-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Arturs Niedritis, Sergejs Lebedjkovs, Massive anal condyloma lata following lung transplantation due to cystic fibrosis: successful treatment with circular hemorrhoidectomy with mucosal bridges, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 11, November 2024, rjae690, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae690

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This case report presents the treatment of a 36-year-old male patient with massive anal condyloma lata following lung transplantation due to cystic fibrosis. The patient, under long-term immunosuppressive therapy, developed extensive wart-like lesions around the anal canal. A modified circular hemorrhoidectomy with mucosal bridges was performed to excise the affected tissue while preserving functional integrity. The surgery, conducted under general anesthesia, successfully removed all lesions without complications. Postoperatively, the patient experienced no pain, bleeding, incontinence, or recurrence during follow-up. The preservation of mucosal bridges helped prevent common complications such as anal stenosis and mucosal ectropion. Histology confirmed the diagnosis of condyloma lata. This case underscores the effectiveness of circular hemorrhoidectomy, particularly in patients with circular anal canal lesions, and highlights the role of mucosal bridges in minimizing postoperative complications while ensuring complete lesion excision. This technique should be considered in similar cases of extensive anal lesions.

Introduction

Despite its effectiveness, the Whitehead procedure has historically been associated with significant complications, primarily due to the circumferential nature of the excision [1].

To mitigate these risks, the incorporation of mucosal bridges has been an important modification to the traditional technique. By leaving intact segments of anoderm and mucosa, mucosal bridges preserve some of the native tissue, thereby maintaining the functional integrity of the anal canal. Studies have demonstrated that by using mucosal bridges, postoperative complications such as stenosis can be significantly reduced, with a reported decrease in long-term sequelae [2, 3].

In patients with circumferential prolapse or extensive mucosal lesions, such as those observed in this case, circular hemorrhoidectomy offers a comprehensive solution by removing the entire prolapsed or diseased tissue, reducing the risk of recurrence that is higher with less aggressive procedures [1, 4].

This case report presents a patient with massive anal condyloma lata, who underwent prior lung transplantation due to cystic fibrosis, and was treated with a modified Whitehead hemorrhoidectomy involving mucosal bridges. The approach was chosen for its ability to manage extensive anal lesions in an immunocompromised patient, and reliably remove all of the affected mucosa.

Case presentation

The patient was a 36-year-old male who had undergone lung transplantation 5 years ago due to cystic fibrosis. After receiving immunosuppressive therapy, he began noticing painless lesions around the anal canal. The patient presented with wart-like lesions around and extending into the anal canal, ~1.5 cm from the linea dentata. These lesions caused the patient significant discomfort and slight bleeding, with minor pain, but without changes in the frequency, consistency, or caliber of bowel movements. The patient was referred to a surgeon after consulting a dermatologist.

The preoperative laboratory examination showed decreased leukocytes; all other values were within normal ranges. The patient underwent preoperative colon preparation using a laxative suppository (Microlax) three times. The procedure was performed by a board-certified senior general surgeon with 40 years of experience in colorectal surgery.

Due to the nature of these condylomatous masses, the chosen option was the circular hemorrhoidectomy technique, in order to remove all affected mucosa and prevent relapses. It was practically impossible to identify unaffected mucosa, so any other technique would have resulted in incomplete removal of the affected tissues. The operation was performed with the goal of maximally preserving unaffected tissue in the form of mucosal bridges to reduce the risk of complications.

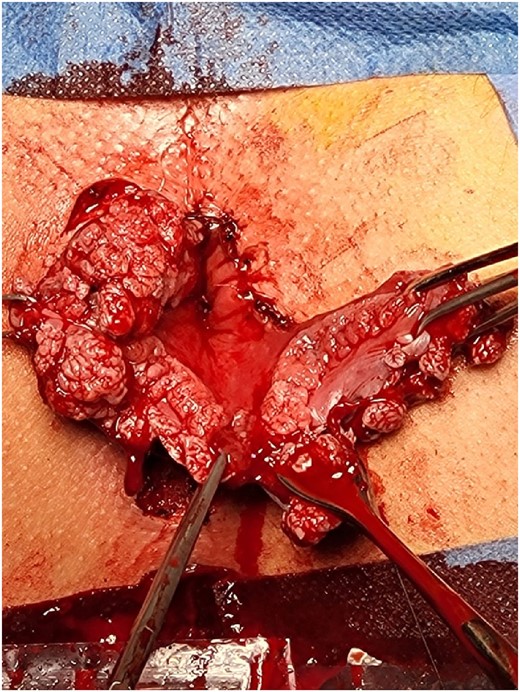

Anal dilation was performed using a 34 mm dilator for 10 minutes before incision to reduce hypertonicity of internal anal sphincter, to prevent stenosis and reduce post-operative pain. Operation time was 45 minutes under general anesthesia. Depth of lesions was assessed and a semi-circle incision was performed around the anal canal first on the right side (Fig. 1). Next blunt dissection and coagulation of bleeding tissues was performed to reliably visualize internal and external anal sphincter from there mucosa was dissected until no lesions were identified. The wounds were sutured radially by a simple interrupted suture, and the same technique was performed on the left side. It was possible to discern under the lesions several unaffected mucosal regions where mucosal bridges were left. The closure of the wounds was performed using a multifilament absorbable suture 3–0. There was neither residue of wart-like tissue nor bleeding was found during the evaluation after wound suturing (Fig. 2). The surgical wound was covered by a hemostatic sponge for the first 24 hours. After surgery, the patient was treated with intravenous analgesia for 12 hours and antibiotics for the first 24 hours, which were switched to the oral regimen the day after surgery. The patient was discharged on the first postoperative day. On short-term follow-up in the first, second and the fourth weeks, the patient reported no pain, no bleeding, no anal incontinence, nor recurrence of his previous complaints. In addition, anal stenosis and wound dehiscence was not found at the physical examination.

Beginning of the operation, massive wart-like masses with practically complete absence of healthy tissue.

Result immediately after operation. No pathological tissues remain.

The removed tissues were sent for histological identification and the result came positive for condyloma lata (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Despite the high reported incidence of complications following the operation, newer reports show that only ~5% patients experiencing sense of incomplete rectal emptying, 2.5% having anal incontinence in short-term, and 1.5% patients having mild to moderate anal strictures and 1% patients experiencing mucosal ectropion [5].

And reports revising the usage of Whitehead technique, report no significant difference in complications, for example, with Milligan–Morgan technique, and even patients who underwent Whitehead operation experienced less pain and showed less prolapse [6].

In this case, the use of circular hemorrhoidectomy with mucosal bridges resulted in excellent outcomes. The patient experienced a full recovery without major complications, and there was no recurrence of the anal condyloma lata, a common issue in immunocompromised patients. The preservation of mucosa through the use of mucosal bridges allowed for a more anatomically and functionally sound repair, reducing the risks of postoperative complications while ensuring the complete removal of diseased tissue. This demonstrates that circular hemorrhoidectomy, particularly with the mucosal bridge technique, remains one of the most effective surgical options for treating widespread anal mucosal lesions [2, 7].

It is important to mention that maximum relaxation needs to be achieved before starting the operation and during the operation, otherwise there is a substantial risk of tearing off the mucosa, which can lead to complications both post-operative and intra-operative.

It may be beneficial to review stance on this radical but effective technique once more, as many surgeons are currently not taught this technique and in situations like this other techniques may provide inadequate results.

In our experience there a total of three cases of similar condylomatous lesions we have treated with circular hemorrhoidectomy technique and when possible preserving mucosal bridges, all patients have had great results with no postoperative complications and minimal postoperative pain.

The reason why this technique is not used frequently is because of the high incidence of complications reported, however we agree that most complications were caused by misunderstanding the anal anatomy [5]. Many surgeons that experienced these severe complications excised the tissues at the white line, but not the dentate line [8].

The patient was recommended to return for follow-up visits at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months to monitor for any recurrence of lesions, afterwards the patient was recommended to attend screening for anal dysplasia. The patient was also recommended to receive the HPV vaccine to reduce the risk of recurrence of HPV-related lesions.

We recommend that all high-risk patients, including those with HIV and those who have undergone solid organ transplants, be referred for regular screening in accordance with the International Anal Neoplasia Society (IANS) 2024 guidelines. These guidelines emphasize the importance of early detection and monitoring for anal dysplasia, particularly High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), to prevent progression to anal cancer. Regular screening allows for timely intervention and improved outcomes in this vulnerable population [9].

In conclusion circumferential anal mucosa lesions may be considered as another absolute indication for circular hemorrhoidectomy.

Author contributions

A.N. formulated, reviewed and edited the original manuscript. S.L. supervised the case. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that this study had no funding source.

Declaration

All the authors declare that the information provided here is accurate to the best of our knowledge.

Consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity.

Ethical approval

Our institutional review board doesn’t require ethical approval for case reports.