-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Chih-Ta Huang, Szu-Kai Hsu, I-Chang Su, Regression of moyamoya-associated weak spots on the distal anterior choroidal artery following surgical revascularization, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 2, February 2016, rjw005, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw005

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 20-year-old female with moyamoya disease presented with acute intraventricular hemorrhage. Cerebral angiography demonstrated that the anterior choroidal artery (AChA) was responsible for the bleeding, but the precise point of rupture was unpredictable, because multiple angiographic weak spots were found on the artery. As direct targeting of the rupture point was unfeasible, we performed encephalo-duro-arterio-synangiosis to decrease the hemodynamic overload on the AChA. This revascularization procedure alone successfully induced the regression of all weak points. In this report, we demonstrated that, when direct targeting of weak points was not feasible, a revascularization procedure was an acceptable alternative.

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial bleeding in hemorrhagic-type moyamoya disease can arise either from the fragile moyamoya vessels or from peripheral artery pseudoaneurysms located within deep collaterals [1]. When the weak spots are located at tributaries of the choroidal arteries, they are regarded as major sources of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) [2].

The ideal therapeutic strategy for hemorrhagic-type moyamoya disease is to obliterate the bleeding source before conducting a revascularization procedure in order to prevent early re-rupture [3]. However, owing to multiple factors, direct surgical or endovascular obliteration of the bleeding source is not always feasible [3]. Surgical revascularization alone is considered effective in preventing re-rupture from moyamoya collaterals, but its role as the primary treatment for ruptured weak points arising from choroidal arteries is less clear [4].

In this report, we presented a hemorrhagic-type moyamoya patient who harbored multiple weak spots in a single AChA, the artery responsible for the hemorrhage. We described our rationale when the precise point of rupture was not able to be identified, and demonstrated the efficacy of surgical revascularization to address such a clinical scenario.

CASE REPORT

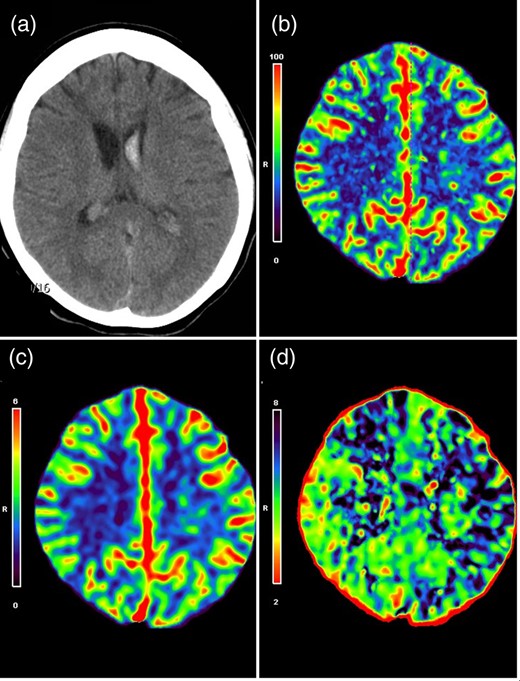

A 20-year-old female patient was admitted with a sudden onset of severe headache. Neurological examination revealed no neurological deficits, but brain computed tomography (CT) revealed an IVH mainly on the left side (Fig. 1a). This finding indicated that the bleeding point was more likely located on the choroidal arteries. Perfusion CT further demonstrated a relative hypoperfusion status in the left hemisphere, as evidenced by an increased mean transit time (MTT) in the left fronto-parietal region (Fig. 1b–d). An external ventricular drain was placed on the right side to decompress the ventricle.

(a) CT scan showed primary IVH predominantly on the left lateral ventricle. CT perfusion maps demonstrated symmetric cerebral blood flow (b) and cerebral blood volume (c), but an increased MTT on the left side (d), indicative of a relative hypoperfusion on the left hemisphere.

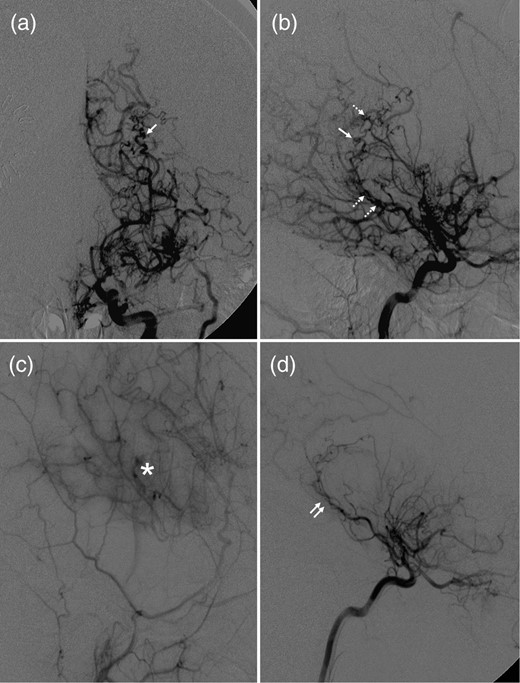

Cerebral digital subtracted angiography (DSA) revealed typical angiographic findings of moyamoya disease, which included bilateral stenosis in the terminal portion of the internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and formation of abnormal vascular networks in the region of the choroidal arteries and basal ganglia (Fig. 2a). The AChA on the left side was significantly enlarged, and provided collateral supply toward the periventricular brain parenchyma. Multiple angiographic weak points, characterized by irregular segmental dilatations and pseudoaneurysmal formation, were also noted along the intraventricular segment of the AChA (Fig. 2b).

Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) views of the right ICA angiogram demonstrated severe stenosis of the ICA termination, formation of moyamoya collateral network and multiple weak spots (dashed arrows: irregular segmental dilatations; single arrow: pseudoaneurysm) along the enlarged intraventricular segment of AChA. (c) Right external carotid angiogram demonstrated a robust collateral formation (asterisk) underlying the site of pial synangiosis. (d) Right ICA angiogram demonstrated that previous weak spots observed along the intraventricular AChA segment (double arrows) significantly regressed or disappeared.

As all these observed weak spots might be the source of the hemorrhage, the precise bleeding point could not be identified. In addition, trapping of the whole intraventricular AChA segment also carried a risk of interruption of this important collateral supply. Therefore, our treatment strategy was to perform an indirect surgical revascularization on the left hemisphere first in order to decrease collateral needs from the AChA. An additional neuroendovascular occlusion of the distal AChA could be considered later if the weak points failed to regress.

An encephalo-duro-arterio-synangiosis procedure was performed on the left hemisphere. DSA 1 year after surgery demonstrated robust collateral formation underlying the site of pial synangiosis (Fig. 2c). All weak points observed along the AChA had markedly decreased in caliber or disappeared (Fig. 2d). Therefore, additional treatment was not necessary, and the patient remained symptom-free for 4 years.

The patient has consented to the submission of the case report for submission to the journal. This case report has been approved by our local Institutional Review Board (CGH-P104079).

DISCUSSION

In adult moyamoya disease, collaterals are prone to arise more often from the choroidal arteries [2]. Hemodynamic overload of choroidal arteries makes these vessels enlarged and more fragile, and the resulting development of ‘weak spots’, which arise more often at intraventricular rather than cisternal segments, explains anatomically why these patients present primarily with IVH [5]. Hence, as in our case, neurosurgeons should look for the possible presence of rupture points on the intraventricular segments of the choroidal arteries when moyamoya patients present with IVH.

Before conducting a revascularization procedure, identification and obliteration of the bleeding source should be considered first in order to prevent re-rupture [3]. Two treatment strategies have been advocated. Open craniotomy is the traditional treatment of choice, because both bleeding point obliteration and a revascularization procedure can be performed in the same session [3]. However, owing to the deep location of the affected collateral vessels, open craniotomy often poses a greater risk of parenchymal damage [3]. Neuroendovascular approach was an alternative, which involves either bleeding point obliteration with parent vessel preservation or parent vessel occlusion [5]. In our case, however, direct rupture point targeting with AChA preservation was not feasible, because the precise source of rupture was indistinguishable. Direct AChA trapping was also too risky, because it would interrupt this important collateral supply. In other words, direct obliteration of the bleeding source in our case was not a viable option.

Another treatment option in this clinical scenario was to perform surgical revascularization alone, which theoretically would allow gradual reduction of the hemodynamic stress on deep collaterals and regression of its associated weak points within 6–12 months postoperatively [6]. However, Otawara et al. [7] reported one case in which the pseudoaneurysm did not regress, but instead ruptured 10 years after the revascularization surgery. This report reminded us that revascularization alone is not always effective in dealing with weak spots on deep collateral vessels. A follow-up DSA is mandatory in order to determine both the robustness of the collateral network established by the bypass graft and the fate of the observed weak points [7]. In our case, when synangiosis collaterals form well but weak spots fail to regress within 6–12 months, neuroendovascular trapping of the intraventricular AChA segment could be considered as a rescue procedure, given that the AChA is no longer acting as an important collateral source [7].

In conclusion, the presence of multiple weak spots without a distinguishable source of rupture poses a specific challenge in the treatment of hemorrhagic-type moyamoya disease. We demonstrated that, without direct rupture point obliteration, a successful cerebral revascularization procedure had a chance to promote gradual regression of the weak spots. However, follow-up DSA was mandatory in order to determine both the robustness of the collateral network underlying the revascularization site and the fate of the observed weak points.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.