-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jurgienne Umali, Jenelle Taylor, Successful surgical resection of an incidental primary lung giant cell carcinoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 10, October 2024, rjae634, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae634

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Giant cell carcinomas of the lung (GCCL) are aggressive tumors, with most patients having metastatic disease at presentation. However, giant cell carcinomas of the lungs are rare and account for 0.1%–0.4% of primary lung malignancies. Thus, the literature on the disease is limited. This case report presents an asymptomatic young patient with an incidental lung mass on a background of childhood abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma with lung metastasis. After undergoing surgical resection, the final tumor pathology was in keeping with primary giant cell carcinoma. The purpose of this case report is to contribute to the understanding of giant cell carcinomas of the lung.

Introduction

Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma (PSC) is a rare subtype of primary lung malignancies. According to the 2021 World Health Organization classification of thoracic tumors, within this subtype are pleiomorphic carcinomas, which include giant cell carcinomas [1]. Giant cell carcinomas of the lung (GCCL) account for 0.1%–0.4% of primary lung malignancies [2]. More than 50% of GCCL cases have been reported to be located in the upper lobes of the lung, with surgical resection being the mainstay of treatment [2].

We report a case of a 36-year-old patient with a smoking history and multiple malignancies, most notably a childhood history of abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma with lung metastasis, who received a diagnosis of primary GCCL after undergoing complete surgical resection of an incidentally found lung mass.

Case report

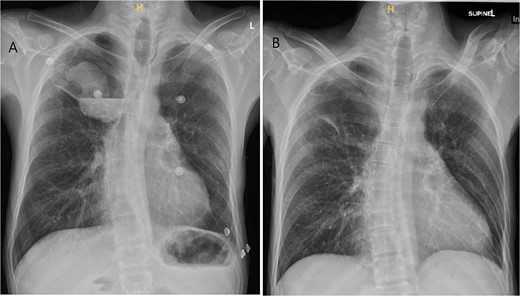

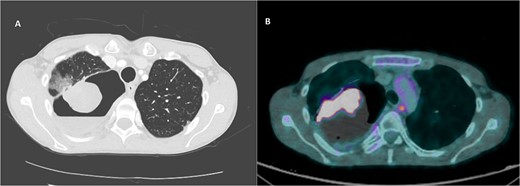

A 36-year-old male was referred to the Thoracic Surgery Service due to an incidental finding of a 5-cm soft tissue density within a known long-standing large right apical bulla on a chest X-ray (Fig. 1A). This lesion was new compared to the patient’s last chest X-ray 5 months prior (Fig. 1B). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated a 4.4 × 5.2 cm intracavitary solid-appearing mass within the wall of the longstanding bulla, along with heterogeneous fluid layering within the cavity with questionable enhancement (Fig. 2). This was reported as concerning for a primary bronchogenic malignancy (versus adherent fungus ball) with a superimposed infection. The patient had no respiratory or constitutional symptoms.

Chest X-ray imaging of incidentally found right new apical lung mass (A). This lesion was absent in the patient’s X-ray taken 5 months prior (B).

CT imaging of right intracavitary lung mass found within the wall of a longstanding bulla, along with heterogeneous fluid layering within the cavity (A). The mass was reported to be 4.4 × 5.2 cm and was concerning for primary bronchogenic malignancy. This lesion increased to 6.8 × 5.9 cm, demonstrating intense increased FDG activity and interval increase in fluid layering within the bulla within 2 months on follow-up PET imaging (B).

The patient has had previous admissions for abdominal pain related to superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Past medical history includes Type 1 Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome, Noonan syndrome, peptic ulcer disease, intermittent hypercalcemia, depression, and anxiety. The patient had an extensive surgical history, namely resection of pancreatic tumors and subtotal parathyroidectomy and thymectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism secondary to hyperplasia. Of note, the patient had abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma at the age of 2, with metastasis to the left lung at age 3, both of which required surgical resection.

The patient was a current smoker with over three-fourth pack per day for ~20 years and smoked cannabis daily. He denied alcohol consumption. The patient worked as a millwright, with the possibility of industrial occupational exposure. Family history was significant for pancreatic cancer and lung cancer.

On examination, the patient appeared thin and older than the stated age. Head and neck examination was unremarkable. A left thoracotomy incision scar and multiple abdominal laparotomy scars were visualized on the exam. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

As the patient lived in a rural community, travel to the tertiary care center with access to further diagnostic imaging services, specifically positron emission tomography (PET scan), was challenging. The patient also had social challenges that impacted his ability to attend appointments. Efforts were made to see the patient in traveling clinics and through telephone appointments to address these challenges. His PET scan was delayed because of the aforementioned issues.

A PET scan done 2 months after the original CT scan showed that the lesion had increased in size (3.3 × 6.8 × 5.9 cm compared to previous CT findings of 2.7 × 3.9 cm), and demonstrated intense increased fludeoxyglucose (FDG) activity, with several smaller foci of similar intense grade FDG avid soft tissue nodules along the posterior aspect of the inferior bulla (Fig. 2). There was also an interval increase in fluid layering within the bulla. There was no distant metastasis.

Given that the lesion was located within a large bulla of the lung, a biopsy was deemed high-risk for iatrogenic pneumothorax.

Our working diagnosis preoperatively was metastatic recurrence, given the history of abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma. Primary bronchogenic carcinoma and infectious processes were also on our differential. Given the concern for malignancy, the patient was taken to the operating room for surgical resection. On pleuroscopy, an obvious mass encasing the upper lobe of the right lung was visualized, with adhesions to the chest wall, albeit with no overt invasion. The mass was encompassing about half of the right pleural space. Unusual-appearing pleural deposits were identified; however, frozen sections showed no malignant cells. As such, the mass was then resected.

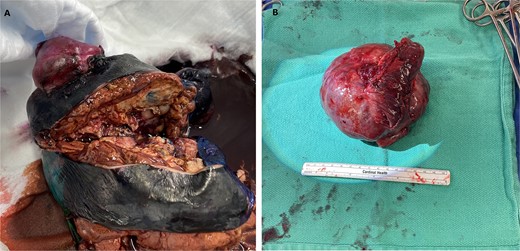

Ultimately, the patient had a right thoracotomy en bloc wedge resection of the right upper and lower lobe (Fig. 3A). The tumor was well-encapsulated and was 10.8 × 9.8 × 7.7 cm in size (Fig. 3B).

En bloc wedge resection of the right upper and lower lobe (A). The right upper lobe mass was a well-encapsulated tumor and measured 10.8 × 9.8 × 7.7 cm (B).

The patient convalesced well post-operatively and was discharged home. The patient gave informed consent for his case to be considered for publication. Final tumor pathology showed epithelioid malignancy in keeping with giant cell carcinoma, with lymphovascular invasion. Tumor margins were grossly clear. In contrast to our working diagnosis of metastatic recurrence of abdominal rhabdomyosarcoma, pathology results were in keeping with this GCCL being a new primary carcinoma.

Discussion

Given its rarity, there is limited existing literature on GCCLs. Population-based studies indicate a higher prevalence in males and current or former smokers, with a median age of diagnosis at 65 years [2, 3]. Less than 40% of GCCL cases present under the age of 60.

Our patient presented with an intracavitary solid-appearing mass within a fluid-containing apical bulla. GCCL typically presents as an intrapulmonary upper lobe mass of the lungs, though its presentation as a single air-containing cyst has been previously reported [4].

PSCs have been reported to be highly aggressive, with median overall survival being reported to be between 3 and 5 months, with GCCLs in particular having a 1- and 5-year survival of 21.7% and 7.9%, respectively [2, 5]. 60.3% of patients have metastatic disease at presentation [2]. Taking the aggressive nature of the disease into account and that diagnosis is made on resection specimens, its true prevalence may be underestimated. GCCL is poorly responsive to chemotherapy [2], though studies looking at immune checkpoint inhibitors show a potential increase in overall survival [5]. Post-operatively, our patient’s case was discussed with medical oncology for consideration of adjuvant therapies, though he likely would not have tolerated systemic therapies given his poor health at baseline.

Conclusions

In summary, we report the case of surgical resection of a rare GCCL in a 36-year-old male.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Patient consent

Obtained.