-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Bailey D Lyttle, Kenneth Liechty, Kristine Corkum, Henry Galan, Nicholas Behrendt, Michael Zaretsky, Jennifer Bruny, S Christopher Derderian, In-utero gastric perforation from combined duodenal and esophageal atresia without consistent polyhydramnios, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 12, December 2021, rjab551, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab551

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a case in which prenatal imaging at 21-weeks’ gestation suggested duodenal atresia with a double-bubble sign and enlarged stomach. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging findings demonstrated dilation of the stomach and proximal duodenum favoring duodenal atresia but no indications of esophageal atresia. Subsequent prenatal imaging demonstrated interval spontaneous decompression of the stomach without the development of polyhydramnios, obscuring the diagnosis. Postnatally, initial abdominal radiography showed a gasless abdomen, and an oral gastric tube could not pass the mid-esophagus, raising concern for pure esophageal atresia. Intraoperative findings were consistent with duodenal atresia, pure esophageal atresia and a gastric perforation due to a closed obstruction. In this case report, we review the prenatal diagnostic challenges and the limited literature pertaining to this unique pathology.

INTRODUCTION

Duodenal atresia occurs in ~1 of 5000–10 000 live births and is associated with additional congenital anomalies in >50% of cases [1]. Esophageal atresia occurs at a rate of 1 in 2500 live births, 7% of which are pure esophageal atresia [2]. Concurrent duodenal and esophageal atresia is rare with few cases described in the literature [3–5]. Among those reported, specific prenatal imaging findings include the classic ‘double-bubble’ sign, gastric distention, polyhydramnios and a cystic thoracic structure consistent with a blind esophageal pouch [4, 5]. When duodenal and esophageal atresia present together, the diagnosis can be difficult given the alterations in expected sonographic findings [6]. Here, we present a case of a prenatally diagnosed duodenal atresia, postnatally diagnosed pure esophageal atresia and gastric perforation discovered intraoperatively.

CASE REPORT

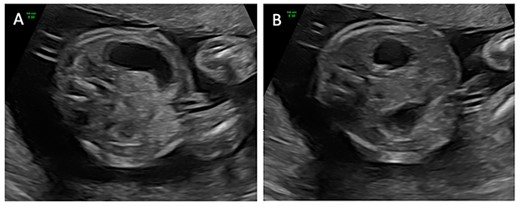

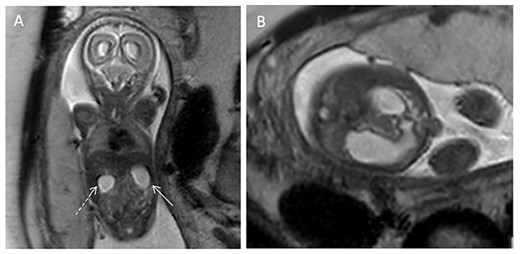

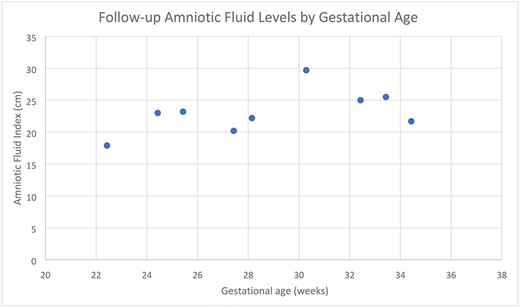

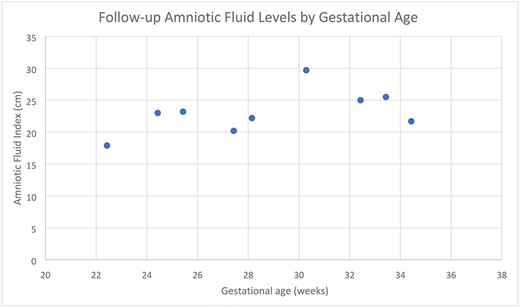

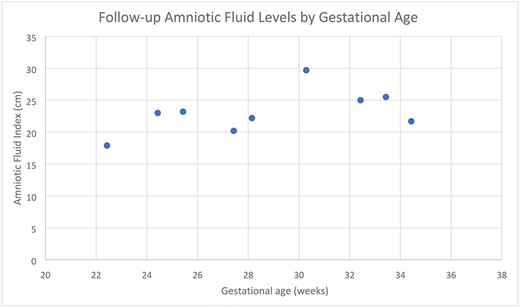

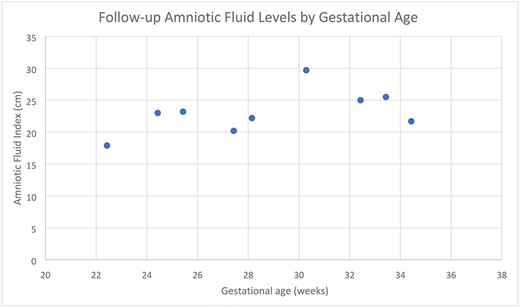

A 24-year-old G2P0010 woman was referred to our fetal care center at 21- and 2/7-weeks’ gestation following routine ultrasound that identified ascites, dilated small intestine and absent versus right-sided stomach. Fetal ultrasound performed at our institution demonstrated a dilated stomach with possible ‘double-bubble’ sign (Fig. 1). Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed dilation of the stomach and proximal duodenum without clear distinction between the two structures (Fig. 2), suspicious for duodenal atresia. Polyhydramnios was not seen on either ultrasound or MRI. She was scheduled for amniotic fluid index (AFI) evaluations (Table 1) and biophysical profiles (BPP) every 2 weeks with monthly growth ultrasounds, and induction was planned at 39-weeks’ gestation. At 30- and 2/7-weeks’ gestation, her AFI was mildly elevated at 29.7 cm (normal 5–25 cm). The ‘double-bubble’ sign was not identifiable on any follow-up evaluation. At 34- and 5/7-weeks’ gestation, she presented with decreased fetal movement. Her BPP was abnormal with absent fetal breathing episodes and a non-reactive non-stress test, necessitating further surveillance and ultimately Cesarean section. The infant was initially apneic, cyanotic without grimace and bradycardic. There was no response to continuous positive airway pressure ventilation requiring intubation with improvement in hemodynamic status. Oro-gastric sump tube placement was attempted but could not be advanced past the proximal esophagus. Radiographs noted coiling of the sump tube within the proximal esophagus and a gasless abdomen. On day of life two, the infant was taken to the operating room for rigid bronchoscopy and laparoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Bronchoscopy demonstrated normal tracheal and bronchial anatomy. The bronchoscope was used to evaluate the esophagus and confirmed a blind-ending esophageal pouch. A gastrostomy tube was placed laparoscopically without issue but upon insufflation of the stomach, froth was noted along the lesser curve just proximal to the pylorus. A supra-umbilical midline incision was made to further evaluate, and a gastric perforation was noted. A red rubber catheter was passed through the perforation and met obstruction within the second portion of the duodenum. The perforation was repaired, and a standard duodenoduodenostomy was performed.

Transverse ultrasound images obtained at 21- and 2/7-weeks’ gestation demonstrating a dilated stomach (A) with possible ‘double-bubble’ sign (B).

(A) T2-weighted coronal fetal MRI image demonstrating dilation of the stomach (solid arrow) and duodenum (dashed arrow). (B) T2-weighted transverse abdominal fetal MRI image demonstrating a dilated stomach in continuity with the dilated duodenum.

Amniotic Fluid Index measurements as recorded by ultrasound at surveillance follow-up appointments throughout the duration of pregnancy, demonstrating mild elevation to 29.7 cm at one appointment.

|

|

Amniotic Fluid Index measurements as recorded by ultrasound at surveillance follow-up appointments throughout the duration of pregnancy, demonstrating mild elevation to 29.7 cm at one appointment.

|

|

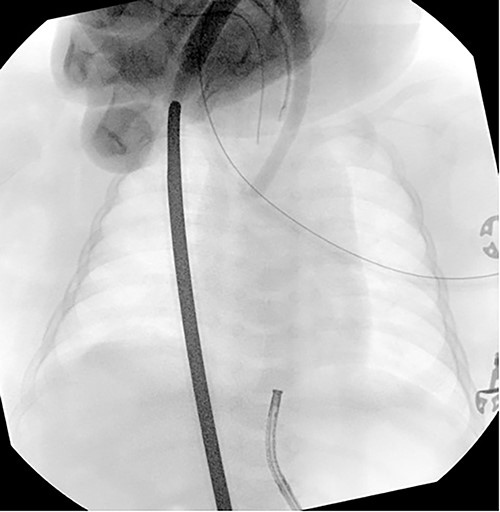

On day of life 15, an esophageal gap study was performed, which demonstrated a proximal esophageal pouch ending at the T2 vertebral level and a 7-mm distal esophageal stump, with an estimated esophageal gap of 6 cm (Fig. 3). The infant remained in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) awaiting long-gap esophageal atresia repair until 4 months of age when repeat esophageal gap study demonstrated a gap of approximately six vertebral bodies. He then underwent gastric pull-up, pyloroplasty and jejunostomy tube placement. Post-operative esophagram demonstrated no leak, and the infant was discharged home 3 weeks post-operatively with close follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Concomitant duodenal atresia and pure esophageal atresia is rare with limited cases reported in the literature, and prenatal diagnosis can be challenging. Duodenal atresia is characteristically identified on prenatal sonography by a ‘double-bubble’ sign, in which the stomach and proximal duodenum are dilated while the distal gastrointestinal tract remains decompressed. The diagnosis can be made prenatally in approximately half of cases [7]. Esophageal atresia is suspected prenatally when a small or absent gastric bubble is noted on prenatal ultrasound, though the sensitivity of ultrasound for esophageal atresia is only 42% [2]. The prenatal diagnoses of both duodenal and esophageal atresia are further suspected if polyhydramnios is also present [2, 7]. When duodenal and esophageal atresia occur together, a closed loop is formed involving the distal esophageal pouch, stomach and proximal duodenum. The stomach and proximal duodenum produce gastric secretions causing massive distension of the stomach and proximal duodenum. Estroff et al. describes three cases of concomitant duodenal and esophageal atresia, all of which presented with esophageal, gastric and duodenal distention in a characteristic dilated C-shaped structure within the abdomen [8]. However, in Estroff’s review of 10 additional cases, only 3 were diagnosed prenatally. In our patient, ultrasound findings were not consistent with those described by Estroff, though gastric dilation was present. Ethun et al. describes the use of fetal MRI to evaluate for esophageal atresia and cites a 78% positive predictive value with suggestive findings including polyhydramnios, small or absent gastric bubble and dilated esophageal pouch [9]. The study notes two cases in which duodenal atresia was also present and fetal MRI demonstrated dilation of the stomach and proximal duodenum in addition to the dilated esophageal pouch. In our patient, while there was appreciable dilation of the stomach and duodenum, there was no distinguishable esophageal pouch to suggest concomitant esophageal atresia.

Gastric perforation secondary to combined esophageal and duodenal atresia is extremely rare and seldom reported. In a recent literature review, Abou-Char et al. found only two cases of visceral rupture. In their own case, gastric wall rupture was noted on fetal MRI in one fetus of a monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy [4], and in Mitani et al., dilated structures noted on 26-weeks’ ultrasound were subsequently decompressed and associated with massive ascites 2 days later, suggesting enteric perforation [6]. Polyhydramnios was described in both cases and is an expected finding with in-utero gastrointestinal obstruction, making this case unique with intermittent and mildly elevated AFI. In summary, the complex prenatal presentation of concomitant duodenal and esophageal atresia makes diagnosis difficult, particularly without consistent polyhydramnios. By describing this case, we hope to raise provider awareness of this unique entity to help guide diagnosis and both pre- and post-natal management.

Esophageal gap study performed on day of life 15 demonstrating an estimated esophageal gap of ~6 cm.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

- pregnancy

- magnetic resonance imaging

- dilatation, pathologic

- esophageal atresia

- fetus

- intraoperative care

- polyhydramnios

- abdominal radiography

- abdomen

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- duodenum

- esophagus

- pathology

- prenatal care

- stomach

- congenital atresia of duodenum

- gastric ulcer perforation

- proximal duodenum

- gastric tube reconstruction

- double bubble sign

- stomach perforation