-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Siang Wei Gan, Reizal Mohd Rosli, George Kiroff, Abdullah Muhammad Rana, Darren Tonkin, Gas in gallbladder—gallstone ileus?, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 8, August 2019, rjz243, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz243

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gallstone ileus is an uncommon presentation among acute surgical patients. Its diagnosis is often delayed due to its non-specific clinical presentation. We report the case of an 81-year-old gentleman with a 2-day history of small bowel obstruction (SBO). He had a history of gallstone disease and no past surgical history. Plain abdominal radiography was consistent with SBO. A computed tomography (CT) abdomen scan would be warranted given the presentation of SBO in a virgin abdomen. However, this case emphasizes the importance of early CT imaging in a case of suspected gallstone ileus given that the diagnosis could not be made on plain abdominal radiography. CT abdomen is superior in detecting small amounts of gas and at discriminating soft tissue density.

INTRODUCTION

Gallstone ileus is a rare entity, occurring in 0.3–0.5% of patients with cholelithiasis [1]. It is the cause of acute small bowel obstruction (SBO) in only 1% of cases [2]. Treatment is often delayed due to delays in diagnosis. We present the diagnosis and management of a patient with acute SBO in a virgin abdomen.

CASE REPORT

An 81-year-old gentleman presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of vomiting, central abdominal pain and distension. He had no prior abdominal surgeries, but was waiting for an elective cholecystectomy for chronic cholecystitis. On examination, his abdomen was distended, with mild central abdominal tenderness and no evidence of umbilical or groin hernia. Blood tests were unremarkable except for mild acute kidney injury secondary to dehydration. His plain abdominal X-ray showed dilated small bowel loops (Fig. 1), consistent with a developed SBO. Given the scenario of SBO in a virgin abdomen, a computed tomography (CT) of abdomen was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of SBO with the transition point being at close proximity to the gallbladder.

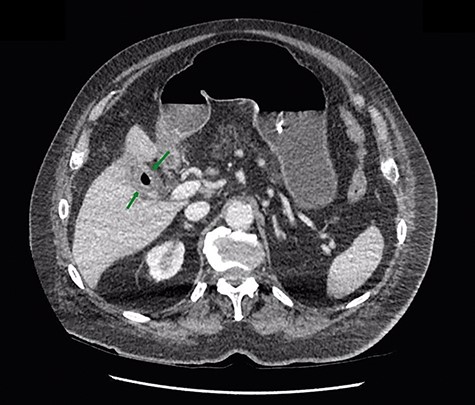

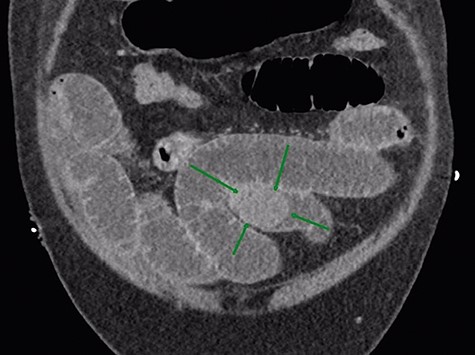

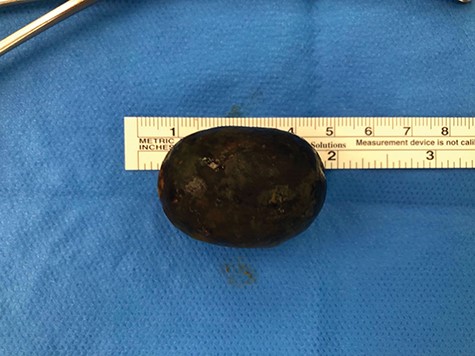

Given that the patient was clinically well, he was managed conservatively overnight with a nasogastric tube and intravenous fluid therapy. The CT scan was closely reviewed by the surgical team the following day and noted the presence of gas within the gallbladder, which was not commented upon by the radiologist (Fig. 2). Furthermore, SBO transition point appeared to be in the distal ileum, where a 3-cm “soft tissue” mass was seen (Fig. 3). His previous CT scan that diagnosed his chronic cholecystitis demonstrated a 3-cm gallstone within the gallbladder, which was not seen on the current CT. The findings of gas within the gallbladder in the setting of SBO and a mass of similar size to the known gallstone raised the suspicion for gallstone ileus. The patient then underwent a laparotomy and enterotomy for a 43-mm gallstone impacted in the distal ileum (Fig. 4). Apart from an episode of ileus, he made a full recovery post-operatively and was discharged home, with an outpatient follow-up in the surgical clinic.

DISCUSSION

Gallstone ileus refers to a mechanical bowel obstruction due to gallstone impaction within the bowel. Despite improvements in imaging techniques, it remains a diagnostic challenge and is associated with a high degree of morbidity and mortality [1]. The clinical presentation is usually non-specific, and 30% of patients have no known cholelithiasis [3]. Patients present with acute or subacute obstructive symptoms including nausea, vomiting, dehydration and abdominal distention or pain. A small proportion may present with haematemesis due to duodenal erosions [2]. The symptoms may be intermittent as the calculus tumbles through the intestine causing intermittent obstruction. There is often a delay in seeking medical attention, and a further delay in diagnosis and treatment [4].

Gallstone ileus occurs when a large gallstone erodes through the gallbladder wall as a result of inflammation and pressure necrosis into the small bowel via a cholecystoenteric fistula [2]. Cholecystoduodenal fistula is the most common fistula type occurring in about 70% of patients due to the proximity of the duodenum, while cholecystocolonic and cholecystoduodenocolonic fistulas account for 5%, respectively [1]. The majority of gallstones are impacted in the terminal ileum and ileocaecal valve due to narrow lumen and possibly less active peristalsis [2]. Larger gallstones are likely to be impacted in the proximal ileum or jejunum [1]. Less frequently, it may be impacted in the stomach, duodenum (causing Bouveret’s syndrome), Meckel’s diverticulum and colon [5].

Rigler’s triad in plain abdominal radiography of SBO, pneumobilia and ectopic gallstone within the bowel lumen is specific for gallstone ileus [6]. However, two out of three findings are seen in less than half of patients [5]. Pneumobilia occurs in 30–60% of patients but is non-specific and may be caused by an incompetent sphincter of Oddi or prior biliary procedures [7]. Moreover, only one-fifth of gallstones are calcified sufficiently to be visible on plain radiography [8]. Abdominal ultrasound can visualize the gallbladder, fistula or the absence of a previously visualized calculus in the gallbladder. The diagnostic sensitivity increases to 74% when both ultrasound and plain radiography are used [9].

In this scenario, this patient was known to have gallstones and a virgin abdomen, so gallstone ileus was always a possibility. It was the finding of gas in the gallbladder on CT that prompted the surgeons to consider the diagnosis. It is important to note that the diagnosis of gallstone ileus could not be made on plain abdominal radiography, despite the fact that the X-ray was consistent with SBO. This is due to very little air in the biliary tree and only a small bubble in the gallbladder. The gallstone was not calcified and appears of soft tissue density, and was invisible on plain X-ray. Therefore, CT abdomen should be the investigation of choice for suspected gallstone ileus, due to superior sensitivity of CT to detect small amount of gas within the biliary tree and to identify an intra-luminal foreign body of soft tissue density. Neither of these things is possible with plain radiology.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.