-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Robert J. Grimer, Stephen C. Crockett, Extracorporeally irradiated clavicle as an autograft in tumour surgery, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 1, January 2015, rju151, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju151

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We report the case of a 45-year-old woman who presented with a lump in the mid-third of the left clavicle, which had recently increased in size to 10 cm in diameter. Plain X-ray, computed tomography and bone scans suggested that the lump was a parosteal osteosarcoma. Due to the expected 30% functional loss from claviculectomy [Wood in The results of total claviculectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;207:186–90.], the patient opted for excision of the tumour plus the adjacent clavicle, irradiation and reimplantation of the bone with internal fixation. On 2-year follow-up, there was no evidence of recurrence or complications, with a good range of movement of the joint. On 4-year follow-up, the patient was found to have discomfort, and X-rays showed that the clavicle had fractured, which was managed symptomatically.

INTRODUCTION

Malignancies of the clavicle are rare, making up just 0.45–1.01% of all bone tumours [1, 2]. Surgical intervention is the gold standard of treatment. Total claviculectomy is a rare, poorly described surgical technique [3], and to our knowledge there have been no large-scale trials on the outcome of those who have undergone this procedure. Radical ablative surgery is avoided when possible, in favour of limb salvage procedures, which involve resection of the tumour and reconstruction using a prosthesis, an allograft, a bridging technique [4] or a vascularized autograft [5]. All of these techniques come with theoretical drawbacks, which can be overcome via en bloc resection of the tumour and extracorporeal irradiation, followed by reimplantation of the irradiated bone [4], providing a perfect fitting, non-allergenic structure devoid of tumour [6]. This method means that the joint remains mobile, does not become loose or break like some massive prostheses, and the problems of bone banks and rejection of allografts can be avoided [7].

In this report, we present a case where an extracorporeally irradiated clavicle was used as an autograft to treat a suspected clavicular malignancy.

CASE REPORT

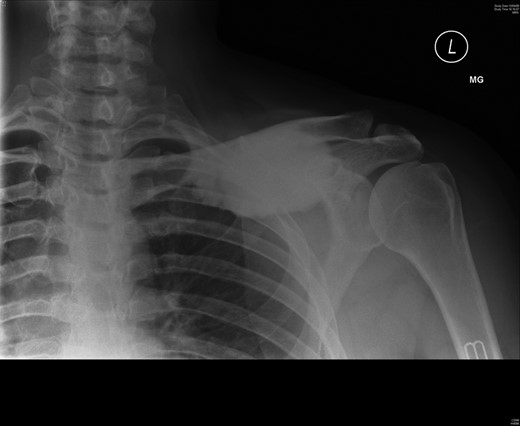

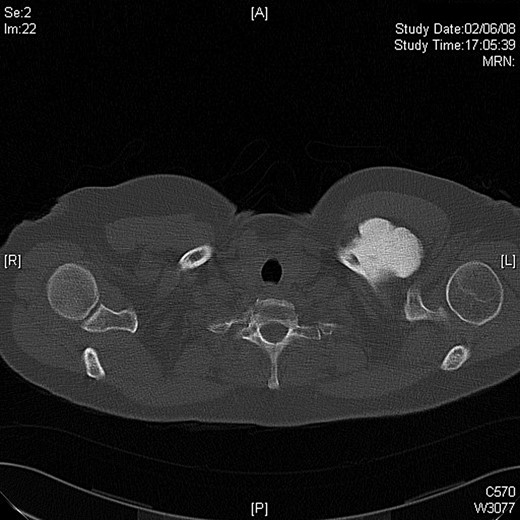

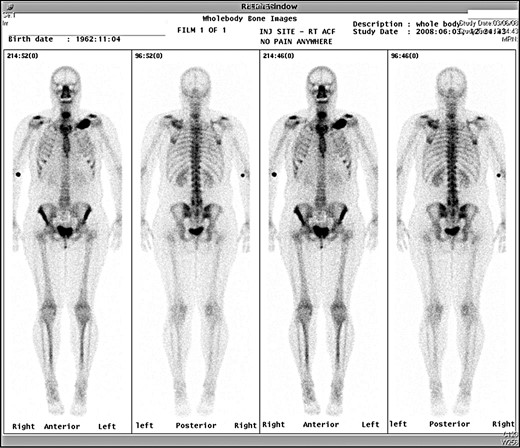

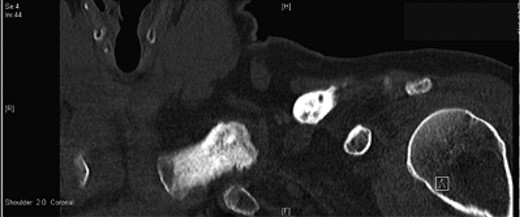

A 45-year-old woman presented with a 20-year history of a lump in the mid-third of the left clavicle, which had recently increased in size to 10 cm in diameter. Plain X-ray, computed tomography (CT) chest and clavicle, and bone scans were used to image the lesion (Figs 1–3). Radiology reported the lesion as a parosteal osteosarcoma, based on the CT appearance of tumour growing into the medulla of the mid-third of the clavicle; not usually a feature of an osteochondroma or an osteoma. Biopsies showed dense sclerotic bone, with no obvious malignant features. To confirm diagnosis complete excision of the tumour was needed, with a partial excision and scraping the lump off the surface deemed unsafe. The patient was informed that, following a total claviculectomy, a 30% functional loss (29.5% [8]) in her left shoulder power would be expected. Her active lifestyle meant this result was unacceptable, so she opted instead for excision of the tumour plus the adjacent clavicle, irradiation and reimplantation of the bone with internal fixation, despite this being relatively experimental. If successful, she would have virtually normal function. Although possible risks included infection or development of non-union, which would require further surgery or possible complete claviculectomy, it was deemed oncologically safe with a low risk of complications.

Preoperative CT scan, axial view showing the extent of the tumour.

The surgery was carried out through an incision over the clavicle and the tumour was carefully dissected leaving a layer of normal tissue over the mass. The clavicle was then removed by resection through the sterno-clavicular and acromio-clavicular joints and careful division of the subclavius muscle, preserving the underlying neurovascular structures. The main mass of the tumour was then stripped from the clavicle, leaving the residual bone and the attached ligaments. The bone was then soaked in a solution of vancomycin 1 g dissolved in 200 ml of saline, wrapped in swabs and then two sterile bowel bags. Irradiation of the bone with 90 Gy was then carried out at the local radiotherapy unit. After 1.5 hours, the bone was removed from the sterile bowel bags and reimplanted. The conoid and trapezoid ligaments were repaired as were the ligaments and capsule at either end of the bone, with a plate applied to the bone to strengthen it. The wound was closed and the patient advised to use a sling for 6 weeks. Post-op histology confirmed that the lump was a benign giant osteoma.

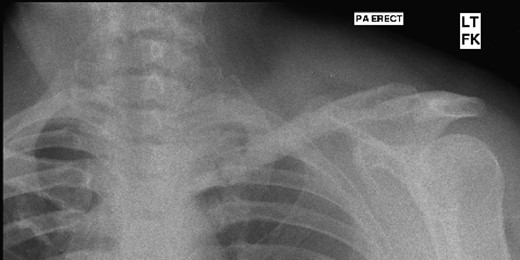

The patient had 3 monthly follow-up and at 2 years, there was no evidence of local recurrence or complications. She had a full and pain-free range of motion of the shoulder and was completely asymptomatic (Fig. 4).

Four years following the procedure, after discomfort in her shoulder, X-rays revealed that the plate had broken and there was a fracture of the clavicle. This plate was subsequently removed and an underlying non-union was found, but no evidence of recurrence of the tumour. She has been managed symptomatically since and has a full range of shoulder movements but some discomfort when doing heavy lifting, which she therefore avoids (Figs 5 and 6).

DISCUSSION

Surgical treatment of clavicular tumours can be extremely difficult without total resection of the clavicle. For our patient, the potential reduction in normal function that comes with total claviculectomy was unacceptable. Reconstruction of the clavicle can be achieved using a variety of techniques [4], with resection of the tumour and extracorporeal irradiation followed by reimplantation of the irradiated bone, being chosen in this case. It is essential that the functional outcome of the method chosen at least equals that of the more radical procedure, total or partial claviculectomy.

Reconstructive surgery is useful cosmetically, as well as functionally, although there are case studies which argue the difference is minimal compared with claviculectomy [3, 8, 9]. Extracorporeal irradiation and reimplantation of the patient's own clavicle is a useful method of limb salvage. After irradiation, the clavicle is free of tumour, and can be used as a scaffold for reattachment of muscles and ligaments [6]. There are inherent risks with this procedure, as it prolongs operative time, with a study in 20 patients showing a 15% risk of infection, a 25% risk of non-union and a 5% risk of fracture [10].

Previous studies on the functional outcome of patients who undergo total claviculectomy have been contrasting, with some finding the function to be 70.5% of normal [8]. In our patient, she was completely asymptomatic at 2-year follow-up, with a full range of motion of the shoulder and no evidence of local recurrence or complications. However, she then developed a fracture 2 years following this, which meant the plate needed to be removed. Despite this, the patient still has a good range of movement and any pain experienced has not been sufficient to warrant any further intervention.

In summary, extracorporeal irradiation followed by reimplantation of the clavicle is a useful alternative to total claviculectomy for certain low grade tumours of the clavicle, as it provides functional, cosmetic and oncological outcomes that are equal to, if not superior those of total claviculectomy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the patient on whom this case report is based for their co-operation.