-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nhan T Vu, Hoang Tran Viet, Hung Van Tran, Nhan H N Pham, Linh TNU, A case series on the outcomes of laparoscopic pull-through surgery combined with Swenson-like technique and intraoperative frozen section biopsy for Hirschsprung’s disease in children, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf451, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf451

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The combination of laparoscopic pull-through surgery with intraoperative frozen section biopsy has emerged as a promising approach in the treatment of Hirschsprung's disease. This case-series report study aims to describe the short-term outcomes. All patients who underwent one-stage laparoscopic pull-through surgery combined with the Swenson-like technique at the General Surgery Department of Children’s Hospital No. 2. We conducted 19 patients. The mean surgery duration was 143.6 ± 42.5 min. The mean postoperative hospital stay was 11.2 ± 3.7 days, with no intraoperative complications. Postoperatively, 4/19 cases (21.1%) had small bowel-colon inflammation, and 2/19 (10.5%) had perianal dermatitis. The mean follow-up time was 18.1 ± 4.1 months, with 4/19 (21.1%) patients experiencing small bowel-colon inflammation. No patient developed constipation. Short-term follow-up results for children undergoing surgery in this study were relatively good, with few complications. It is safe and feasible for treating classic Hirschsprung disease in children.

Introduction

Hirschsprung's disease is characterized by the congenital absence of ganglion cells in the enteric nervous system of the distal gastrointestinal tract, with the aganglionic segment varying in length as it extends upward. The affected bowel segment lacks peristalsis, causing frequent spasms in the proximal bowel, which still retains feces and gas. This leads to gradual dilation of the upper bowel, resulting in a clinical picture of intestinal obstruction. The prolonged fecal accumulation can lead to “fecal intoxication,” malnutrition, developmental delays, and in severe cases, life-threatening complications such as colonic perforation and small bowel-colon inflammation. Therefore, early surgical intervention is necessary for these patients [1, 2].

Laparoscopic surgery is a minimally invasive approach that still preserves the benefits of open surgery, and it is increasingly being applied in the treatment of Hirschsprung's disease [3, 4]. Laparoscopic surgery allows the surgeon to clearly visualize the entire colon to identify the aganglionic segment, transition zone, dilated segment, and healthy colon before mobilizing the colon. This helps reduce the time spent on anal dissection during the mesenteric vascular ligation phase and ensures that the bowel segment being pulled down is not tense or twisted. As a result, laparoscopic surgery is associated with fewer complications compared to traditional transanal resection. However, studies on laparoscopic surgery for treating classic Hirschsprung’s disease in children in Vietnam are limited [5, 6]. Therefore, we conducted this study with the aim of evaluating the outcomes of laparoscopic pull-through surgery combined with the Swenson-like technique in the treatment of Hirschsprung's disease in children.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study was designed as a case-series report. All pediatric patients under 16 years old with a confirmed diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease at Children’s Hospital no 2 by histology from December 2022 to June 2024 (via suction biopsy), who underwent one-stage laparoscopic pull-through surgery combined with the Swenson-like technique and frozen section biopsy to identify the anastomotic site were included in the study. We excluded children with Hirschsprung's disease and a temporary stoma, those who had previous anorectal surgery (except rectal biopsy), those with an aganglionic segment beyond the sigmoid colon, and those with follow-up ˂6 months post-surgery. The demographics data including age and sex were also recorded at recruitment. We recorded surgical details such as operation time, blood loss, and intraoperative complications, along with postoperative outcomes including hospital stay, complications, and follow-up results at 6 months post-surgery.

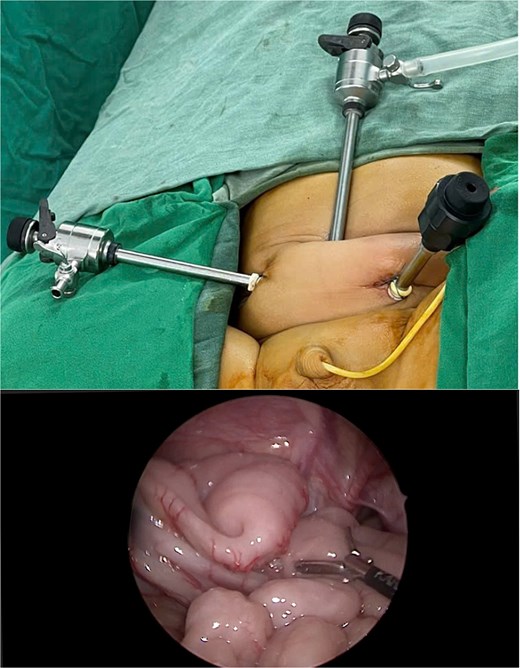

All patients had a preoperative mechanical bowel preparation and a gradually reduced fiber diet 3 days before surgery. The surgeries were performed by a team of experienced pediatric surgeons, each with over 10 years of experience in pediatric colorectal surgery. To ensure consistency, a standardized surgical protocol was followed for all cases, with all surgeons performing the laparoscopic pull-through combined with the Swenson-like technique and intraoperative frozen section biopsy. Firstly, the patient is positioned in a gynecological posture, under general anesthesia combined with caudal block. Three trocars are inserted through the abdominal wall: a 5 mm trocar at the umbilicus (for the camera), and two 3 mm or 5 mm trocars at the left flank and the right subcostal region (for surgery) (Fig. 1).

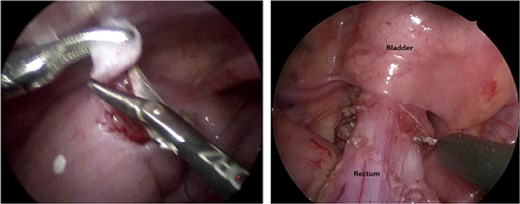

The CO2 insufflation pressure in the abdominal cavity is maintained at ⁓8 mmHg. The entire colon is observed to identify the lymph node-negative segments, dilated sections, and healthy portions. A frozen section biopsy is performed with a full-thickness bowel sample to identify lymph nodes within the segment of the bowel. While awaiting the results of the frozen section, dissection, and mobilization are carried out, along with the ligation of the mesenteric vessels of the colon and rectum. Dissection is performed close to the rectal wall, extending to the lower pelvic cavity, 2 cm anterior to the peritoneal fold, and posteriorly at the level of the sacrum (Fig. 2).

Frozen section biopsy and dissection of the sigmoid colon and rectum down to the pelvic cavity.

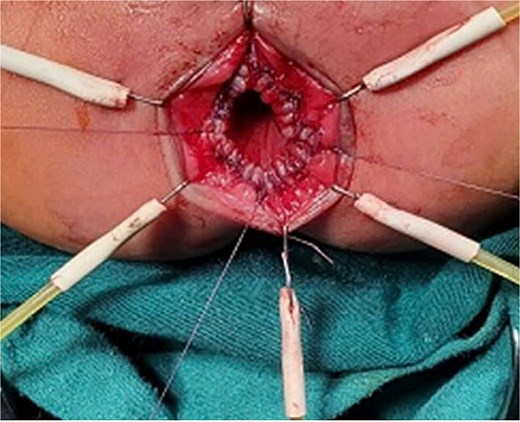

Exposing the anus with lone star retractor

The anus is exposed using a Lone Star retractor. The mucosa of the rectum is circumferentially incised 0.5–1 cm above the dentate line with a sharp electrosurgical knife and is then grasped and retracted downward using Mosquito forceps. Subsequently, the entire rectal wall layers are excised. The colon is pulled through the anus. The lymph node-negative and dilated colon segments are resected at the location of the normal bowel as determined by the frozen section biopsy.

Endoscopic re-evaluation

A re-evaluation via endoscopy is performed to exclude any tension or twisting in the mesentery. The ganglion colon is then anastomosed to the anus (Fig. 3).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0. The relationship between categorical variables will be assessed using chi-square tests, and continuous variables will be analyzed using t-tests or Wilcoxon tests with a significance level of P < 0.05. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals will be calculated based on frequency tables between categorical and outcome variables.

Results

From December 2022 to June 2024, 19 pediatric patients with classic Hirschsprung's disease underwent laparoscopic pull-through surgery combined with the Swenson-like technique. Males accounted for 78.9%, nearly four times the number of females. All patients were born full-term and had no family history of Hirschsprung's disease. The main reasons for hospitalization were constipation, abdominal distension, and diarrhea. Abdominal distension was the most prominent manifestation, observed in nine cases, accounting for 47.4%. Nine patients presented with constipation, also 47.4%, while five cases predominantly presented with diarrhea, the lowest rate at 26.3%.

In the study population, the majority of pediatric patients exhibited delayed meconium passage beyond 24 h of age, with 17 cases, accounting for 89.5%. Small and large bowel inflammation, a serious complication of Hirschsprung's disease, was observed in only five cases preoperatively, representing 26.3%. Notably, only one patient in this study presented with prolonged untreated constipation, which led to the formation of a fecaloma (Table 1).

| Characteristics . | Results . | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 19 | |

| Male/Female | 15/4 | |

| Full-term | 19 (100%) | |

| Median age (Min-Max) | 3.7 (0.8–58.3) months | |

| Reason for admission | Constipation | 9 (47.4%) |

| Abdomial distension | 9 (47.4%) | |

| Diarrhea | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Delayed meconium passage in history | 17 (89.5%) | |

| Symptoms | Fecaloma | 1 (5.3%) |

| Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis (HAEC) | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Biopsy | Suction | 13 (68.4%) |

| Open | 6 (31.6%) | |

| Characteristics . | Results . | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 19 | |

| Male/Female | 15/4 | |

| Full-term | 19 (100%) | |

| Median age (Min-Max) | 3.7 (0.8–58.3) months | |

| Reason for admission | Constipation | 9 (47.4%) |

| Abdomial distension | 9 (47.4%) | |

| Diarrhea | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Delayed meconium passage in history | 17 (89.5%) | |

| Symptoms | Fecaloma | 1 (5.3%) |

| Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis (HAEC) | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Biopsy | Suction | 13 (68.4%) |

| Open | 6 (31.6%) | |

| Characteristics . | Results . | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 19 | |

| Male/Female | 15/4 | |

| Full-term | 19 (100%) | |

| Median age (Min-Max) | 3.7 (0.8–58.3) months | |

| Reason for admission | Constipation | 9 (47.4%) |

| Abdomial distension | 9 (47.4%) | |

| Diarrhea | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Delayed meconium passage in history | 17 (89.5%) | |

| Symptoms | Fecaloma | 1 (5.3%) |

| Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis (HAEC) | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Biopsy | Suction | 13 (68.4%) |

| Open | 6 (31.6%) | |

| Characteristics . | Results . | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 19 | |

| Male/Female | 15/4 | |

| Full-term | 19 (100%) | |

| Median age (Min-Max) | 3.7 (0.8–58.3) months | |

| Reason for admission | Constipation | 9 (47.4%) |

| Abdomial distension | 9 (47.4%) | |

| Diarrhea | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Delayed meconium passage in history | 17 (89.5%) | |

| Symptoms | Fecaloma | 1 (5.3%) |

| Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis (HAEC) | 5 (26.3%) | |

| Biopsy | Suction | 13 (68.4%) |

| Open | 6 (31.6%) | |

All patients in this study underwent rectal biopsy for the preoperative diagnosis of Hirschsprung's disease. Of these, six patients (31.6%) underwent Swenson biopsy, while 13 patients (68.4%) had aspiration biopsy. The rectal biopsy results for all 19 patients confirmed the diagnosis of Hirschsprung's disease, with no cases requiring a second biopsy. The median age at the time of surgery was 3.7 months (range: 0.8–58.3 months), with the youngest patient being 0.8 months (24 days old) and the oldest being 58.3 months. The majority of patients (78.9%) underwent surgery at an age of ˂12 months, while only four cases (21.1%) were operated on after 12 months of age (Table 2).

| Characteristics . | Results . | |

|---|---|---|

| Time to initiate partial oral feeding (days) | 3.1 ± 0.8 | |

| Time to initiate full oral feeding (days) | 5.1 ± 1.3 | |

| Hospital stay (days) | 11.2 ± 3.7 | |

| Postoperative follow-up (months) | 18.1 ± 4.1 | |

| Complications | Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis | 4 (21.1%) |

| Perianal excoration | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Follow-up complications | Constipation | 0 |

| Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis | 4 (21.5%) | |

| Obstruction | 0 | |

| Length of resected bowel | 16.4 ± 5.7 cm | |

| Median operation time | 143.6 ± 42.5 min | |

| Characteristics . | Results . | |

|---|---|---|

| Time to initiate partial oral feeding (days) | 3.1 ± 0.8 | |

| Time to initiate full oral feeding (days) | 5.1 ± 1.3 | |

| Hospital stay (days) | 11.2 ± 3.7 | |

| Postoperative follow-up (months) | 18.1 ± 4.1 | |

| Complications | Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis | 4 (21.1%) |

| Perianal excoration | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Follow-up complications | Constipation | 0 |

| Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis | 4 (21.5%) | |

| Obstruction | 0 | |

| Length of resected bowel | 16.4 ± 5.7 cm | |

| Median operation time | 143.6 ± 42.5 min | |

| Characteristics . | Results . | |

|---|---|---|

| Time to initiate partial oral feeding (days) | 3.1 ± 0.8 | |

| Time to initiate full oral feeding (days) | 5.1 ± 1.3 | |

| Hospital stay (days) | 11.2 ± 3.7 | |

| Postoperative follow-up (months) | 18.1 ± 4.1 | |

| Complications | Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis | 4 (21.1%) |

| Perianal excoration | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Follow-up complications | Constipation | 0 |

| Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis | 4 (21.5%) | |

| Obstruction | 0 | |

| Length of resected bowel | 16.4 ± 5.7 cm | |

| Median operation time | 143.6 ± 42.5 min | |

| Characteristics . | Results . | |

|---|---|---|

| Time to initiate partial oral feeding (days) | 3.1 ± 0.8 | |

| Time to initiate full oral feeding (days) | 5.1 ± 1.3 | |

| Hospital stay (days) | 11.2 ± 3.7 | |

| Postoperative follow-up (months) | 18.1 ± 4.1 | |

| Complications | Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis | 4 (21.1%) |

| Perianal excoration | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Follow-up complications | Constipation | 0 |

| Hirschsprung-associated enterocolistis | 4 (21.5%) | |

| Obstruction | 0 | |

| Length of resected bowel | 16.4 ± 5.7 cm | |

| Median operation time | 143.6 ± 42.5 min | |

The mean duration of surgery was 143.6 ± 42.5 min, with the shortest procedure taking 125 min and the longest lasting 230 min. All patients in this study underwent frozen section biopsy during laparoscopic abdominal exploration, and the biopsy results of the resected bowel segment, which was subsequently anastomosed to the anus, showed the presence of mature ganglion cells. The mean length of the resected colon and rectum was 16.4 ± 5.7 cm, with the longest segment measuring 30 cm and the shortest measuring 10 cm. The majority of patients (52.9%) had ⁓15 cm of affected bowel resected. Blood loss during surgery was minimal, averaging ⁓10 ml, and no patient required blood transfusion.

Discussion

All patients in the study had a history of being born full-term, and none had a family history of Hirschsprung's disease. The literature also suggests that a family history may be associated with patients diagnosed with long-segment or total colonic aganglionosis of Hirschsprung's disease. However, no such familial association has been found in patients with classic Hirschsprung's disease [7, 8]. The median age of patients at the time of surgery was 3.7 months, with the youngest being 0.8 months and the oldest being 58.3 months. The majority of patients (78.9%) underwent surgery before 12 months of age [15]. The average age of patients was 4 monhts. Bich-Uyen Nguyen [9], the average age was 6.1 months. Early single-stage surgery offers several advantages, such as reducing the number of surgeries, shortening the hospital stay, and preventing excessive dilation of the colon. Additionally, the mesentery is less thick compared to older children, making dissection and ligation of mesenteric vessels less challenging. The discrepancy in the caliber between the healthy colon segment and the rectum is smaller, facilitating easier anastomosis, thus reducing the operative time and minimizing the risk of anastomotic leak. Furthermore, early surgery promptly addresses fecal retention, which helps to reduce the incidence of small and large bowel inflammation [1, 3, 10].

In this study, the main reasons for consultation were abdominal distension and constipation. There were five cases in which the patients presented with both abdominal distension and symptoms of foul-smelling green diarrhea, and were diagnosed with small and large bowel inflammation at birth. These clinical manifestations are commonly observed in the literature [1, 2]. All patients underwent rectal biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of Hirschsprung's disease. Surgery was performed by a surgical team using a standardized approach of laparoscopic pull-through with the Swenson technique. A frozen section biopsy was conducted to identify the presence of mature ganglion cells in the bowel segment to be anastomosed to the anus. This surgical method was also employed in the study by author Bich-Uyen Nguyen et al. [9], Tamer [11], Almetaher [12]. Menon [13] and Zhang [14] also believed that laparoscopic pull-through surgery can be performed safely with a low risk of complications. The conclusion drawn of Karlsen [15] is that there is no significant difference in postoperative complications between the transanal pull-through method and laparoscopic pull-through surgery.

In our study, all patients underwent frozen section biopsy during laparoscopic abdominal exploration. While awaiting the pathological results, we continued with dissection and mobilization, as well as ligation of the mesenteric vessels of the colon and rectum, with dissection performed close to the rectal wall, extending to the lower pelvic cavity. This approach allowed us to reduce both the surgical time and the duration of anal sphincter tension during the anastomosis stage. In all cases, the frozen section biopsy confirmed the presence of mature ganglion cells in the bowel segment. By laparoscopic pull-through surgery combined with frozen section biopsy, the bowel segment was successfully anastomosed to the normal anal canal, and no postoperative complications such as bowel volvulus or residual aganglionic segments were observed. The average surgical time in our study was similar to that of the laparoscopic surgery group in the study by author Hồ Trần Bần [5] but it was longer compared to the study by Tamer [11] and Almetaher [12]. Surgical time may also be influenced by factors such as the frozen section biopsy during the procedure and the number of surgeons involved in both abdominal and anal surgeries simultaneously. Therefore, optimizing the integration of abdominal and anal surgical stages, the time required for preparing the frozen section biopsy sample, and the pathology department's involvement is essential. During the surgery, blood loss was minimal, and no cases required blood transfusion during or after the procedure, similar to the findings of authors Bich-Uyen Nguyen and Hồ Trần Bần [5]. No cases of bowel perforation or major vascular injury were observed. Thanks to the clear visualization of the bowel segment being anastomosed to the anus during laparoscopic surgery, no cases of bowel volvulus were recorded intra-operation. The authors Karlsen [15], Tamer [11], Menon [13], and Almetaher [12] also did not report any complications during the surgery.

Our study had a longer hospital stay compared to the study by Almetaher [12]. Tamer [11] reported an unusually short hospital stay, with an average of 3.3 ± 0.2 days. This could be because in our study, patients were started on oral feeding later, and some required extended hospital stays to receive intravenous antibiotics for treating postoperative small and large bowel inflammation. Postoperative bowel dysfunction following Hirschsprung’s disease surgery remains an important issue. Fecal incontinence is typically assessed in children over the age of 3. In our study, only two patients were over 3 years old at the time of the study and had bowel movements 1–2 times per day, with no signs of incontinence or constipation. Almetaher [12] suggests that laparoscopic surgery allows for the dissection of the colon and rectum down to the pelvic cavity, which reduces the duration of anal sphincter dilation during the anastomosis stage. This, in turn, minimizes trauma to the anal sphincter and helps reduce the incidence of fecal incontinence and perianal dermatitis postoperatively. The Swenson-like technique for anal dissection helps avoid anastomotic stricture and reduces the incidence of postoperative constipation when compared to patients who underwent surgery using the Soave technique [16]. Our study noted that, at the time of the study, there were no complications related to anastomotic stricture or postoperative constipation. These results are similar to those reported by Bich-Uyen Nguyen [9]. Almetaher [12], Tamer [11] and Hoang Tran Viet [17] both performed dissection during the anastomosis stage using the Swenson-like technique. In contrast, the study by Hồ Trần Bần [5] utilized laparoscopic pull-through surgery combined with the Soave technique to treat classic Hirschsprung's disease, reporting a postoperative constipation rate of 7.3%, which is higher than the rate observed in our study.

Conclusion

Short-term outcomes of pediatric patients with Hirschsprung's disease in our study showed favorable outcomes and minimal complications. Laparoscopic pull-through surgery combined with the Swenson-like technique and frozen section biopsy is a safe and feasible approach for treating classic Hirschsprung's disease in children.

Limitation: This study has limitation such as the findings are based on clinical observations, which may introduce subjective bias, especially in the assessment of postoperative outcomes. Case-series reports, while valuable for exploring new techniques, do not offer the same level of evidence as randomized controlled trials, and thus, the long-term effectiveness and potential complications of the treatment remain uncertain.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional Human Research Bioethics Committee of Children’s Hospital 2 in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants and the Surgery Department of Children's Hospital 2, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, and Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.V., N.V.T.; methodology, H.T.V., N.V.T.; formal analysis, H.T.V., Hung. V.T.; investigation, N.V.T.; data curation, H.T.V., N.P.N.H.; writing—review and editing, H.T.V., N.V.T.; supervision, N.V.T and Linh TNU. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in this study article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.