-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Siu Yan Amy Kok, Chung Ying Leung, Ki Yau Chow, An unusual cause of back pain: a case of large nonfunctioning retroperitoneal paraganglioma presented as a large cystic lesion. A case report and review of literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 4, April 2017, rjx059, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx059

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pheochromocytoma arising from outside the adrenal glands is also called paraganglioma. When it occurs below the diaphragm, in the organ of Zuckerkandl or retroperitoneum, it is also called extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma.

Paragangliomas are rare tumors which arise from neuroendocrine cells and extra-adrenal paragangliomas (EAPs) account for only 10–15% if all paragangliomas and may present incidentally as a symptomless mass. Typical triad of sweating, headache and fluctuating hypertension if not present makes preoperative diagnosis difficult. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Definitive diagnosis is usually made with histological findings. We report a case of large retroperitoneal tumor with size >10 cm which was a high risk depicting malignancy.

INTRODUCTION

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor of adrenal medulla. Pheochromocytoma arising outside the adrenal medulla is also called paraganglioma. These tumors arise from paraganglia of the autonomic nervous system, most commonly occurring in head and neck regions, and much less frequently in the retroperitoneum. But when they occur below the diaphragm in the organ of Zuckerkandl or retroperitoneum, they are called extra-adrenal paragangliomas (EAPs) [1]. Paragangliomas can be further divided into functioning and nonfunctioning based on their ability to secret hormones. Functional paragangliomas have shown to secret norepinephrine and nor-metanephrine resulting in clinical manifestations such as fluctuating or episodic hypertension, headache and sweating. Nonfunctioning paragangliomas are mostly asymptomatic and found incidentally as a mass. When nonfunctioning paraganglioma gets enlarged, it may present as abdominal pain secondary to compression of surrounding organs [2].

CASE REPORT

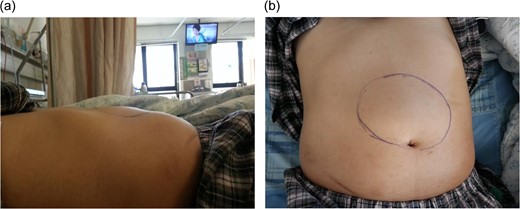

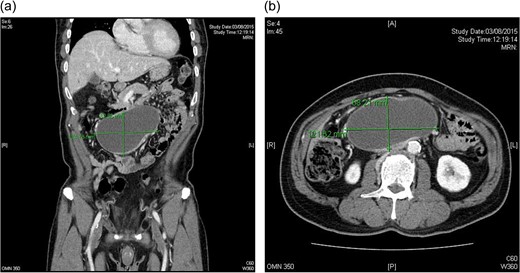

CT scan: 12.4 × 7.1 × 8.9 cm oval cystic lesion over central lower abdomen abutting loop of small bowel with compression on IVC, could represent a mesenteric cyst. No adrenal lesion (a and b).

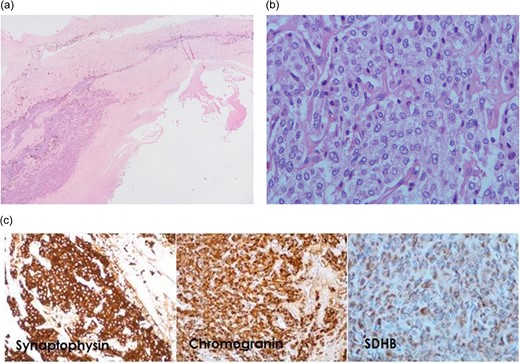

Microscopic examination. (a) The cyst wall shows mostly hypocellular fibrous tissue with tumor cells recognized in the relatively thicker portion (H&E ×20). (b) The tumor cells form nests surrounded by capillaries. They possess ample amount of amphophilic granular cytoplasm and roundish to slightly elongated nuclei with small nucleoli (H&E ×400). (c) The tumor cells are stained positive for neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin and chromogranin (×200). They are also positive for SDHB (×400).

The patient was referred to endocrine physician after operation. The 24-h urine for catecholamine was negative. Metaiodobenzylguanidine scan showed intact bilateral adrenal glands with normal secretion. Ultrasound thyroid and parathyroid was negative. The patient had uneventful recovery. He is currently symptom free after 1-year follow-up and is closely followed by physicians.

DISCUSSION

EAPs may arise in any portion of paraganglionic system though most commonly occur below the diaphragm, frequently in the organ of Zuckerkandl. The retroperitoneal paragangliomas arise from specialized neural crest cells distributed along aorta in association with sympathetic chain. EAPs have male preponderance and most commonly these patients present with headache, palpitation, sweating, vomiting and episode of paroxysmal hypertension. At times, they are asymptomatic or they present due to the compression of adjacent structures [3].

Paragangliomas can develop anywhere along the midline of the retroperitoneum. EAPs account for 10–15% of all adult paragangliomas with an incidence rate of 2–8 cases per million people per year. Age of onset is between 30 and 45 years with some literature suggesting male predominance. Clinically patients with a retroperitoneal paraganglioma often present with abdominal pain, back pain or a palpable mass. Only a subset of paragangliomas is clinically functional and often exhibit signs and symptoms consistent with active secretion of catecholamine, including headaches, sweating, palpitation and hypertension. This case represents a nonfunctional retroperitoneal paraganglioma presented as a large cystic lesion [1].

At gross examination, paragangliomas range from 1 to 6 cm in diameter, with malignant tumors tending to be slightly larger [4]. They are firm, encapsulated masses that adhere to adjacent structures. On cut section, paragangliomas are tan-red, with or without areas of necrosis. Microscopic analysis demonstrates neuroendocrine cells arranged in clusters called zellballen and interspersed with fibrovascular stroma. Functional tumors contain neurosecretory granules that give the tumor a granular appearance with silver stain. When catecholamine is oxidized by potassium dichromate solution, a dark brown staining results. Specific antibodies for neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin, chromogranin and S-100 protein may also be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Although paragangliomas are usually benign, 30–50% of all retroperitoneal paragangliomas are malignant. No definitive tests are currently available to differentiate between benign and malignant paragangliomas. Malignancy can often only be confirmed by detecting local invasion of surrounding structures upon examination at the time of resection or by detecting the presence of metastases. Furthermore, although histological and immunohistochemical findings do not permit a definitive diagnosis of malignancy, several factors have been associated with malignancy. These include a tumor weight >80 kg, high concentration of dopamine proximal to the tumor, tumor size >5 cm, the presence of confluent tumor necrosis and a younger patient age. In this case, tumor size >10 cm was a high risk depicting malignancy.

Genetic mutations within the SDHB and SDHD units are associated with increased risk for EAPs. It has also been reported that the incidence and prevalence of malignant paragangliomas are higher in patients with SDHB mutation. There is also an association between EAPs, gastrointestinal stromal tumor and pulmonary chondroma which is known as Carney’s triad.

Traditionally, the mainstay of treatment has been surgical removal. Chemotherapy has no defined role for the treatment of paragangliomas, but only is used in metastatic disease. Some cases use radiation therapy 4000–4500 cGy over 4–5 weeks for local control of these tumors [4]. Metastatic lesions have a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 36%. Because of malignant potential and higher recurrence rate in paragangliomas, lifelong follow-up is usually recommended [5].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.