-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yuya Fujita, Manabu Kinoshita, Tomohiko Ozaki, Masanori Kitamura, Shin-ichi Nakatsuka, Yonehiro Kanemura, Haruhiko Kishima, Enlargement of papillary glioneuronal tumor in an adult after a follow-up period of 10 years: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 6, June 2018, rjy123, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy123

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Papillary glioneuronal tumor (PGNT) is a rare brain tumor grouped under mixed glioneuronal tumors according to the World Health Organization Classification of the Central Nervous System. The natural history of this pathology is not yet well documented. We report a case of PGNT that increased in size after a follow-up period of 10 years. An enlarged cyst wall and nodule showed a low intensity signal on T2*-weighted, suggesting hemorrhage during the clinical course. Characteristic pathological findings along with absence of BRAFV600E mutation identified the tumor as PGNT. The tumor characteristics of PGNT are discussed based on the presented case, with reference to the existing literature.

INTRODUCTION

Papillary glioneuronal tumor (PGNT) was first reported by Komori et al. [1]. In the WHO 2016, PGNT is classified as a neuronal and mixed neuronal–glial tumor [2]. Although MRI may demonstrate some characteristic findings which may suggest the possibility of a PGNT, the final diagnosis is only possible with histological evaluation, with immunohistochemistry playing an important role in the specific differentiation of such a lesion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) usually demonstrates a predominantly cystic lesion with a solid component, often in the periventricular region. A biphasic appearance is a pathological hallmark of this tumor, with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive glial cells surrounding hyalinized blood vessels. Neuronal cells are positive for synaptophysin and neuron-specific enolase and are present in pseudopapillary spaces or surrounding hyalinized blood vessels.

Some reports have described genetic alternations in PGNT, including MGMT methylation [3] and negative results for IDH1 and EGFR mutation [4]. BRAFV600E mutation in PGNT has not been described in the literature. SLC44A1-PRKCA fusion has recently been suggested as a specific genetic alteration for PGNT [5].

Due to the rare nature of these lesions, the natural history of PGNT still remains somewhat unclear. Although this tumor is considered benign (WHO grade I), in the present report we describe imaging progression of the lesion during a relatively long clinical course.

CASE REPORT

Clinical manifestations

MRI was performed for a 37-year-old Japanese man for diagnostic work-up for refractory headache. MRI showed a 10 mm cystic lesion with a mural nodule near the anterior horn of the right lateral ventricle.

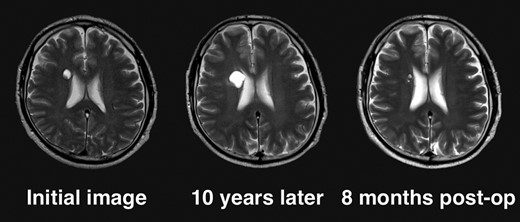

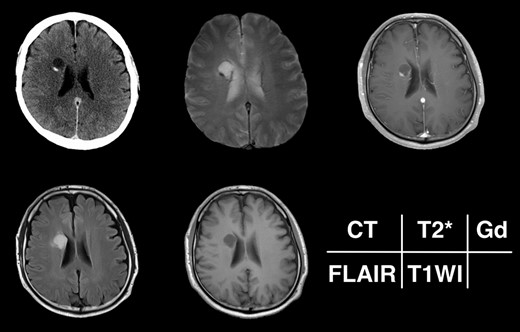

Given the absence of neurological symptoms, the patient was followed conservatively. After a follow-up period of 10 years, the lesion started to increase in size from 10 to 18 mm, accompanied by worsening of headaches. MRI revealed that the increased size of the lesion was attributable to an enlargement of the cystic component and the mural nodule (Fig. 1). A cystic mass with a gadolinium (Gd)-enhancing cyst wall and mural nodule were present. Signal intensity of the cystic component was high on T2-weighted imaging and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging. The cyst wall and nodule showed low signal intensity on T2*-weighted imaging (Fig. 2). Surgical removal was performed via a trans-cortical approach achieving gross total removal. The cystic component was covered with a transparent thin membrane containing clear yellow fluid, while the mural nodule comprised white, tough tumorous tissue. The lesion showed no invasion into the lateral ventricle. The postoperative course was uneventful, with no complications. No headache and no sign of recurrence have been seen, as of 13 months after surgery (Fig. 2).

Clinical course of the lesion on follow-up neuroimaging. The tumor increased in size during 10 years of follow-up. No recurrence has been seen as of 8 months postoperatively.

Radiological appearance of the lesion on CT and MRI. The lesion appears as a hypodense cyst with hyperdense nodules in the periventricular region on CT. Both the cystic wall and nodule show signal hypointensity on T2*-weighted images and Gd-enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images. The cyst is hyperintense on FLAIR and hypointense on T1-weighted images.

Pathological and genetic findings

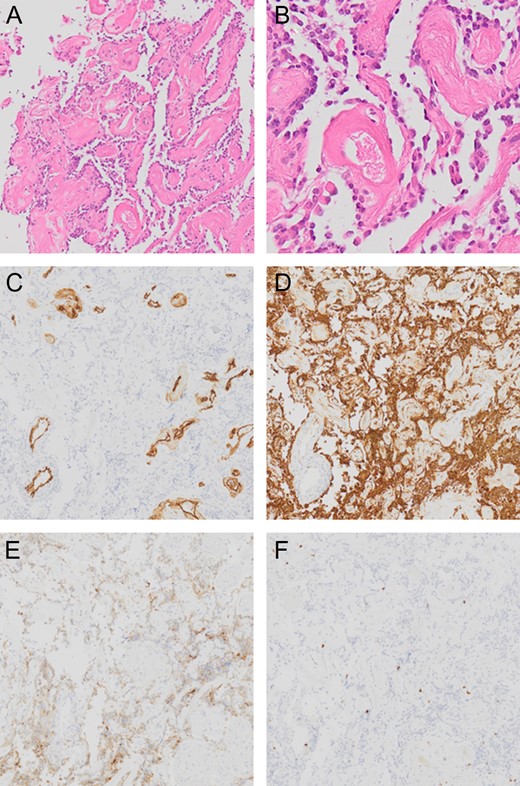

Tumor DNA was extracted from frozen tumor tissues using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan). The presence of hot spot mutations in IDH1(R132) and IDH2(R172) and at codon 600 of BRAF were analyzed by Sanger sequencing. The methylation status of the MGMT promoter was analyzed by pyrosequencing after bisulfite modification of genomic DNA from tumor specimens. A cutoff of MGMT promoter methylation was above 1.0%. The tumor showed a pseudopapillary structure comprising hyalinized blood vessels covered with a single layer of small, round cells (Fig. 3). These small round cells were GFAP-positive astrocytes and synaptophysin-positive neuronal cells, and the margin of the pseudopapillary structure displayed an acellular neuropil layer. Cellularity was moderate and no cellular atypia was evident. No mitotic activity or necrosis was noted and the Ki-67 (MIB-1)-labeling index was borderline for a WHO grade I tumor at 3%, which cautions the physicians to closely follow up the patient [6]. IDH1 was wildtype and IDH2 harbored a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (c.535-40G>A). No BRAFV600E mutation was detected and MGMT promoter was methylated.

Pathological presentation of the tumor. The pseudopapillary structure comprised hyalinized vessels (A and B) showing positive results for CD34 (C). Small, round cells surrounding these vessels are positive for GFAP (D). Although The neuronal cells between pseudopapillary are loose and hypocellular, in some regions, the synaptophysin-positive neuronal cells are seen in the interpapillary space (E). Ki-67 (MIB-1)-labeling index is 3% (F).

DISCUSSION

PGNT is thought to be clinically benign and slow-growing, corresponding to a WHO grade I tumor. Some patients could be discharged from neuro-oncological care after several years of imaging follow up after confirming stable condition of the lesion. The present case, however, may question this clinical attitude as the tumor did enlarge during its 10 years of clinical course and the Ki-67 (MIB-1)-labeling index was 3%, which could be considered as borderline. Close to a hundred cases have been reported in the English literature [4, 7, 8]. Mean age at diagnosis is 25.7 years (range: 4–75 years); 75% have been <30 years old [4, 7, 8]. The patient in the present case was relatively old compared to the mean age for this pathology and MIB-1 was borderline (3%) but the tumor was considered as a WHO grade I tumor as histological findings were compatible to WHO grade I PGNT. T2*-weighted images demonstrated a signal hypointense rim and nodule surrounding the cyst, suggesting the presence of calcification or hemorrhage that may have occurred at some stage during the clinical course. Xanthochromic cystic fluid observed during surgery and absence of calcification within the obtained surgical specimen supports the notion of the history of intratumoral hemorrhage during the clinical course. Buccoilero et al. [9] reported a 15-year-old girl harboring PGNT with a hemorrhagic onset, in which cavernous malformation was initially suspected, but progressive transformation of the hemorrhage cavity was subsequently demonstrated on CT and MRI. Pathological examination showed hemosiderin-laden macrophages and hemosiderin deposits surrounding the cystic lesion. These findings, combined with the experience of the present case, suggest that PGNT has the potential to bleed, leading to enlargement of the cystic component and nodule of the tumor. The rarity of PGNT poses a challenge to final diagnosis. Similar histological features can be seen in ganglioglioma with papillary features, making differentiation between these two pathologies difficult. There were no reports on PGNT patients with BRAFV600E mutation, which contrasts ganglioglioma with a 40% rate of BRAFV600E mutation [10]. Negative findings for BRAFV600E mutation in PGNT may help to distinguish this entity from ganglioglioma. Although DNA sequences for both IDH1 and IDH2 were examined, both were wildtype with a SNP for IDH2, implications of remain unclear. Further molecular characterization is required to elucidate the genetic nature of this disease.

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest regarding this report.