-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David B. Hogarth, Paul M. Cheon, Javeed Kassam, Alexander E. Seal, Alexander G. Kavanagh, Penile necrosis secondary to purpura fulminans: a case report and review of literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 5, May 2017, rjx078, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx078

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

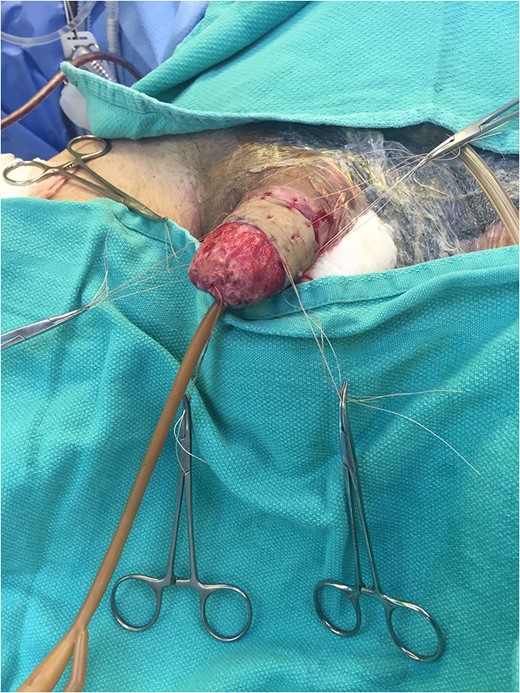

We report the case of a 60-year-old Hispanic male with widespread necrotic purpuric lesions involving the penile, suprapubic, inguinal and hip dermis due to purpura fulminans. Purpura fulminans describes a rare syndrome involving intravascular thrombosis and hemorrhagic infarction of the skin; this rapidly progressing syndrome features vascular collapse and disseminated intravascular coagulation. This patient’s penile necrosis involved the majority of the penile shaft and glans penis, and ultimately required partial glansectomy and repeated debridement for treatment. Subsequently, full thickness skin grafting was completed for reconstruction with good effect. While reports of penile necrosis secondary to various causes are documented in the literature, no prior reports describe penile necrosis secondary to purpura fulminans.

INTRODUCTION

Purpura fulminans is a hematological condition which involves both disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and skin necrosis [1]. There have been many reports of limb amputations as a result of purpura fulminans, but no such report for the involvement of the penis has been made [2–4]. We highlight a case of a 60-year-old male patient who presented with purpura fulminans secondary to idiopathic protein S deficiency, and subsequently underwent a partial glansectomy for necrosis of the penis.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old male presented to the emergency department with pre-syncope and general malaise, following a 6-day history of an enlarging erythematic lesion over his right hip. Past medical history was significant for a provoked posterior tibial deep vein thrombosis (DVT) 16 months prior treated with 6 months of warfarin, C3-C6 spinal fusion due to C4 ASIA D central spinal cord injury 22 months prior with significant neurologic recovery, and circumcision as a child.

DIC was diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings suggestive of coagulopathy plus abnormal coagulation parameters including a fibrinogen level <0.7 g/L and an INR in excess of 10. The patient’s hemoglobin was 64 g/L from a previously normal baseline, with associated thrombocytopenia. Multiple transfusions of packed red blood cells, platelets, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate over several days were required to stabilize the patient.

The patient was incidentally found to have right basilic and bilateral common femoral DVT’s on post-admission Days 8 and 12, respectively. Subsequently an IVC filter was inserted.

Excellent cosmetic and functional outcomes were obtained at 8 weeks of follow-up. The patient’s urinary and erectile function remained unchanged at follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Purpura fulminans is a hematological condition involving both DIC and necrosis of the skin [1]. It is characterized by widespread activation of the coagulation cascade, resulting in small-vessel thrombosis and the subsequent development of ischemia [2]. This manifests as erythematous macular lesions that develop central necrosis, becoming painful, blue-black and raised due to hemorrhage into the necrotic dermis [5]. These lesions can progress to necrosis of full-thickness skin or soft tissue [5].

The literature describes three forms of purpura fulminans based on causative mechanism: acute infectious, seen in association with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome; neonatal, which results from hereditary deficiency of protein C or S; and idiopathic, which usually follows a febrile illness and is thought to be mediated largely by protein S deficiency [6]. Each form is in turn associated with a particular clinical picture [6].

Much of the evidence on surgical management of purpura fulminans comes from studies of children with the acute infectious form of the disease, most often related to meningococcemia. Initial interventions in such patients are largely medical, aimed at resolving the inciting sepsis via antibiotic therapy [1]. However, early surgical consultation is important given the high incidence of compartment syndrome, and consequently limb loss, in these patients [3]. A retrospective review of nine patients with acute infectious purpura fulminans and evidence of compartment syndrome on early surgical exploration found a mortality rate of 44% (4/9), and in survivors, an amputation rate of 80% (4/5) [4]. The single patient avoiding amputation was diagnosed within 6 h of symptom onset, highlighting the importance of early treatment [4].

Interventions in compartment syndrome can include fasciotomy, which is typically effective in limb preservation if performed early in the disease course, ideally within 6 h of onset [1, 3]. However, there is less evidence for the effects of fasciotomy on skin necrosis [3].

As for debridement of necrotic skin, there is some controversy in the literature with regard to timing of intervention. In the absence of sufficient outcome studies to support one strategy over another, many postpone debridement until the necrosis has been fully demarcated, to avoid unnecessarily extensive surgical intervention [1]. Others prefer early debridement with the purpose of more effectively preventing wound infection, though there is no clear evidence to suggest that this prevents sepsis secondary to wound infection [1].

Penile necrosis is rare due to the extensive penile collateral blood circulation; case reports have documented penile necrosis secondary to severe atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus and vascular calcification associated with end-stage renal disease [7, 8].

A retrospective review of five patients who underwent partial penectomy due to penile gangrene and review of seven diabetic patients with penile gangrene showed that insufficient debridement may progress to liquefaction, wound infection, extensive tissue loss and sepsis [9]. Partial penectomy negatively impacts patients’ self-image and sex life and may induce anxiety and depression in few [10]. However, along with treatment of comorbid conditions, it may assist in prevention of wound liquefaction, preservation of penile length, and improvement of quality of life [9].

REFERENCES

Author notes

Please note, equal authorship between David Hogarth and Paul Cheon.