-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Amalie K Kropp Lopez, Richard A Lopez, Traumatic pediatric bear injury resulting in cerebrospinal fluid leakage, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 8, August 2024, rjae235, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae235

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage is a known sequela of open traumatic skull fractures within the pediatric traumatic brain injury population. Black bears are a known entity within the region of northeast Pennsylvania. It is plausible to have a bear–human interaction resulting in significant bodily injury. A 15-month-old male presented in May 2023 as a level 1 trauma alert for a concerning wound at the base of the skull leaking clear fluid; suspicious for CSF. As a result of this interaction, significant bodily injury can occur, such as CSF leaks and traumatic skull fractures. Living in a region within a known bear population poses a minimal risk of injury. Pediatric populations are usually at a low risk for traumatic CSF leaks. Most of the CSF leaks will resolve spontaneously, without acute surgical intervention, as was seen in our patient after a traumatic bear mauling.

Introduction

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage is a known sequela of open traumatic skull fractures within the pediatric traumatic brain injury population. Black bears are a known entity within the region of northeast Pennsylvania. It is plausible to have a bear–human interaction resulting in significant bodily injury.

Case body

A 15-month-old male presented in May 2023 as a level 1 trauma alert for a concerning wound at the base of the skull leaking clear fluid; suspicious for CSF. Per the patient’s mother, he was attacked by a bear 2 days prior. The only witness to the event was the patient’s 5-year-old brother who stated he saw the black bear carry the patient off into the woods. Following the initial encounter, the patient was seen at a different hospital where the wounds sustained during the alleged attack were sutured. He was prescribed oral Augmentin and discharged with pediatrician follow-up. No imaging was obtained at the initial encounter. The patient and mother later presented to their pediatrician who had concerns there was a potential CSF leak, prompting them to go to the emergency department.

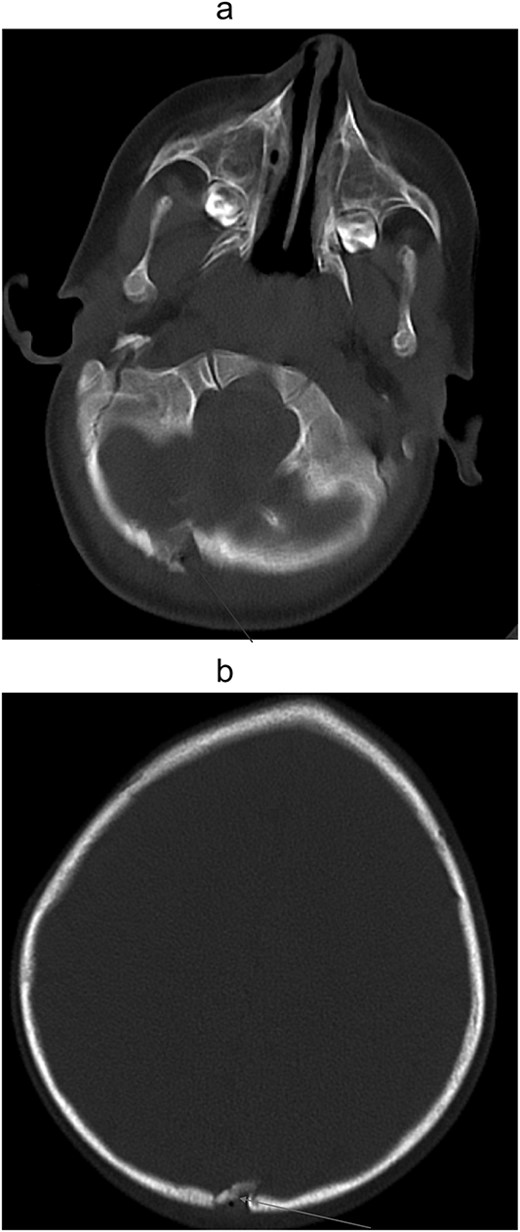

During the secondary survey of the patient, he was found to be in sinus tachycardia, with three lacerations to the scalp closed with suture and staples, and an inferior neck wound with surrounding erythema and clear drainage. Multiple wounds on his back were closed with sutures, and tender to palpation with ecchymosis (Fig. 1). Also, three wounds to his bilateral buttock. Initial labs showed lactic acidosis and leukocytosis. He was started on Vancomycin, Rocephin, and intravenous fluids. CT imaging of the head showed an acute penetrating injury at three sites, with left parietal and occipital scalp laceration and associated depressed comminuted calvarial fractures with trace pneumocephalus, along with a right lung pulmonary contusion and penetrating left buttock wound (Figs 2 and 3). He was transferred to a pediatric trauma center with an established PICU and pediatric neurosurgery for further care and treatment. It was elected to proceed with the least invasive option to oversew the leaking wound at the bedside and a lumbar puncture was obtained to evaluate for possible meningitis. The patient ultimately received tetanus prophylaxis and treatment as well as an empiric course of antibiotics directed against meningitis and was discharged to home with his mother with outpatient follow-up.

Image obtained during secondary survey of patient. Visible puncture wounds closed with suture closed during a prior encounter. Visible, presumed, CSF leaking from posterior aspect of the patient’s midline neck.

(a) Non-contrast computed tomography of head/brain, sagittal view showing Acute penetrating injury at three sites, with left parietal and occipital scalp laceration and associated depressed comminuted calvarial fractures. Trace extra-axial hemorrhage associated with the fracture of the inferior occipital calvarium and focal edema of the right cerebellar hemisphere, suggesting a small contusion and/or laceration. (b) Noncontract computed tomography of head/brain, sagittal view showing Acute penetrating injury at three sites, with left parietal and occipital scalp laceration and associated depressed comminuted calvarial fractures. Trace extra-axial hemorrhage associated with the fracture of the inferior occipital calvarium and focal edema of the right cerebellar hemisphere, suggesting a small contusion and/or laceration.

Intravenous contrast computed tomography of chest, abdomen, and pelvis showing right upper lobe pulmonary contusion/laceration. No pneumothorax or pleural effusion.

Discussion

Black bears in Pennsylvania

Ursus americanus, the black bear's scientific name, is the only resident bear of Pennsylvania, with over 20 000 residing in the commonwealth as of 2015 [1]. Because the populations of bears are likely to increase with conservation efforts, it is also reasonable to assume an increase in bear–human interactions. While fatal attacks are exceedingly rare and not documented in recent times in Pennsylvania, interactions may result in injuries. Black bears are found to have a bite force of up to 800 PSI [2]. This amount of force is more than enough to cause extensive damage to bone and surrounding structures.

Our patient lives in an area known to have a bear population and is next to a wooded area. During the chart review, there were different accounts, but they were centered around a narrative of a black bear knocking the 5-year-old brother out of the way and picking up the patient, carrying him into the woods. The grandmother and 14-year-old sister also stated they possibly saw the bear.

Management of pediatric skull fractures

Head trauma in the pediatric population is a common cause of morbidity and mortality. The skull of a pediatric patient tends to be more compliant than that of an adult, therefore injuries to skeletal structures may not present as a frank fracture. Their skulls are thinner, making them more susceptible to brain injuries [3]. Despite blunt force alone to the skull, when injuries are not grossly apparent, imaging is a useful and needed modality for workup of the potentially devastating injuries and was warranted at the time. In our patient, imaging was not completed on the initial encounter, therefore delaying the ultimate treatment for the patient.

Management of CSF leaks in trauma

Traumatic CSF leaks are found in ~10–30% of skull base fractures. More than half of these are discovered within 48 h and almost all occur within 3 months in adult trauma patients [4]. Within the pediatric population, traumatic CSF leakage occurs in 2% of all traumatic brain injuries and 12–30% in cases associated with skull base fractures [5]. Luckily for most cases, leakage of the CSF due to trauma resolves spontaneously within the week, and 70% of patients within the first few months [6].

Treatment of CSF leakage includes observation, CSF diversion, and extracranial and intracranial procedures. Our neurosurgery team gave the patient multiple different options ranging from observation to more invasive surgical intervention. Current literature shows that post-traumatic CSF leaks are uncommon and will typically resolve without any surgical intervention [7]. Our patient’s mother opted for the oversewing of the wound, which ultimately did resolve his CSF leak.

It is also important for proper antibiotic coverage of bear and animal bites. Organisms that have been most commonly isolated from the oral cavities of black bears include Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Escherichia coli, and Enterobacter spp [8]. Seeking medical attention greater than 6–12 h greatly increases the risk of an infection. Recommend antibiotics for these types of wounds require broad spectrum such as ß-lactam or third generation cephalosporins [9]. Upon our patient’s first encounter with medical care following the attack, he was prescribed Augmentin, the gold standard for these types of bites. While in our care, our patient received Rocephin during the trauma workup, which provided continued proper coverage against infection. It is also commonly recommended to receive a tetanus vaccine.

Conclusion

Living in a region within a known bear population does pose a very minimal risk of injury. Pediatric populations are usually at a low risk for traumatic CSF leaks. Most of the CSF leaks will resolve spontaneously, without acute surgical intervention, as was seen in our patient after a traumatic bear mauling.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.