-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Evance Salvatory Rwomurushaka, Patrick Amsi, Jay Lodhia, Giant mesenteric lipoma in a pre-school child: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 11, November 2024, rjae698, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae698

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Lipomas are common benign tumors, typically affecting subcutaneous tissues in the head, neck, trunk, and upper limbs, particularly in individuals over 40 years old. However, visceral involvement, such as mesenteric lipomas, is exceedingly rare, with fewer than 50 pediatric cases reported in the English literature. Mesenteric lipomas are generally asymptomatic but may present with non-specific symptoms like abdominal distension or signs of partial or complete intestinal obstruction. Imaging modalities such as abdominal ultrasound and CT scan often reveal a well-differentiated fatty tumor, but histological confirmation is essential for diagnosis and management. We present a case of a 3-year-old female who experienced progressive abdominal distension over the course of a year. Imaging identified a large lipomatous tumor, which was surgically excised. Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of a mesenteric lipoma.

Introduction

Lipoma is a benign tumor arising from adipose tissue, typically enclosed in a fibrous capsule [1]. It is one of the most frequently encountered neoplasms in clinical practice [1, 2]. The prevalence of lipomas is estimated at ~1% of the population, with an incidence rate of ~2.1 per 1000 individuals annually [2, 3]. While most lipomas occur in adults aged 40 to 60 years, they commonly present in the cephalic regions of the body, such as the head, neck, shoulders, and back [2, 4–6].

In contrast, mesenteric lipomas are exceedingly rare, especially in pediatric patients. We present a rare case of a giant mesenteric lipoma in a 3-year-old child, highlighting the unusual presentation and surgical management of this condition.

Case presentation

A 3-year-old female child presented with a 1-year history of progressive abdominal distension. The distension was associated with loss of appetite and intermittent episodes of nausea, but no vomiting. There were no reported changes in bowel habits, yellowish discoloration of the eyes, or passage of black or bloody stools. The child had experienced unintentional weight loss, but there were no fevers or night sweats.

On examination, her vital signs showed a pulse rate of 138 beats per minute, oxygen saturation of 99% on room air, and a body temperature of 36.7°C. The abdomen was asymmetrically distended with a large swelling in the right lower quadrant, measuring ~17 cm by 15 cm. The mass was soft, mobile, and tender on deep palpation. There was no palpable organomegaly, and normal bowel sounds were heard on auscultation.

Baseline laboratory investigations revealed a hemoglobin level of 12.3 g/dl, a leukocyte count of 5.03 × 109/L, a platelet count of 341 × 109/L, serum creatinine at 22 μmol/L, blood urea nitrogen of 2.56 mmol/L, and liver enzymes within normal ranges.

An initial ultrasonography of the abdomen performed at a primary health facility identified a large intraabdominal mass with a hyperechoic texture. The origin of the mass was not clearly identifiable, and its size was difficult to measure due to its extensive nature.

A CT scan performed at the referring hospital revealed a low-fat density mass occupying the peritoneal cavity, measuring 8.8 cm × 16.5 cm, with features suggestive of a peritoneal teratoma versus peritoneal lipoma. Based on this, the child was scheduled for elective surgery.

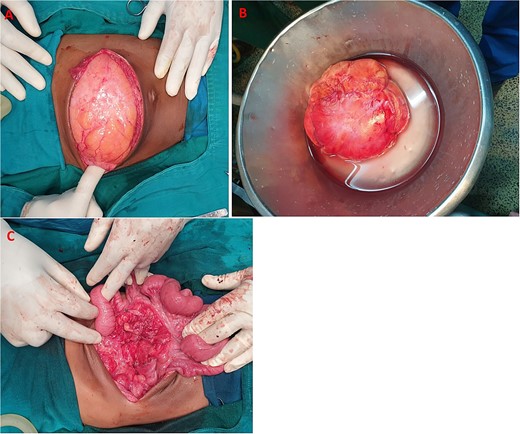

Intraoperatively, a lipomatous mass measuring 17 cm × 17 cm × 9 cm was found adherent to the small bowel, mesentery, and superior mesenteric artery. The mass was successfully resected via blunt dissection and sent for histopathological analysis (Fig. 1).

(A) Huge mesenteric lipoma, (B) lipoma excised whole, (C) cavity after excision of mesenteric lipoma.

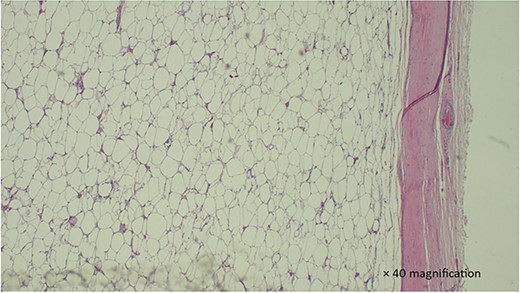

Histology revealed mature adipocytes without cytological atypia or separations, confirming the diagnosis of mesenteric lipoma (Fig. 2). The patient was discharged on the third postoperative day and had an uneventful recovery, with no abdominal symptoms reported during 8 months of follow-up.

H & E stained section show a section with proliferation of well-circumscribed mature adipocytes without atypia. which is well circumscribed.

Discussion

Despite the fact that lipomas are common, they rarely develop in the mesenteries of intestines [7]. While mesenteric lipomas have been commonly reported in children below three years of age, mesenteric lipomas are rare [7–9]. They are usually asymptomatic and encountered incidentally, however, non-specific symptoms such as painless progressive abdominal distension, anorexia, nausea, early satiety and constipation have been reported [5, 8]. Mesenteric lipomas may cause features of partial intestinal obstruction as a result of extramural compression on the intestines, or may cause a small bowel volvulus resulting in complete intestinal obstruction [5, 8]. Pressure symptoms resulting in early satiety and constipation are associated with malnutrition [10].

In our case, the baby had a slow growing tumor that presented with abdominal distension for about a year. It is obvious that this tumor was present and asymptomatic for sometime before the parents could notice the abdominal distension. This is consistent with the slow growth of the lipomas [7]. What patients describe as loss of appetite in this 3-year-old child may be a result of early satiety from pressure effect of the lipoma on the stomach. This is the common cause of malnutrition in children with mesenteric lipomas [10].

While larger masses may look more diffuse like in the case we are reporting, intra-abdominal lipomas are highly echogenic homogeneous masses enclosed in a capsule on abdominal ultrasonography. CT scan shows a circumscribed low fat density mass ranging from −120 to −65 HU [7, 10]. In this case, we arrived at the decision to operate and surgically excise the tumor based on CT scan results. While CT scan is more expensive and has risk of radiation for exposure, it characterized the tumor better than an abdominal ultrasound.

Surgical excision of mesenteric lipomas with an intact capsule either through laparotomy or laparoscopy is the most effective method with the lowest chances of recurrence [11, 12]. Recurrence has been reported in up to 5% of cases, possibly due to inadequate excision [12]. We managed to completely excise the tumor through a transverse incision in the abdomen. The option for open surgery was selected because of the tumor size.

The diagnosis of lipoma is confirmed by histopathological examination of the lipomatous tumor [5, 11]. It resembles normal adipose tissue under the microscope, with cytoplasmic lipid vacuoles laden mature fat cells of relatively uniform size, without cytological atypia [5]. Atypical and bizarre spindle cells and floret-like giant cells, with pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei, with a sclerotic background, are suggestive of the possibility of liposarcoma [5]. While fewer than 50 cases of mesenteric lipoma have been reported in English literature, mesenteric liposarcoma has not been reported [7].

Lipoblastoma, teratoma, lymphangioma, lymphoma, and neuroblastoma are relevant differential diagnoses in pediatric patients with a giant fatty mass in the abdomen [10]. In the case we are reporting, lipoblastoma would be considered a very close differential diagnosis based on clinical presentation and age of the patient. However, on histological examination of the fatty tumor, lipoblastomas are usually found to contain immature fat cells, called lipoblasts, arranged in lobules, with a myxoid background [9]. In our case, histology revealed mature adipocytes.

The prognosis of mesenteric lipomas is excellent because they are benign tumors, do not infiltrate the surrounding structures, and carry no potential for malignant transformation. Recurrence is low, especially if the tumor is excised completely with an intact capsule [2].

Conclusion

Mesenteric lipoma is a rare benign tumor in children, and though uncommon, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pediatric patients presenting with acute intestinal obstruction. Histological confirmation is essential to exclude malignancy and guide appropriate management.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient’s parent for permission to share her medical information to be used for educational purposes and publication.

Author contributions

E.S.R. and J.L. conceptualized and drafted the manuscript. P.A. analysed and reported histopathology slides and J.L. was the lead surgeon. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Funding

No funding or grant support.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parent for publication for this case report; additionally, accompanying images have been censored to ensure that the patient cannot be identified. A copy of the consent is available on record.