-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jane Lim, Nicholas N. Nissen, Christopher McPhaul, Alagappan Annamalai, Andrew S. Klein, Vinay Sundaram, Peribiliary hepatic cysts presenting as hilar cholangiocarcinoma in a patient with end-stage liver disease, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 8, August 2016, rjw130, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw130

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Peribiliary cysts are cystic dilatations of peribiliary glands in the liver. They are present in ~50% of cirrhotic patients, but are underrecognized because they are usually asymptomatic and rarely present as obstructive jaundice. A 63-year-old male with hepatitis C cirrhosis, awaiting liver transplantation, had a new finding of intrahepatic dilatation on magnetic resonance imaging. This was initially concerning for cholangiocarcinoma, but was ultimately diagnosed as peribiliary cysts. Peribiliary cysts can imitate cholangiocarcinoma on imaging. Therefore, awareness of this condition is essential because misdiagnosis may lead to inappropriate delay or denial for liver transplantation. The ideal imaging modalities to identify peribiliary cysts are magnetic resonance cholangiography and drip infusion cholangiographic computed tomography, though hepatic dysfunction may limit the usefulness of the latter. Peribiliary cysts should be considered in cirrhotic patients with cholestasis, biliary dilatations and negative biopsy of the biliary system for malignancy.

INTRODUCTION

Peribiliary cysts are cystic dilatations of the peribiliary glands of the liver hilum and portal tracts, which lack communication with the lumen of the biliary tree [1, 2]. Autopsy studies have demonstrated their presence in 50% of cirrhotic livers [3]. Peribiliary cysts are often under diagnosed, however, as they are usually asymptomatic and the reported prevalence based on imaging diagnosis is only 9% in among patients with cirrhosis [4]. They are therefore often discovered incidentally, though rarely can lead to symptoms such as obstructive jaundice [5], and intrahepatic ductal dilatation on cholangiography, which may be misinterpreted as intrahepatic or hilar cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) [1, 6]. Misdiagnosis of peribiliary cysts as CCA in patients with decompensated cirrhosis may lead delay or denial in listing an otherwise suitable candidate for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). Therefore, awareness of this condition is essential for the transplant physician.

We present a case of a patient awaiting OLT, with a new finding of intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation initially thought to be secondary to CCA, but ultimately diagnosed as multiple peribiliary cysts.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old Vietnamese male with hepatitis C cirrhosis was awaiting OLT. His decompensations included hepatic encephalopathy and ascites for which he underwent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure. In May 2015, the patient was hospitalized for acute on chronic liver failure, with a rise in his Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score from 19 to 35. On physical examination, he had jaundice, abdominal distension and bilateral peripheral edema. Initial blood tests revealed an alkaline phosphatase at 599 U/L (reference <125 U/L) and total bilirubin at 13.6 (direct bilirubin 11.6). His alanine transaminase (ALT) was 122 U/L (normal 0–45 U/L) and aspartate transaminase (AST) 358 U/L (normal 0–35 U/L). The international normalized ratio (INR) was 4.2. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) was normal at 4. Baseline hepatic function tests from 2 weeks prior revealed an alkaline phosphatase of 93, total bilirubin of 6.4, direct bilirubin of 2.7, ALT of 23, AST of 85 and INR of 2.

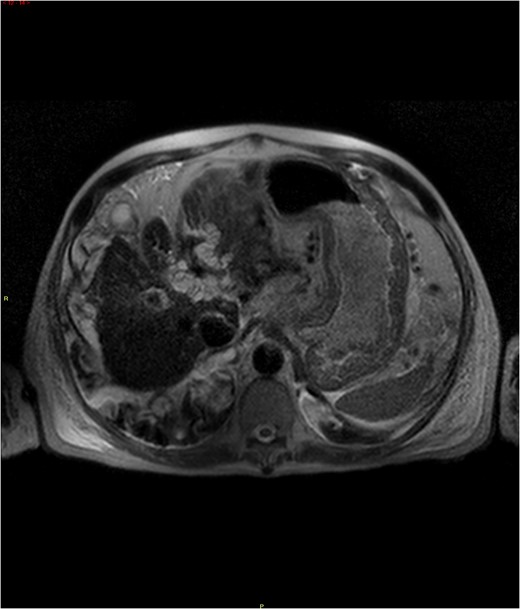

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen revealed increased T2 signal intensity within the bile ducts and significant dilation predominantly of the left biliary ductal system, with a lesser dilation of the right-sided bile ducts (Fig. 1). This was a new finding as compared to imaging from 6 months prior to hospitalization. There were no detectable hepatic or pancreatic head masses. The cholestatic pattern of liver enzyme abnormality and new biliary ductal dilatation in the absence of choledocholithiasis or a pancreatic head mass was concerning for CCA.

MRI abdomen demonstrating increased T2 signal intensities along the left bile ducts and to lesser extent the right bile ducts.

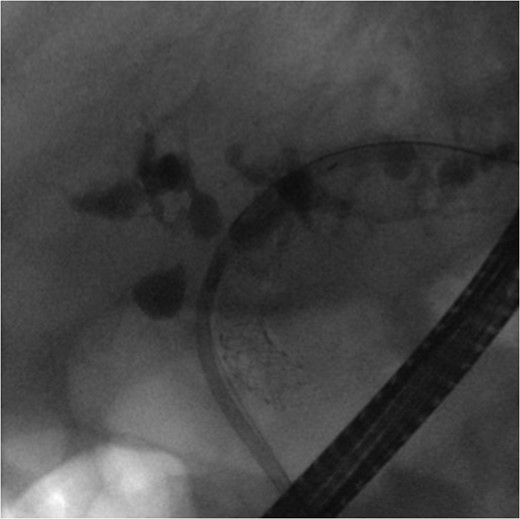

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) demonstrated a complex cystic mass at the hilum measuring 29.8 × 28.6 mm. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) revealed an irregular common hepatic duct with a stricture at the hilum and a stricture of the left intrahepatic duct, with proximal intrahepatic ductal dilation (Fig. 2). A biopsy of the biliary stricture revealed biliary mucosa without dysplasia or malignancy. There was suspicion that the liver hilum was biopsied rather than the targeted cystic mass, thus CCA could not be ruled out. The decision was made to perform a biopsy of the cystic mass at the time of OLT and to abort transplantation if there was evidence of malignancy.

ERCP demonstrating mild-to-moderate intrahepatic ductal dilatation with multifocal biliary strictures.

In June 2015, the patient underwent OLT. Both manual inspection and frozen section examinations of four lymph nodes from the portal structures and the distal margin of the common bile duct ruled out malignancy. Therefore, liver transplantation was completed.

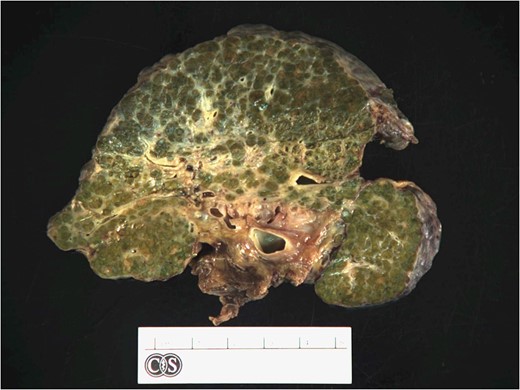

Examination of the explant revealed a 4.0 × 3.5 × 2.0 cm cystic area at the hilum, 0.2 cm from the bile duct margin. Other cysts ranged from 0.2 to 1.0 cm in diameter. The cysts appeared to run adjacent to the right and left hepatic ducts and caused focal narrowing of the bile duct lumen with proximal biliary ductal dilatation. There was no communication with the lumen of the biliary tree. These findings were diagnostic for peribiliary cysts (Figs 3 and 4).

The liver was grossly cirrhotic with an ill-defined lesion consisting of multiple variably sized cystic spaces in the hilar area that did not communicate with the bile ducts.

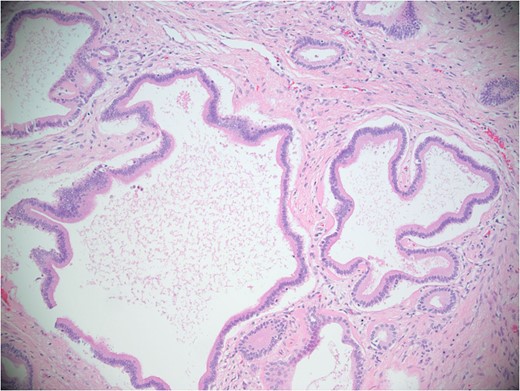

Microscopic image. Sections of the cystic spaces showed variably sized cystic structures predominately lined by simple cuboidal to columnar biliary-type epithelium.

DISCUSSION

Peribiliary cysts may present a diagnostic challenge in the patient with end-stage liver disease, due to the possibility of being mistaken for cholangiocarcinoma [3, 7]. Such a misdiagnosis can result in delay in listing for OLT or even inappropriate exclusion from transplantation, in otherwise acceptable candidates. Therefore, awareness of this condition is of critical importance to the transplant physician and surgeon.

The ideal imaging modalities to identify peribiliary cysts include magnetic resonance cholangiography/pancreatography (MRCP) and drip infusion cholangiographic computed tomography (DIC-CT). While MRI can demonstrate the presence of cysts, a diagnostic feature of peribiliary cysts is their lack of communication with the biliary tree. This can be confirmed using MRI with 2D and 3D MRCP sequences, where the cysts appear as a string of bead-like lesions along the hepatic hilum and/or bile ducts [8]. DIC-CT is another option to diagnose peribiliary cysts, though prior reports where peribiliary cysts were diagnosed by DIC-CT were in patients without liver disease [9]. DIC-CT may have a limited role in identifying peribiliary cysts in patients with decompensated cirrhosis since it requires normal hepatic function to clearly depict the bile ducts. Hepatic dysfunction and hyperbilirubinemia are known to result in insufficient delineation of the bile ducts when using DIC-CT [10]. Therefore, MRCP may be a better modality for identifying peribiliary cysts in those with end-stage liver disease.

In our patient, the diagnosis of peribiliary cysts was not made until explant examination despite performance of MRI without MRCP, EUS and ERCP. Although the patient did not undergo MRCP, the combination of MRI and ERCP could have led to a diagnosis of peribiliary cysts prior to examination of the explant. Our case, therefore, demonstrates the importance to the transplant community of being cognizant of this condition, and further suggests that a diagnosis of peribiliary cysts should be considered in patients with cirrhosis who present with intrahepatic biliary dilatations and obstructive jaundice.

In conclusion, we present a case which demonstrates that peribiliary cysts may present with imaging findings concerning for CCA. Imaging with MRCP and DIC-CT can make a definitive diagnosis, though the degree of hepatic dysfunction may limit the usefulness of DIC-CT. The diagnosis of peribiliary cystic disease should be considered in patients with end-stage liver disease who present with cholestasis and biliary ductal dilatation, along with negative biopsy of the biliary ductal system for malignancy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- magnetic resonance imaging

- computed tomography

- biopsy

- cancer

- cholangiocarcinoma

- cholestasis

- end stage liver disease

- liver cyst

- biliary tract

- cysts

- denial (psychology)

- dilatation, pathologic

- liver transplantation

- diagnostic imaging

- liver

- jaundice, obstructive

- cholangiocarcinoma, hilar

- liver dysfunction

- misdiagnosis

- cirrhosis due to hepatitis c

- infusion procedures

- magnetic resonance cholangiography