-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Erika Bisgaard, Michael Tarakji, Frank Lau, Adam Riker, Neglected skin cancer in the elderly: a case of basosquamous cell carcinoma of the right shoulder, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 8, August 2016, rjw134, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw134

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Skin cancer remains the most common cancer worldwide, and basal cell carcinoma represents the largest portion of non-melanomatous skin cancers with over 3 million cases diagnosed annually. Locally advanced disease is frequently seen in the elderly posing clinical challenges regarding proper treatment.

We report on an 86-year-old female presenting with fatigue, anemia and a large ulcerated skin lesion along the right upper back. A biopsy of the lesion revealed a basosquamous cell carcinoma. She underwent a wide local excision with complex wound reconstruction.

Neglected skin cancers in the elderly can present difficult clinical scenarios. There are associated adjuvant therapies that should be considered following resection, such as local radiation therapy and other novel therapies. Newer therapies, such as with vismodegib, may also be considered. A comprehensive, multimodal approach to treatment should be considered in most cases of locally advanced, non-melanoma skin cancers.

Introduction

Non-melanomatous skin cancer is the most common cancer worldwide, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) representing the largest portion, with over 3 million cases diagnosed annually. Although it can occur anywhere, it most frequently occurs in areas with excessive sun exposure such as the head and neck [1]. A total of one-third of BCC is due to neglect. Factors including social isolation, skin changes and multiple medical co-morbidities, leave elderly patients at high risk of neglecting potentially malignant skin cancers causing them to progress to advanced stages [2].

Case Report

This patient is an 86-year-old female who presented with a hemoglobin of 6.6 gm/dl at her annual physical. She was sent immediately to the emergency room (ER) for further work-up. At the time of her admission, her only complaint was progressive fatigue over the past several months.

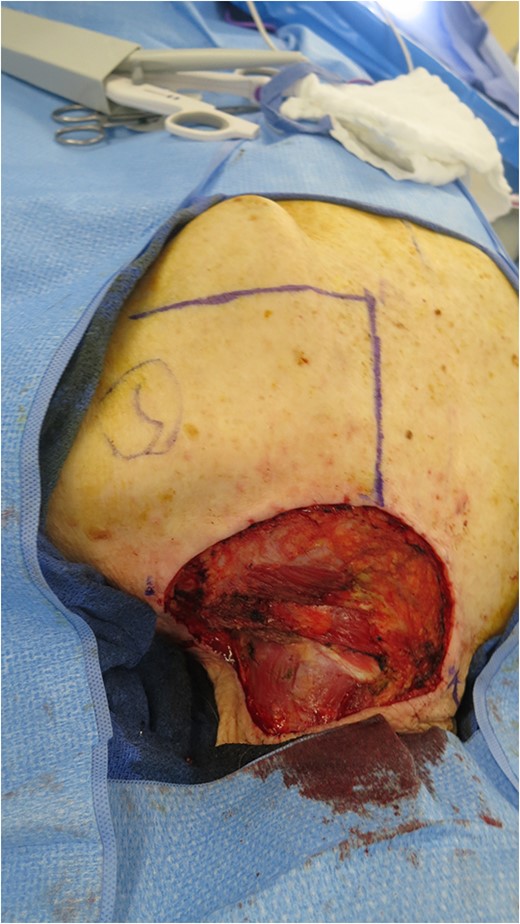

On physical examination, a fungated, ulcerated 7 × 6.5 cm lesion on the right shoulder was noted (Fig. 1). In the ER her hemoglobin and hematocrit was found to be 7.0 and 23.9 gm/dl. On further questioning, she admitted to hiding this skin lesion for months, possibly much longer, due to her husband's poor health and not wanting to ‘bother’ others in her family with this issue. The patient noted she had the mass for at least 6 months and it had increased in size and bled easily.

Original 7 × 6.5 cm fungated, ulcerate lesion of the right shoulder.

On admission, she received two units of packed red blood cells and responded appropriately with a hemoglobin of 9.3 gm/dl. Plastic surgery performed a shave biopsy of the lesion, and final pathology revealed a basosquamous carcinoma. She was evaluated by surgical oncology and an operative plan of wide local excision with subsequent complex wound reconstruction was discussed. The lesion was excised with 1-cm circumferential margins down to the muscle layer. The residual defect measured 11 × 10 cm extending from the base of the neck to the spine to the scapula (Fig. 2). A rhomboid flap was created and rotated to fill the defect that was closed in two layers. The defect and rhomboid flap totaled an area of 220 cm2 (Fig. 3).

Open defect measuring 11 × 10 cm after excision of primary lesion.

Primary closure of defect with rhomboid flap, total area of 220 cm2.

Six-week post-operative lesion after two weeks of radiation treatments.

The final pathology showed a focally positive microscopic deep margin involving the muscle layer.

Discussion

The standard of care for BCC depends on timing of diagnosis and extent of disease. Superficial BCC is managed non-surgically with topical therapies like imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil. These therapies provide local control and reduced rates of recurrence [3]. In advanced lesions, treatment involves surgical excision with primary wound closure. However, larger lesions requiring complex surgical procedure and reconstruction are often accompanied by adjuvant radiation therapy [4]. As in this case, the best approach to gain locoregional control is the combined approach of wide excision with 5-mm margins followed by adjuvant radiation therapy (Fig. 4).

Combined approaches have resulted in impressive 5-year cure rates of ~95%. However, certain lesions are more likely to recur, such as lesions with a large diameter or those located along the head and neck and periorbital region. Finally, incomplete excision, or focally involved margins, as in this case, often requires additional procedures or adjuvant radiation therapy [5].

Radiation therapy as a primary treatment is reserved for patients who do not wish to undergo an operation or are deemed high-risk surgical patients due to co-morbidities. There is a reported cure rate of 91–93% with radiation therapy alone, slightly lower than that for primary surgical excision. Radiation therapy is best utilized for early, small-diameter lesions, with a few side effects such as erythema, skin breakdown, edema and infection. Long-term effects of radiotherapy are severe in some cases, resulting in skin and soft tissue changes and potential necrosis [6].

Recent research demonstrates the role of certain genes in the carcinogenesis of BCC, mainly activation of the patch-1 gene (PTCH1). This 12-transmembrane receptor protein on epidermal cells is a part of the hedgehog signaling pathway. Activation of this receptor inhibits the smoothened (SMO) gene, which codes for a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) involved in the regulation of the cell cycle. Wrongful activation of the PTCH1 transmembrane receptor leads to dis-inhibition of the SMO gene resulting in the production of the protein and its movement into the cell membrane.

This GPCR activates hedgehog signaling genes causing cell replication through activation of the GLP1 oncogene. Usually, this hedgehog pathway is quiescent in adults via in vivo feedback mechanisms that antagonize the PTCH1 to prevent hedgehog binding and transduction of cell proliferation signals. These mechanisms have been harnessed to develop the newest treatment modality for BCC, vismodegib [7].

Vismodegib is a small molecule inhibitor approved by the Federal Drug Administration in 2012 for treatment of advanced, unresectable BCC. It is an oral medication for metastatic BCC, local recurrence after an initial operation and patients who are not candidates for surgery or radiation. A phase-1 trial showed a 58% response to vismodegib with minimal adverse effects including muscle spasm, fatigue, alopecia, dysguesia and nausea [8]. The ERIVANCE BCC trial showed an objective response rate of 30% in metastatic BCC and 43% in locally advanced BCC and ultimately showed vismodegib to be an effective option for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic BCC [9].

These trials suggest that this drug may provide a viable option for the treatment of previously untreatable BCC without risk of a potentially disfiguring surgery. Recent studies suggest a combination therapy with radiation and vismodegib could be even more effective for the treatment of advanced disease [10]. However, in our case, consideration should be given to all potential treatment options, accounting for the overall health of patient and after a detailed discussion of risks and benefits of each treatment approach.

Neglected skin cancers in the elderly present a potentially difficult clinical scenario with multiple treatment options. Traditionally, lesions are excised with adequate margins; however, in cases of advanced, wide-diameter disease, evidence suggests that the addition of radiation therapy has beneficial effects upon long-term outcomes. Vismodegib, a newly approved drug for the treatment of advanced, non-resectable BCC, can be considered in certain circumstances. Combination therapies including surgical excision with local radiation therapy remain the mainstay of treatment whenever feasible.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.