-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yuki Akaguma, Hideki Tsubota, Masanori Honda, Masafumi Kudo, Hitoshi Okabayashi, Aortoprofunda and internal iliac bypass in open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm with aortoiliac occlusive disease, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjaf1020, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf1020

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

An 83-year-old man with prior coronary bypass and iliac stenting presented with bilateral claudication. Ankle–brachial indices were immeasurable. Computed tomography revealed an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm and bilateral iliac occlusion with severe calcification, while runoff depended on profunda femoris collaterals. Open repair was performed with infrarenal aortic replacement using a three-branched graft to the right internal iliac and bilateral profunda femoris arteries. Postoperatively, ankle–brachial indices improved to 0.58/0.57, imaging confirmed graft patency, and symptoms resolved. This case highlights profunda femoris and internal iliac arteries as effective outflow targets when conventional aortobifemoral bypass is not feasible.

Introduction

Aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD) frequently presents with intermittent claudication or critical limb ischemia, and aortobifemoral bypass is considered the gold standard surgical treatment for extensive lesions. However, in cases where the common femoral or iliac arteries are unsuitable as outflow vessels, alternative targets such as the profunda femoris may be required. Concomitant abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) with AIOD presents an additional challenge, as both aneurysm exclusion and durable limb revascularization must be achieved. Although aortoprofunda bypass has been reported as a reliable option, cases combining aneurysm replacement with multiple distal reconstructions involving the profunda femoris and internal iliac arteries are rare. We report a case of AAA with AIOD successfully treated by open aortic replacement and concomitant bypass to the bilateral profunda femoris and right internal iliac arteries. Patient consent for publication was obtained.

Case report

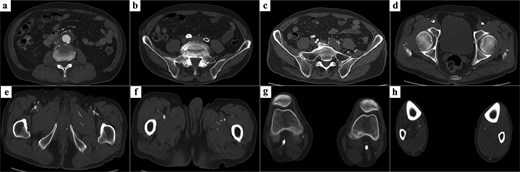

An 83-year-old man with a history of coronary artery bypass grafting, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and hypertension presented with intermittent claudication of both legs. Eleven years earlier, he had undergone stent placement in the right common and external iliac arteries for AIOD. At this presentation, ankle–brachial indices (ABI) were immeasurable bilaterally. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed an infrarenal AAA and occlusion of the right external and left common iliac arteries due to severe atherosclerosis and calcification (Fig. 1, Video 1). The bilateral superficial femoral arteries were heavily calcified, and distal runoff was dependent on profunda femoris collaterals. Therefore, surgical planning included open AAA repair with concomitant aorto–bilateral profunda femoris bypass. The right internal iliac artery had favorable quality and was also selected as an additional outflow target.

Preoperative CT findings. (a) A 40-mm infrarenal AAA. (b) Complete occlusion of the left common iliac artery. (c) A patent right internal iliac artery with favorable quality. (d) Occlusion from the right external iliac artery to the common femoral artery because of severe calcification. (e) Occlusion of the right superficial femoral artery and a patent profunda femoris artery serving as the target outflow vessel. (f) A patent left profunda femoris artery. (g) Severe calcification of both popliteal arteries. (h) Distal runoff beyond the tibial trifurcation was maintained via collateral flow from the profunda femoris artery.

Through a transperitoneal midline incision, the infrarenal abdominal aorta and bilateral iliac arteries were exposed. Bilateral groin incisions were made to isolate the profunda femoris arteries. The peritoneum anterior to both external iliac arteries was incised and extended by blunt dissection to the groins, creating graft tunnels that passed posterior to the ureters. After systemic heparinization, the infrarenal abdominal aorta and right internal and external iliac arteries were clamped without any protection, and the aneurysm sac was opened. Hemorrhage from the lumbar arteries was managed by ligating them from within the aneurysmal sac. The inferior mesenteric artery was occluded with no backflow. A three-branched Intergard graft (17 × 7 × 7 mm; Getinge, Gothenburg, Sweden) was anastomosed end-to-end to the infrarenal aorta. One branch was anastomosed end-to-end to the right internal iliac artery. The remaining branches were passed through the preformed tunnels and anastomosed end-to-side to the bilateral profunda femoris arteries. Because the left profunda femoris artery was calcified and anastomosis was technically challenging, partial endarterectomy was performed. At the other anastomotic sites, neither endarterectomy nor angioplasty was required. The right external iliac artery was oversewn with felt reinforcement, and the left common femoral artery, filled with atheroma and lacking backflow, was not reconstructed because preoperative CT revealed severe calcification of the left superficial femoral artery and the blood flow to the left leg depended mainly on the profunda femoris artery (Supplementary Fig. 1). The operative time was 318 minutes, the aortic cross-clamp time was 23 minutes, and the total blood loss was 208 mL; no blood transfusion was required. Postoperative ABI improved to 0.58 on the right and 0.57 on the left. Postoperatively, the patient received single antiplatelet therapy with aspirin. Postoperative CT demonstrated excellent graft patency, and claudication resolved completely (Fig. 2, Video 2). The postoperative course was uneventful, and no recurrence of claudication was observed during outpatient follow-up. However, the patient experienced sudden unexpected death at home 3.5 years after surgery, with the cause remaining unknown.

Postoperative three-dimensional CT demonstrating well-reconstructed aorto-profunda and internal iliac bypasses.

Discussion

Aortoprofunda femoris bypass is a recognized surgical option for AIOD when the common femoral arteries are unsuitable as distal targets. Previous studies have demonstrated comparable long-term patency and limb salvage rates to conventional aortofemoral bypasses [1]. Endovascular repair has also emerged as an alternative for extensive AIOD, with favorable long-term outcomes reported [2, 3]. However, in this case, endovascular therapy was not feasible due to poor access vessel quality, as both the right external iliac artery and the left common iliac artery were occluded, leaving no suitable route for endovascular intervention. A transperitoneal midline approach was selected because it provided wide exposure of the infrarenal aorta for proximal anastomosis and facilitated multiple distal reconstructions. A unilateral retroperitoneal approach would have limited contralateral access. Extra-anatomic bypasses have been associated with inferior long-term patency compared to anatomic aortofemoral bypass [4]. Furthermore, open surgery allowed simultaneous aneurysm repair and durable revascularization in a single-stage procedure. Concomitant iliac occlusive disease has been reported to negatively affect outcomes of open repair for AAA, with increased perioperative complications and reduced long-term survival compared with isolated aneurysm repair [5]. In this context, our case highlights the feasibility of achieving both aneurysm exclusion and limb revascularization by employing the profunda femoris and internal iliac arteries as alternative outflow vessels. Such a strategy may help optimize outcomes in this high-risk subgroup.

Although there was no significant difference in the incidence of pelvic ischemia between patients with and without internal iliac artery reconstruction, the incidence of gluteal claudication was significantly lower in the reconstructed group (9.5% vs 2.3%) [6]. Because interruption of internal iliac artery flow is known to cause deterioration of sexual function, reconstruction of the right internal iliac artery was performed in this case to minimize the risk of such complications [7].

Although an additional bypass to the infrapopliteal arteries might have further augmented limb perfusion, the procedure was not performed as symptom resolution was achieved with the present reconstruction.

Conclusions

In patients with concomitant AAA and AIOD, surgical planning can be particularly challenging when the common femoral and iliac arteries are unsuitable as distal targets. This case demonstrates that the profunda femoris and internal iliac arteries can serve as reliable outflow vessels, allowing for effective limb revascularization in combination with aneurysm repair. This strategy may represent a valuable surgical option in complex cases where conventional aortobifemoral bypass is not feasible.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Consent for publication

Written patient’s informed consent was obtained.

References

- abdominal aortic aneurysm

- aorta

- aortoiliac atherosclerosis

- leriche syndrome

- stents

- coronary artery bypass surgery

- computed tomography

- iliac artery occlusion

- profunda femoris artery

- lameness

- ankle

- iliac artery

- ilium

- tissue transplants

- diagnostic imaging

- bypass

- aorta abdominal aneurysm, infrarenal

- open repair of aortic abdominal aneurysm

- internal iliac artery

- aortic bifurcation bypass graft

- calcification