-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Erion Qaja, Mahalingam Sivakumar, Maryam Saleemi, An unusual case of massive hematemesis caused by aorto-esophageal fistula due to mycotic aneurysm of mid-thoracic aorta in a patient without prior aortic instrumentation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 5, May 2017, rjx084, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx084

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

In the words of Sir William Osler: “There is no disease more conducive to clinical humility than aneurysms of the aorta”. Here, we describe a case of a primary fistulous tract between a pseudoaneurysm sac and a portion of the mid thoracic esophagus leading to massive extravasation of blood causing hemorrhagic shock in a 71-year-old female.

INTRODUCTION

A primary aorto-esophageal fistula forms when an aortic aneurysm, true or false erodes into the thoracic esophagus. A secondary cause for aorto-esophageal fistula formation occurs as a complication following thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) [1].

‘Mycotic’ is the term used to describe an infected aneurysm irrespective of the cause. Cultures taken from mycotic aneurysmal sacs when positive must also clinically present with signs of infection such as leukocytosis and fever, before a diagnosis of mycotic aneurysm can be made.

Risk factors for mycotic aneurysm formation include endothelial damage as a result of atherosclerosis, antecedent infection such as endocarditis, pneumonia, cholecystitis, soft tissue infections, osteomyelitis, diverticulitis and urinary tract infection [2]. Iatrogenic arterial injury form subsequent percutaneous coronary intervention is another cause for mycotic aneurysm formation [3].

We report a case of a 71-year-old female of African American descent presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding found to have an aorto-esophageal fistula. Computed tomography scan was significant for a mid-thoracic pseudoaneurysm with active extravasation into esophagus. Sentinel bleeding in the esophageal lumen was also confirmed with esophagogastroduodenosopy (EGD). We present a case of successful endovascular treatment of a ruptured mycotic descending thoracic aorta that had fistulised into esophagus. TEVAR was performed using a Gore endoprosthesis stent graft without complication [4].

CASE REPORT

Our patient had a 4-month history of dysphagia with a 10–20 lb-weight loss and decreased appetite. Past medical history was significant for hypertension and alcohol abuse. On admission she was comatose, unresponsive and in hypovolemic shock, requiring intubation for airway protection.

On physical examination, there was noted to be a temperature of 36.5°C, heart rate of 120 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 88/60 (Class III hemorrhagic shock). Preliminary testing revealed hemoglobin of 8.0 g/dl, white cell count of 16.00 K/UL. Serum sodium of 127 mmol/l, lactate dehydrogenase was 553 U/L. Coagulation studies and liver function test were unremarkable. Blood cultures drawn were negative on two separate occasions. A portable bedside chest x-ray while patient was in Emergency Room showed a nonspecific mediastinal mass. Differential diagnosis given information at hand included but was not limited to bleeding gastric ulcer, thoracic aortic aneurysm, neoplasm and inflammatory process.

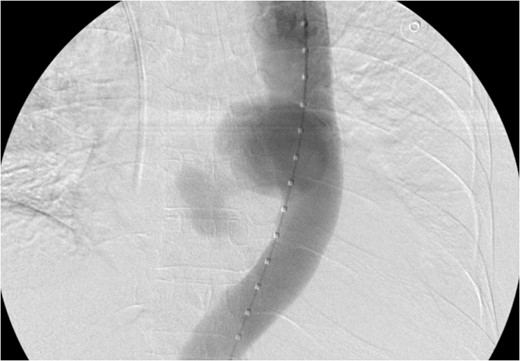

CT scan chest/abdomen/pelvis coronal view. Thoracic pseudoaneurysm distal to the left subclavian artery take off and proximal to the origin of the celiac artery.

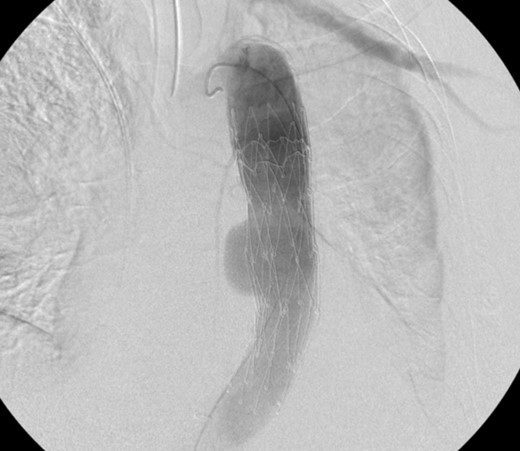

Pseudoaneruysm size, anatomical location (distal to aortic arch and above the celiac artery) made it feasible for TEVAR. In the operating room a right groin dissection was performed, stent graft was deployed through right femoral artery and postoperative fluoroscopy imaging showed exclusion of the sac with excellent contained flow within aortic lumen.

DISCUSSION

Epidemiologically, mycotic aneurysms have traditionally been attributed to endocarditis. One of the largest reviews reveals that 2.8% of 673 consecutive abdominal aneurysms (AAA) patients present with infectious aortitis as the etiology [5]. The disease is more devastating than traditional aneurysmal disease, with a large proportion of patients with mycotic aneurysm presenting for the first time with rupture.

The term mycotic is actually a misnomer for infectious aortitis since most aortic infections are not secondary to a fungal pathogen. Many organisms have been implicated with Staphylococcus aureus being the most common. Others include Streptococccus pneumoniae,Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Morganella morganii, Pasteurella multocida, and Salmonella species [6, 7]. Infections in native vessels are most commonly the result of seeding from a remote source or infections in an immunocompromised host.

Mycotic aneurysms of the thoracic aorta are rare but can be fatal if they are not diagnosed early. Thus, prompt index of suspicion, and appropriate imaging modality allows for timely intervention with avoidance of unwanted sequele. Diagnosis of infectious aortitis is often made late, adding to the complexity and imperilments of treating the disease. Patients may be younger, have evidence of remote infection, signs of systemic infectious process or may be immunocompromised. Initial signs and symptoms may be subtle including vague abdominal or back pain, nonspecific fevers, elevated white count and sepsis of unknown etiology [8].

Surgery with complete excision and debridement of infected tissue with in-line aortic reconstruction or extra-anatomic bypass [9] are the definite treatment for the hemodynamic stable patient with low cardiovascular risk profile. Advantages of open approach include the ability to appropriately wash out the mediastinum from contamination; however, the amount of inflammation could preclude one from placing a graft (Dacron or PTFE) to an already infected area. Lifelong prophylactic antibiotic therapy may be advisable to prevent recurrences unless there is a clearly identifiable and treatable source of infection.

Recently TEVAR has gained wide popularity due to the following reasons: minimally invasive nature of the procedure, faster control of bleeding, as well as significantly reduced operative time. In addition, most cases are diagnosed late, patient often times are profoundly anemic and hemodynamically unstable. Hence, most surgeons advocate TEVAR approach to the critically ill patient with impending massive exsanguination with or without temporizing balloon inflation device.

Aortogram showing successful deployment of covered stent graft.

TEVAR can be safely employed to treat an aorto-esophageal mycotic thoracic aneurysm when open repair is not possible because of patient’s comorbidity. Post-operatively our patient was asymptomatic and imaging demonstrated the stent graft in excellent position, without endoleak, and complete resolution of the aneurysm sac. Long-term follow-up is necessary for detection of endoleak, recurrence, or aneurysm propagation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None to declare.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the article. We certify that the submission is original work and has not been published previously elsewhere.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

SUPPORT

Nil.