-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Laura F. Goodman, Cyrus P. Bateni, John W. Bishop, Robert J. Canter, Delayed phlegmon with gallstone fragments masquerading as soft tissue sarcoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 6, June 2016, rjw106, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw106

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Complications from lost gallstones after cholecystectomy are rare but varied from simple perihepatic abscess to empyema and expectoration of gallstones. Gallstone complications have been reported in nearly every organ system, although reports of malignant masquerade of retained gallstones are few. We present the case of an 87-year-old woman with a flank soft tissue tumor 4 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The initial clinical, radiographic and biopsy findings were consistent with soft tissue sarcoma (STS), but careful review of her case in multidisciplinary conference raised the suspicion for retained gallstones rather than STS. The patient was treated with incisional biopsy/drainage of the mass, and gallstones were retrieved. The patient recovered completely without an extensive resectional procedure, emphasizing the importance of multidisciplinary sarcoma care to optimize outcomes for potential sarcoma patients.

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the gold standard for the treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis. However, LC carries a risk of retained gallstones outside of the biliary tree [1]. A meta-analysis estimated that gallstones are lost in 5.4–19% of cases, leading to complications in 8.5% [2]. The spectrum of complications from retained gallstones includes abscess as well as erosion into organs [2]. To our knowledge, there have been no reported cases of retained gallstones with phlegmon masquerading as soft tissue sarcoma (STS).

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman presented with several weeks of right flank pain and tenderness. Past medical history included atrial fibrillation, COPD and stage III chronic kidney disease, but her overall functional status was good. Her surgical history was notable for partial colectomy for colon cancer treated by surgery alone and LC for acute cholecystitis 4 years prior to presentation. Her cholecystectomy was reported as unremarkable.

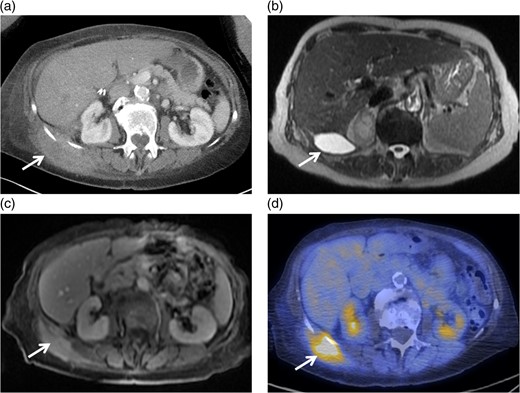

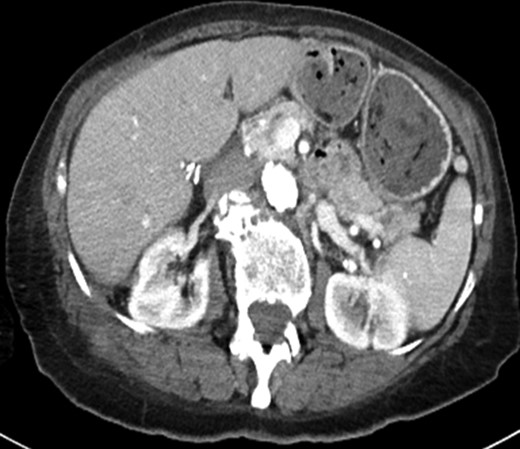

Clinical evaluation of her flank soft tissue tumor demonstrated a tender, non-erythematous, non-fluctuant 7 × 5 cm mass. Biochemical testing, including white blood cell count, was within normal limits. Computed tomography (Fig. 1a) demonstrated a 9.0 × 3.6 cm soft tissue mass and a 6.2 × 3.2 cm fluid collection abutting the right hepatic lobe and right kidney and extending into the abdominal wall. The CT findings were non specific, but the presence of a solid component with enhancing nodularity was suspicious for a neoplasm.

(a) Axial image of the CT of the abdomen with IV contrast, demonstrating a complex partially cystic, partially solid enhancing mass abutting the right hepatic lobe and right kidney and extending into the abdominal wall. (b) Axial T2-weighted sequence of the abdomen (axial T2 Single Shot Fast Spin Echo) showing the cystic component of the mass involving the right retroperitoneal space. (c) Axial T1-weighted fat saturation post-contrast sequence of the abdomen (axial T1 Liver Acquisition with Volume Acquisition after the intravenous administration of gadolinium) demonstrating enhancement of the solid component of the mass extending to the right flank musculature. (d) PET/CT showing increased FDG activity at the solid component identified on CT and MRI within the right flank musculature.

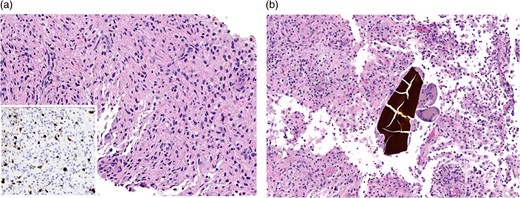

MRI confirmed the presence of a complex, partially cystic mass (Fig. 1b). The solid enhancing component extended into the right flank musculature as well as 11th and 12th ribs (Fig. 1c). Image-guided core biopsy revealed atypical spindle cells (Fig. 2a). The pathologic impression was spindle cell neoplasm, favor STS. Immunohistochemical staining revealed high Ki-67 (25%) and positive vimentin.

(a) Needle core biopsy (H&E) showing low-grade spindle cell lesion including variably increased labeling rate by Ki-67 immunohistochemistry (inset). (b) Subsequent incisional biopsy of the mass (H&E) shows a histiocytic and multinucleated giant cell response to bile concretions.

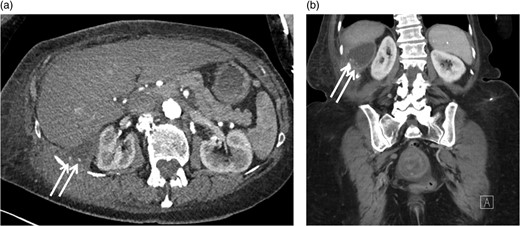

Positron emission tomography-computerized tomography revealed hypermetabolism (Fig. 1d) with maximum Standard Uptake Value of 13.4 g/ml. No overt metastatic spread was identified. The patient was referred for STS multi-disciplinary evaluation including discussion at Sarcoma Tumor Board. Careful review by a musculoskeletal radiologist highlighted the presence of cholecystectomy clips, fascial plane violation and round foci of calcium density (Fig. 3a and b). This raised suspicion for possible retained gallstones, especially since the violation of fascial planes was atypical for STS.

Axial (a) and coronal (b) CT images with IV contrast demonstrating round foci of calcium within the cystic component of the mass involving the right retroperitoneal space.

The patient was advised to undergo incisional biopsy for definitive diagnosis. Contact of the lesion with the ribs was confirmed as was communication with the retroperitoneal space. The interior of the mass was consistent with phlegmon containing necrotic tissue, and purulent fluid was obtained for microbiology.

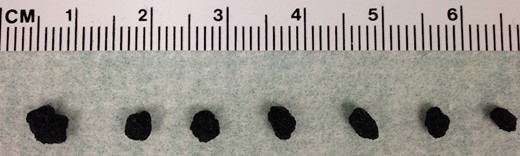

Final pathology demonstrated CD-68 positive histiocytic accumulation with bile and gallstones (Fig. 2b). The patient completed 6 weeks of postoperative antibiotics to treat culture-positive E. coli. Gallstones (Fig. 4) and fluid drained for several weeks postoperatively and then resolved. Three months after operation, a CT scan demonstrated resolution of all abnormalities (Fig. 5).

Photomicrograph demonstrating gallstones retrieved from the patient's mass at the time of incisional biopsy and for several weeks following the procedure.

Axial CT image obtained 3 months after the patient's operation showing resolution of the solid and cystic mass.

Discussion

This gallstone phlegmon masquerading as STS illustrates the importance of stepwise evaluation of soft tissue masses in a multidisciplinary sarcoma treatment center. Although the mainstay of treatment for STS is wide en bloc excision, often with radiotherapy, multimodality therapy including wide resection carries substantial morbidity and can have severe functional consequences. Therefore, a key principle of STS multidisciplinary care is to avoid under-treatment for potentially aggressive malignancies while also avoiding overtreatment for low risk or benign neoplasms [3].

Although there were several factors in this case, including the imaging studies and core biopsy results, that raised concern for STS, the correct diagnosis and management plan were rendered through careful review by a multidisciplinary sarcoma team, including surgical oncology, musculoskeletal radiology and pathology.

During multidisciplinary review, a key point of discussion was the manner in which our patient's mass violated fascial planes. This could indicate a deep STS invading through fascial planes toward the flank, but such invasion from a retroperitoneal tumor to superficial tissues is uncommon [4]. In addition, the presence of calcific masses on radiological review was also atypical for STS and raised concerns for possible retained stones, despite no indication of spillage in the operative report from LC performed several years previously.

Gallstone complications can mimic malignancy on cross-sectional imaging, as noted in a case report of a chronic peritoneal inflammatory mass due to gallstones [5]. However, a PubMed search for ‘sarcoma’ and ‘gallstone’ or ‘cholecystectomy’ revealed no English-language publications, and reports of malignant masquerade of retained gallstones are exceedingly rare. For example, one 2004 review encompassing 18 280 LCs found that 18.3% of gallbladders were perforated, 7.3% spilled gallstones and 2.4% of cases ended with un-retrieved gallstones [6]. With follow-up to 92 months, 1.7 per 1000 completed LC cases developed gallstone-related complications, but no cases of malignant masquerade were noted [6, 7].

Another concerning feature of this case was the finding of atypical spindle cells and high Ki-67 staining on initial core biopsy. Elevated Ki-67 nuclear proliferation antigen immunoreactivity has been shown in several STS studies to predict worse disease-specific mortality [8]. Although spindle cell findings on pathology are non-specific, and can be found in benign lesions, including hematoma, fat necrosis and desmoid tumors, spindle cell morphology is frequently associated with STS [9]. Since core needle biopsy results can be limited by small sample size and sampling error, it is important to review possible STS cases in a multidisciplinary setting to ensure that the clinical, imaging and pathology findings are concordant, such that an appropriate treatment plan can be formulated [10]. In equivocal cases of STS, especially when possible retained gallstones are present, incisional biopsy with attention to possible phlegmon drainage is therefore the next best step for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

In summary, in cases of suspicious soft tissue masses, the importance of referral to a Sarcoma Center with careful multimodality review and discussion of clinical, imaging and pathology findings to ensure appropriate diagnosis cannot be overemphasized. It is critical to recognize unusual features of possible sarcoma cases so that possible sarcoma masquerades can be accurately diagnosed and managed. This will spare patients unnecessary treatment and morbidity such as radical extirpative surgery and radiotherapy when there is no evidence of malignancy.

Authors’ Contributions

Laura Goodman – conception and design, literature review, writing the manuscript

Cyrus Bateni– analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the article

John Bishop – analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the article

Robert Canter – conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgements

Support for this project was provided by the UC Davis Department of Surgery.