-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Beom Jun Lee, Prashant Kumar, Rene Van den Bosch, Jejunal diverticula: a rare cause of life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 1, January 2015, rju150, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju150

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Jejunal diverticula are rare and the condition remains mostly asymptomatic. However, they can present with vague chronic abdominal symptoms and, in some cases, acute life-threatening complications, such as gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, bowel obstruction and perforation. We present a case of an adult male who presented with life-threatening GI bleeding secondary to jejunal diverticular disease. Whilst there are undoubtedly more common causes of GI bleeding, this case demonstrates that jejunal diverticular disease should remain on the differential diagnosis and investigations to confirm the diagnosis should be considered. However, despite investigations, the diagnosis may remain elusive and in patients with on-going bleeding, laparotomy and surgical resection is currently the treatment of choice.

INTRODUCTION

Jejunal diverticular disease is a rare clinical entity with an incidence of between 0.06 and 1.5% [1]. The true incidence however may be higher as the majority of jejunal diverticula are asymptomatic, and thereby remain undiagnosed.

In symptomatic cases, non-specific epigastric pain and bloating are the most common complaints [2, 3]. However, life-threatening complications such as gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, bowel perforation and obstruction have been reported in up to 18% of cases [4]. It is therefore vital that the diagnosis of the condition can be made promptly to ensure optimal and timely management for the patient.

We present a case of a 78-year-old male with massive GI bleeding secondary to jejunal diverticular disease who was surgically managed with good post-operative outcome.

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old male with a history of ischaemic heart disease, stage IV chronic kidney disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, presented to the emergency department after a sudden collapse at home. His medications included aspirin and clopidogrel.

Whilst in the department, he experienced a further syncopal event with two episodes of large-volume melaena. He was pale, clammy and haemodynamically unstable with a systolic blood pressure of 75 mmHg. His blood results showed a haemoglobin (Hb) of 66 g/l and a urea of 32.7 mmol/l. There were no reports of melaena or haematemesis prior to admission. He was initially resuscitated with intravenous fluids, red blood cells (RBCs), platelets, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and cryoprecipitate.

The patient proceeded to urgent upper GI endoscopy (OGD) but the procedure failed to identify any evidence of recent or active bleeding. Colonoscopy showed large amounts of altered blood in the colon as well as the presence of sigmoid diverticula but without evidence of active bleeding. Segmental CT-angiogram was contraindicated given patient's poor renal function.

Despite vasopressor support and a proton-pump-inhibitor infusion, with on-going melaena, the patient's Hb and blood pressure remained low, requiring 19 units of RBCs in the first 48 h of admission. Over the subsequent 36 h, the patient's condition stabilized with an Hb consistently over 90 g/l. However, on Day 4 of admission, he produced five further episodes of melaena, and became acutely tachycardic and hypotensive. His repeat Hb was 78 g/l. A repeat OGD revealed no evidence of gastric or duodenal bleeding.

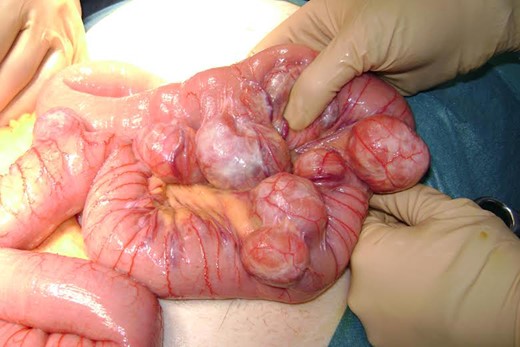

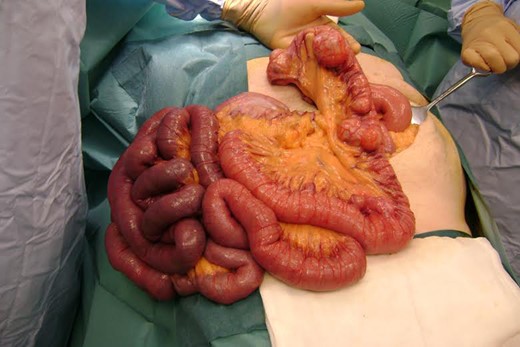

The decision was then made to proceed to exploratory laparotomy with a pre-operative plan of performing a subtotal colectomy. The presumptive diagnosis was that the bleeding was likely secondary to his known colonic diverticulosis. Intra-operatively however, we found multiple diverticula clustered along the proximal and mid jejunum at the mesenteric edge. Partially digested blood was seen in the portion of small bowel distal to these diverticula. We performed a small bowel resection of ∼80 cm length of diseased jejunum and an end-to-end anastomosis (Figs 1 and 2). Histology confirmed numerous true diverticula, with no evidence of malignancy. In total, since admission, the patient received 23 units of RBCs, 16 units of FFP, 4 units of platelets and 3 units of cryoprecipitate.

Intra-operative photography demonstrating multiple jejunal diverticula. Note that the diverticula arise at the mesenteric border and are clustered around proximal jejunum.

Intra-operative photography demonstrating jejunal diveritcula proximally and presence of altered blood in the small bowel distal to these diverticula.

Post-operatively, the patient made a slow but steady recovery. There were no further drops in Hb or episodes of GI bleeding. The patient was discharged on Day 7 post-operation and followed-up in outpatients clinic 2 weeks later. There were no further reports of bleeding and he was discharged from surgical follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Jejunal diverticular disease is an uncommon condition that is usually asymptomatic but may rarely present with life-threatening complications including massive GI bleeding [2, 3]. Other complications such as chronic malabsorption, volvulus, diverticulitis with or without perforation or abscess occur in 10–30% of patients [1, 5]. The majority of patients who present with GI bleeding do not display previous GI symptoms and are reported to develop an acute onset haemorrhage per rectum [6].

Jejunal diverticulosis is often difficult to locate endoscopically and diagnosing jejunal diverticular bleeding remains problematic, with current imaging techniques continuing to be unreliable [7]. Whilst jejunal diverticulosis can be identified by abdominal CT and barium follow-through studies [8], enteroclysis remains the investigation of choice [3]. Although some reports demonstrate success with capsule endoscopy and double balloon endoscopy [9, 10] such investigations are of limited use in emergency settings. In cases of jejunal diverticular bleeding, selective mesenteric angiography or CT angiogram can be used to localize active bleeding [6] but may be contraindicated in patients' with severe kidney impairment as with our patient.

Urgent laparotomy is indicated in the presence of acute complications of jejunal diverticula including diverticulitis, massive bleeding or bowel perforation both as a diagnostic and therapeutic measure [3, 6, 7]. Several successful cases with complete small bowel resection with primary entero-entero anastomosis have been reported [6].

Due to low incidence, low clinical index of suspicion and unreliable diagnostic imaging in emergency situations, diagnosis of jejunal diverticular disease is challenging and therefore often delayed several days after initial presentation. This has major implications with regard to prompt and timely management, and can lead to significantly increased morbidity and mortality. Whilst there are undoubtedly more common causes of GI bleeding, this case demonstrates that jejunal diverticular disease should remain on the differential diagnosis and investigations to confirm the diagnosis should be considered. However, despite investigations, the diagnosis may remain elusive and in patients with on-going bleeding, laparotomy and surgical resection is currently the treatment of choice [3, 6, 7].