-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ruj Nana, Porntita Sae-Li, Juthamas Hannarong, Kan Witoonchart, When stroke uncovers a hidden cardiac mass: LVOT papillary fibroelastoma in an elderly Thai male, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf663, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf663

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Papillary fibroelastoma (PFE) is a rare, benign cardiac tumor usually arising from the heart valves, whereas non-valvular involvement is uncommon. We report herein a case of a 71-year-old Asian male who developed an ischemic stroke during hospitalization for gastrointestinal bleeding. A stroke workup led to the incidental detection of a cardiac mass in the left ventricular outflow tract, later confirmed as PFE following surgical excision without complications. This case highlights the importance of cardiac imaging in patients with cryptogenic stroke and supports early surgical excision to prevent recurrent embolic events.

Introduction

Papillary fibroelastoma (PFE) is one of the most common primary cardiac tumors, accounting for ~7%–10% of all primary cardiac neoplasms [1, 2]. While PFEs predominantly occur on heart valves at 82%, non-valvular involvement is uncommon, especially at the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT), which accounts for 9% of reported cases [3]. This case report describes a presentation of a non-valvular PFE arising in the LVOT, discovered incidentally during workup for an acute ischemic stroke in a patient without conventional embolic risk factors. The case highlights the importance of cardiac imaging in patients with unexplained embolic events and supports early surgical management to prevent recurrence.

Case description

A 71-year-old Asian male with hypertension and dyslipidemia presented with lower gastrointestinal bleeding, which was managed promptly. During hospitalization, he developed acute left homonymous hemianopia. His sensory and motor function were normal. Initial investigations and management were performed at the local hospital before referral to our institution.

A non-contrast computed tomography brain revealed an acute infarction in the right posterior cerebral artery territory. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed no evidence of atrial fibrillation. A transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was requested by the neurology team to rule out cardioembolic causes of the stroke. The TTE demonstrated preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 80% and no thrombus. However, it revealed a heterogeneous, hypermobile mass with a stalk measuring 1.45 × 1.04 cm located at the LVOT.

A preliminary diagnosis of infective endocarditis was made based on the TTE findings. Antibiotic regimens were administered by the local hospital: ceftriaxone 2 g intravenously once daily and ampicillin 3 g every 6 h. Aspirin and statins were prescribed as part of risk modification for stroke.

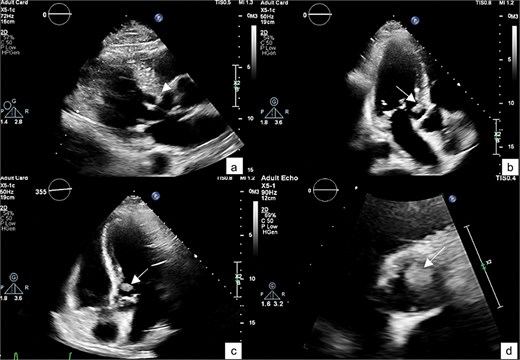

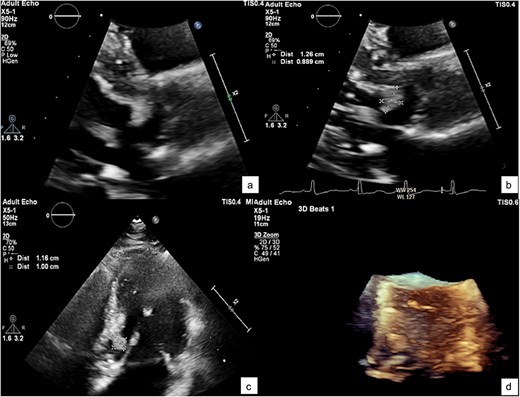

He was referred to our hospital for further evaluation by the cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery departments. On admission, he was afebrile with a heart rate of 62 beats per minute, blood pressure of 148/73 mmHg, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute. No abnormalities were noted in any other system. Laboratory findings were unremarkable. An ECG demonstrated normal sinus rhythm. TTE re-evaluation revealed a normal LVEF of 72% with a 1.2 × 1 cm hypermobile cardiac mass attached to the basal anteroseptal wall near the LVOT without evidence of LVOT obstruction; there were no valvular lesions or thrombus seen (Figs 1 and 2). Coronary angiography showed normal coronary vessels. Due to its nature and clinical presentation, the patient was set for early surgical excision of the mass 3 days after admission.

A TTE showing a small-rounded mass attached to the LV septum (arrow), which can be seen protruding into the LVOT in various echocardiographic views: Parasternal view (a), parasternal long axis view (b), 5-chamber view (c), and short-axis view of aortic valve (d).

A zoomed-in view of the mass with measurements of 1.2 × 1 × 0.9 cm (a–c) and in 3D echocardiography (d).

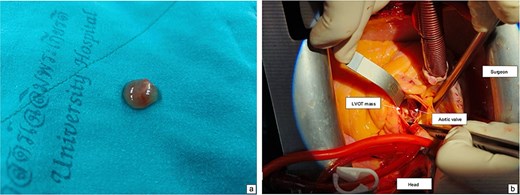

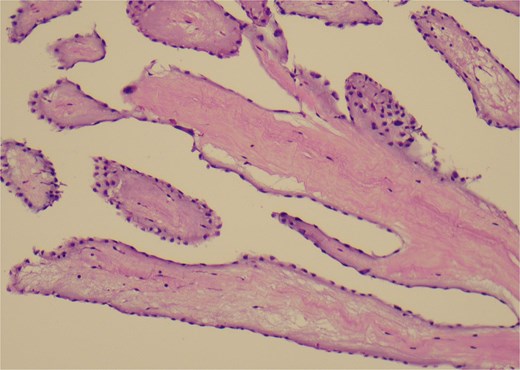

The patient underwent surgical excision of the LVOT mass via a median sternotomy. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CBP) was established using arterial cannulation in the ascending aorta and single, two-stage venous cannulation via the right atrium. An oblique aortotomy was performed to access the LVOT, and the mass was completely excised. The aorta was closed with 4–0 Prolene, and the excision site was inspected to ensure no residual tissue. Hemostasis was achieved, and CBP was weaned off once adequate cardiac function was confirmed. Two tube drainages in pericardial and mediastinal spaces. The pericardium was closed, with a total CBP time of 45 min, an aortic cross-clamp time of 27 min, and a total operative time of 3 h and 12 min. Gross pathology showed a 1 × 1 × 0.3 cm irregular, soft, grey-white polypoid mass. Histology examination of the mass revealed multiple branching papillary fronds with a central avascular collagen, lined by a layer of hyperplastic epithelial cells, consistent with papillary fibroelastoma (Figs 3 and 4).

Intraoperative view showing mass attached to the left ventricular outflow tract (a). A gross specimen of the excised mass (b).

A histological view of the excised mass reveals elongated and branching papillary fronds with central avascular collagen, lined by hyperplastic epithelial cells.

The postoperative course was uneventful. However, the patient’s vision remained impaired with persistent blurring. He was discharged five days after the surgery without antithrombotic medication. A follow-up appointment with the thoracic surgery department was scheduled in two weeks. At the visit, he was clinically stable, with no chest pain, dyspnea, orthopnea, dizziness, or gastrointestinal bleeding, although blurred vision persisted.

Discussion

The clinical presentation of PFE is various, from a benign accidental finding to a serious cardioembolic complication, such as stroke or transient ischemic attacks, which occur in 34%–53% of symptomatic cases [1, 3, 4]. Our patient developed a left homonymous hemianopia, which prompted further stroke evaluation, resulting in the incidental identification of a hypermobile cardiac mass in the LVOT during TTE. The tumor’s embolic potential was raised by its mobility and location, which indicated that urgent surgical excision was necessary to prevent further cerebrovascular accidents.

The differential diagnosis for a cardiac mass includes infective endocarditis, thrombus, primary tumors, and metastatic tumors. The echocardiographic findings of a small, mobile, pedunculated mass were indicative of PFE; the diagnosis was subsequently confirmed histologically. LVOT PFEs, despite their rarity, present a significant embolic risk due to their proximity to systemic circulation. In our case, the patient’s embolic stroke probably resulted from tumor fragments dislodging from the LVOT mass. Surgical excision was done as prior studies demonstrated that removal of papillary fibroelastomas reduces the risk of recurrent embolic events [5].

A similar case was reported by Coats et al. [6], in which a 70-year-old female presented with incidental findings of LVOT papillary fibroelastoma and a history of previous transient ischemic attacks. Burri [7] also reported a 41-year-old woman who had suffered an ischemic stroke caused by a secondary embolic event from an aortic valve papillary fibroelastoma. Similarly, neither case has a history of atrial fibrillation or any other significant embolic risk factors. The diagnoses were raised following a routine stroke investigation that included an echocardiogram. All cases reinforced the importance of cardiac imaging in cryptogenic stroke, particularly in patients without conventional embolic risk factors. The rapid detection and surgical removal of the tumor prevented further embolic complications in this instance, highlighting the clinical suspicion in similar scenarios.

Conclusion

This case highlights the ischemic stroke presentation of papillary fibroelastoma, the importance of differentiating it from other cardiac masses, and the potential for embolic complications, particularly in tumors located in the LVOT. Early recognition, accurate diagnosis through echocardiography, and timely surgical intervention are essential in preventing life-threatening events associated with this rare but clinically significant cardiac tumor.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the nursing and physician team for their dedicated care of the patients.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Funding

None declared.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication.