-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rikesh K. Patel, Adele E. Sayers, James Gunn, Management of a complex recurrent perineal hernia, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 8, August 2013, rjt056, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjt056

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Symptomatic perineal hernias following abdomino-perineal excision of rectum have been reported to occur uncommonly. We present the case of a 79-year-old gentleman who developed a perineal hernia after laparoscopic-assisted extralevator abdomino-perineal excision (ELAPE) of the rectum. Despite initial myocutaneous flap repair, there was further symptomatic recurrence. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated non-compromised bowel extending beneath the gracilis flap with extension into the adductor compartment of the left thigh. Given the recurrent nature, a rectus flap repair was performed and after 15 months, he remains hernia free. There is currently no consensus as to the optimal operative technique in the prevention and management of these hernias; however, primary reconstruction at the time of ELAPE may be preferable. Symptomatic perineal hernias can be severely debilitating and require operative repair. We suggest that surgical options should be discussed and carried out with the input of a Plastic surgeon.

INTRODUCTION

Perineal hernias following abdomino-perineal excision of rectum (APER), requiring repair, have been reported to occur in <1% [1, 2] of people. Patients may exhibit some perineal bulging following an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, but are rarely symptomatic and, therefore, do not require operative intervention. The literature to date has reported that perineal hernias occur primarily following APER; however, there is very little data with regard to incidence and the management of perineal hernias.

CASE REPORT

A 79-year-old gentleman who initially underwent a laparoscopic assisted extralevator abdomino-perineal excision (ELAPE) of the rectum for extensive circumferential low rectal cancer after neo-adjuvant long course chemoradiotherapy developed a symptomatic perineal hernia. Initial closure of the perineal wound was performed using a double layer of interrupted mattress sutures with a 2/0 absorbable braided suture. The patient's only co-morbidity was intermittent asthma, for which he was prescribed a Salbutamol inhaler.

Given the nature of the disease, it was felt that he would benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Subsequent radiological surveillance did not show any evidence of recurrence and CEA levels remained low. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) carried out at 19 months demonstrated that the small bowel had herniated through the levator sling and the patient had started to experience severe discomfort in the perineal region.

Repair of the defect was carried out in conjunction with the Plastic surgery team, using a pedicled gracilis flap. Again, despite an uneventful recovery, 5 months later the patient experienced lower abdominal pain and nausea and noted a distinct swelling of his left upper thigh.

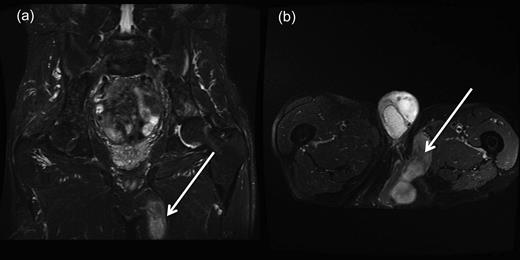

A repeat MRI confirmed a further recurrence of the perineal hernia in the form of uncompromised bowel, which extended beneath the gracilis flap, which then continued into the adductor compartment of the left thigh (Fig. 1a and b).

(a and b) Coronal and transverse magnetic resonance imaging scans demonstrating perineal hernia extending into the left thigh. (Demonstrated by white arrows.)

Given the recurrent nature of the hernia, a rectus flap repair was performed and after 15 months he remains hernia free.

DISCUSSION

Although the majority of patients after APER will demonstrate an element of perineal herniation, they do not exhibit any symptoms and, therefore, do not require operative repair. The overall incidence of perineal herniation is thus likely to be higher than reported. Commonly reported symptoms secondary to perineal hernias include perineal discomfort, a dragging sensation, skin breakdown, urinary dysfunction, bowel obstruction and evisceration of pelvic contents [1–4].

Given the paucity of available literature, it is difficult to identify definitive predisposing factors; however, reported factors include smoking, chemoradiotherapy, sacrectomy/coccygectomy, excessive length of small bowel, lack of peritoneal closure and excision of the levators [1, 2, 4].

With conventional APER, involvement of circumferential resection margins (CRM) has been identified to occur most commonly at the floor of the pelvis [5]. The aim of ELAPE is to reduce this CRM positivity, along with rates of intra-operative perforation. Tissue morphometry of ELAPE specimens showed that this reduction in CRM positivity occurs as a result of removing more tissue from around the tumour than standard APER, and thus improving rates of local recurrence and overall survival [6]. Despite these superior oncological outcomes, ELAPE has also been associated with an increase in perineal wound complications, which may be attributed to the increased size of the perineal defect [6].

There has been an increase in the uptake of laparoscopic APER in recent years, which may be attributed to an increase in the incidence of perineal hernias [7]; however, actual figures have not been reported. A possible reason is that a laparoscopic technique may result in fewer adhesions and thus less restriction of small bowel herniation [8]. Our patient had undergone both neo-adjuvant and adjuvant therapy, along with a laparoscopic ELAPE.

Foster et al. [9]'s systematic review on the outcome of primary perineal reconstruction following ELAPE demonstrated lower rates of perineal complications compared with primary closure. There has been debate surrounding reconstructive technique, but no significant differences in perineal complication rates have been demonstrated between biological mesh and myocutanous flap reconstruction [9]. Primary reconstruction using biological mesh may be preferable due to shorter operating times, absence of donor site morbidity and the option of operating independent of a Plastic surgeon. However, the tendency for biological mesh to thin with time, leading to possible recurrence and the risk of infection, may make some opt for myocutanous flap reconstruction [3]. Cost benefits have been suggested when using a biological mesh over a rectus abdominis flap due to their association with a reduced length of post-operative stay [10]. Due to the variety of flap reconstructions reported and due to relatively low numbers in each study, preference is still yet to be determined.

There is also debate as to the optimal operative approach in managing perineal hernias. The use of a transabdominal technique allows of better visualisation of the defect and allows identification of tumour recurrence, while a transperineal approach minimises the potential risks associated with entering the peritoneal cavity [3]. Laparoscopic repair has been shown to have results comparable with those of open repair, but is dependent on patient selection (body habitus, comorbidities, intraperitoneal adhesions) [3].

No consensus currently exists as to which method of repair is the best. Perineal hernia repair can be a challenging procedure, with a recurrence rate of up to 30% [4]; Foster et al. [9] demonstrated that primary reconstruction at the time of ELAPE may be preferable to potentially prevent perineal hernias. Presently, it is thought that a high-quality prospective trial is needed to help answer the many questions that arise between surgeons when discussing the management options for perineal hernias.

Symptomatic perineal hernias can be severely debilitating and require operative repair. Repair after ELAPE poses a significant challenge; hence, further research is needed to determine the best method of managing and preventing this difficult complication.

However, we advocate that management of the perineal defect at the time of initial surgery should be discussed and carried out with the input of the Plastic surgeons.