoli contributed to the diagnosis of type II pRCC.

Immunohistochemistry plays an important role in the diagnosis of an extrarenal RCC. The expression of RCC MA, CK7, AMACR, CD10, and PAX-8 not only establishes the diagnosis of RCC but also may assist in the sub-categorization into pRCC. PRCCs express CK7 and AMACR strongly while staining negative for CA IX and TFE3 [10]. Furthermore, EMA and PAX-8 are strongly expressed in pRCCs, CD10 and PAX-2 expression is average while C-Kit stain is negative [12, 13]. There are no major distinguishable immunochemical characteristics between type I and type II pRCC [12]. Although some studies report statistical significance in CK7 and EMA expression in type II pRCC [12], type II pRCC presents more heterogeneity. Definitely, there is a significant overlap in type I and type II pRCC immunohistochemical characteristics which makes their distinction complicated based on immunochemistry alone [12]. In our case, positive stain for CK7 and PAX-8 along with negative stain for C-Kit suggested strongly the presence of RCC. In combination with the histological characteristics of the tumor cells, the diagnosis of a type II pRCC was accomplished.

According to the NCCN guidelines, radical nephrectomy is considered the treatment of choice for localized papillary RCC. The role of adjuvant therapy in papillary RCC is still controversial. As there are not evidence-based guidelines for this rare entity, we followed the guidelines for primary RCC. In our case, the mass was completely resected with clear margins. The patient is under close follow up with MRI/CT every 3 months with no evidence of recurrence or metastasis 6 months after surgery.

In conclusion, primary extrarenal RCC is a rare entity. Since clinical and radiological features offer minimal diagnostic accuracy, histological and immunochemical examination of the tumor cells offer the definite diagnosis.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.