-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Konstantinos Seretis, Antonios Klaroudas, Vasiliki Galani, Georgios Papathanakos, Anna Varouktsi, Antigoni Mitselou, Anna Batistatou, Evangeli Lampri, Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: it might be rare but it exists, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 8, August 2023, rjad374, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad374

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS) is a rare mesenchymal tissue tumor. Its differential diagnosis from similar tumors, such as low differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma, desmoplastic melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), may be difficult, as they have similar clinical and histological presentation. We present a case of an 83-year-old man exhibiting an exophytic scalp lesion. Excision of the lesion was performed, ensuring clear surgical margins and pathologic examination revealed an invasive pleomorphic dermal sarcoma. This case highlights a rare case of a large pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and it discusses the histological, molecular features, its differential diagnosis and management of PDS.

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal neoplasms of the skin have a special interest, due to the difficulty in pathologic diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Mesenchymal skin tumors account only for 1% of major malignancies in adults. PDS is a very rare subtype of cutaneous tumors [1]. Most often it is witnessed in people with median age of 80 years and has a strong association with sun exposure [2]. The risk of local recurrence after excision is estimated around 20–30%, and they show metastatic potential to skin, lymph nodes and lung [3]. First line treatment is considered to be local surgical excision and other treatment options include cryotherapy and radiation [4].

A case of PDS in an elderly male is presented herein in accordance to the SCARE guidelines.

CASE REPORT

An 83-year-old Caucasian male presented with a 12-month history of a painless scalp lesion, during which period it gradually increased in size. Examination revealed a 40 mm, irregularly shaped, firm, exophytic nodule with overlying ulceration and hemorrhagic crust. Further examination showed no similar lesions or palpable lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1).

Given a high clinical suspicion of malignancy, the lesion was excised with 5-mm surgical margins, and the defect was afterwards repaired with a rotational flap under local tumescent anesthesia.

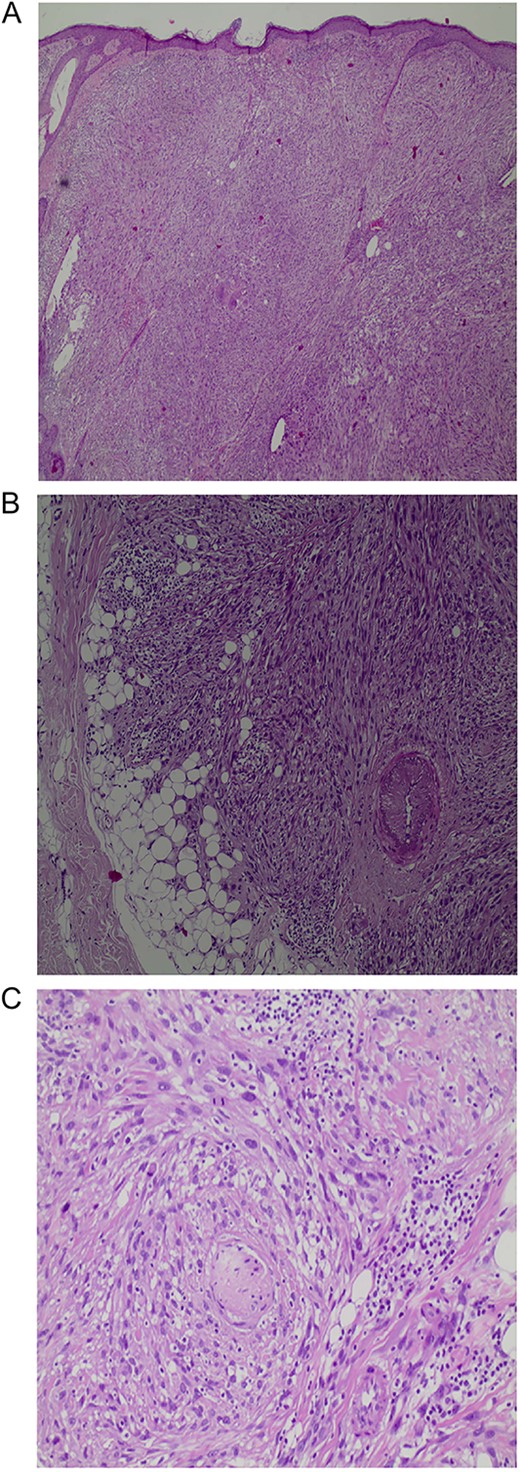

The histopathologic diagnosis was established based on the presence of irregular infiltrating spindle and pleomorphic tumor cells, which showed an invasive architectural pattern and extended to the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 2A). The tumor consisted of large polyhedral to cuboid tumor cells with moderate to abundant eosinophilic and rarely clear cytoplasm. Furthermore, the tumor cells demonstrated marked nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli as well as many mitotic figures, including atypical forms. Other observed features included epidermal ulceration and perineural invasion (Fig. 2B and C).

A: An expansile tumor in the dermis (H&E, original magnification X40). B: Involvement of subcutaneous fat (H&E, original magnification X100). C: Perineural invasion (H&E, original magnification X200).

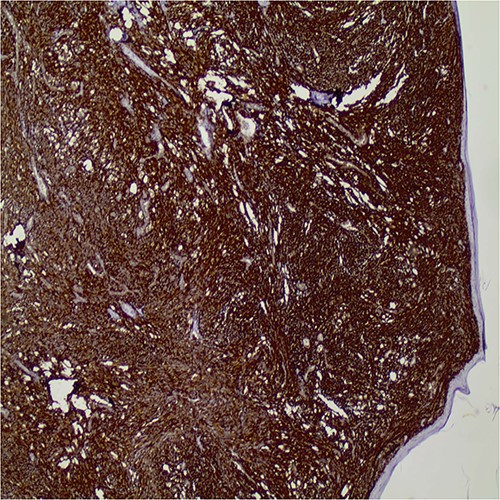

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells expressed diffuse CD10 positivity (Fig. 3), while they were negative for pancytokeratin, p63, keratin 5/6, MelanA. HMB45 and S-100 were also negative excluding the possibility of sarcomatous carcinoma and melanoma, respectively. The histopathologic and immunohistologic findings were consistent with invasive pleomorphic dermal sarcoma.

Diffuse CD10 expression by the tumor cells (original magnification X40).

Following the excision and histologic diagnosis, a head and neck ultrasound showed no signs of local tumor invasion or lymphadenopathy and the patient is currently on a 3-month basis follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Histologically, PDS is often presented as an ulcerated, poorly marginated and asymmetrical tumor with invasion into deep subcutaneous, muscular and/or fascial tissues. The tumors are cellular with pleomorphic atypical epithelioid or spindle cells, as well as multinucleated tumor giant cells [1, 4–9]. Tumor necrosis is observed in 53%, lymphovascular invasion in 26% and perineural infiltration in 29% [9]. The diagnosis of PDS is one of exclusion, requiring extensive use of immunohistochemistry. Negative staining against multiple cytokeratins, S100, desmin, HMB-45 and CD34 is a prerequisite for the diagnosis [9–11]. CD10 was expressed in all cases as stained [9].

The most difficult task is to distinguish it from the more AFX counterpart. The two entities share many morphological characteristics, such as tumor cell morphology, pleomorphism and atypical mitotic figures. Moreover, immunohistochemistry does not facilitate the diagnosis, as both of them express CD10 marker. The differential diagnosis is based on the morphological characteristics of PDS, such as the more aggressive histological features, the deeper subdermal involvement, the presence of lymphovascular or perineural invasion and/or necrosis [1, 5, 6]. In our case, the involvement of the deep subcutis and perineural invasion favor a diagnosis of PDS.

Moreover, little is known of the genetic events leading to the development of AFX and PDS. There are small studies, which identified UV-signature mutations in AFX [9, 12] and PDS [13].

AFX and PDS share many clinical, etiologic and histologic features, and they form a disease spectrum in which in a subset of tumor cells takes on an invasive phenotype and gain access to deep structures, vessels and nerves. This phenotype confers at least low-grade aggressive behavior with increased risk for local recurrence and even metastatic disease, so clear separation from AFX is necessary [14]. Designation as ‘undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of the skin’ may be equally acceptable, but it is important to avoid confusion with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of the subcutis or deeper soft tissues characterized by poor prognosis and outcome [15]. A cautious approach is necessary on superficial diagnostic biopsies, as a diagnosis of AFX should only be made when significant subcutaneous tissue is available for analysis. It would be safer, all AFX, be completely removed.

Despite the morphologic features of a high-grade sarcoma, the high incidence of tumor necrosis, and lympho-vascular invasion, the overall disease course is more consistent with a low-grade malignancy, a local recurrence rate of 28% and a metastatic rate of 10% [9].

PDS is considered to be on the same pathological spectrum as AFX, despite its different prognosis, and it is for this reason that it presents a diagnostic and clinical challenge [4, 7, 8]. While surgical removal remains the gold standard for the management of skin malignancy, there are no published guidelines, to the author’s knowledge, on surgical management and follow-up. In the literature, reported treatments for AFX include cryotherapy, radiation and surgical methods: wide local excision and Mohs micrographic surgery. Surgical excision seems to be a better treatment of choice. Cryotherapy has a greater risk of recurrence and metastasis, while irradiation has the risk of causing tumor DNA dysregulation, resulting in a more aggressive tumor [7]. In a meta-analysis of 23 studies comparing treatment for atypical fibroxanthoma, Mohs micrographic surgery was associated with a lower recurrence rate than wide local excision [8]. Complete surgical excision, with clear margins seems to be the best choice of treatment [4], while incomplete excision has a greater risk of local recurrence [3, 16]. Tardío et al. [2] showed a 20% rate of local recurrence after incomplete resection.

CONCLUSIONS

PDS is a rare, clinically aggressive mesenchymal malignancy. PDS shares many features with AFX and are assumed that they form a disease spectrum. Because of the rarity of PDS, the evidence regarding the surgical and adjuvant treatment requires further reporting and analysis. Currently, awareness should be raised to properly recognize and treat PDS.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was taken from the patient for the publication of this case report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

None.