-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lauren Wallace, James Gallagher, A delayed benign anastomotic stricture after anterior resection for sigmoid adenocarcinoma with concomitant collagenous colitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 3, March 2023, rjad103, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad103

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Benign anastomotic strictures most commonly occur within 3–12 months after anterior resection (AR) with chronic symptoms amenable to endoscopic treatment. This case describes an acute large bowel obstruction secondary to a severe delayed benign anastomotic stricture in a 74-year-old female who had previously underwent a laparoscopic AR for sigmoid adenocarcinoma 3 years prior. The pathophysiology of benign anastomotic strictures remains poorly understood. This case was likely multifactorial. Potential contributing factors include anastomotic ischaemia and concomitant collagenous colitis, with inflammation leading to fibrosis and stricture development. Surgical techniques to optimize anastomotic vascularity are important to consider, particularly in older patients with multiple co-morbidities.

INTRODUCTION

An acute large bowel obstruction (LBO) secondary to a benign anastomotic stricture (BAS) 3 years after anterior resection (AR) for colorectal cancer is discussed, with a focus on anastomotic ischaemia and a potential novel risk factor, concomitant collagenous colitis [1, 2].

CASE REPORT

A 74-year-old female presented to hospital with abdominal distension and obstipation. Three years before this admission, she underwent a laparoscopic high AR for sigmoid colon malignancy, found to be pT2N0 colorectal adenocarcinoma with complete resection and concurrent collagenous colitis. The high AR included a high IMA ligation at the aorta, splenic flexure mobilization and rectosigmoid circular stapled anastomosis above the peritoneal reflection. Her post-operative course was uncomplicated. She underwent yearly surveillance colonoscopies post-operatively, which demonstrated no disease recurrence or stricture, and she was asymptomatic on review 3 weeks prior to presentation. Her past medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

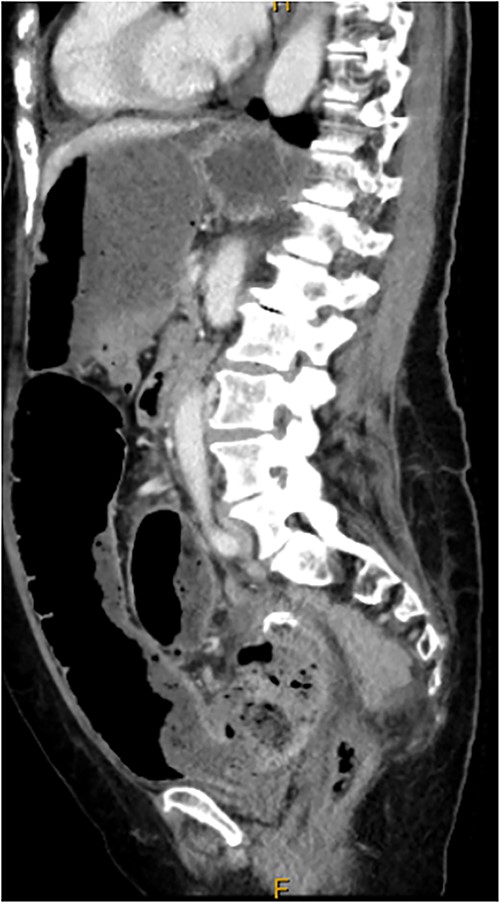

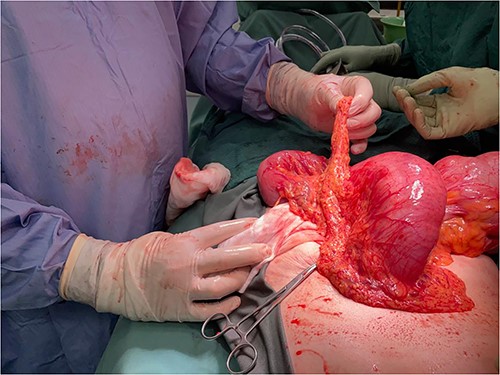

Computed tomography on current presentation demonstrated a mechanical LBO with a transition point at the anastomosis, with significant large bowel dilatation (see Figs 1 and 2). Flexible sigmoidoscopy revealed severe luminal narrowing at the anastomosis 20 cm from the anal verge prohibiting scope progression, with intra-luminal purulent discharge. She underwent a laparotomy and Hartmann’s procedure, with findings of severe colorectal anastomotic stenosis and a small, localized perforation. The colon proximal to the stricture was dilated but viable, with a caecal diameter of approximately 20 cm (see Figs 3 and 4). Histopathology confirmed a benign stricture with extensive fibrosis and a segment of full thickness necrosis and perforation. There was no evidence of malignancy and the post-operative recovery was unremarkable.

CT scan demonstrating stricture at site of sigmoid anastomosis and proximal dilatation and faecal loading.

CT scan demonstrating dilatated proximal large bowel and caecum (arrow).

Intra-operative findings, viable but severely dilated caecum and proximal colon.

Intra-operative findings, viable but severely dilated caecum and proximal colon.

DISCUSSION

The reported incidence of BAS after AR varies widely from 1 to 30% [3–6]. A common definition is an inability to pass a 12-mm sigmoidoscope through the anastomosis [6, 7]. These commonly occur within 3–12 months post-operatively, often presenting either asymptomatically on surveillance or with chronic symptoms of bowel habit changes, intermittent abdominal pain and distension or fractionated evacuation [3, 4, 6, 8]. The use of endoscopic dilatation, electrocautery or stricturoplasty is emphasized with success rates of 80–100% [3, 9]. Surgery is reserved for refractory, long segment strictures or emergency cases [4, 7, 8, 10]. This case presented three years after initial resection and anastomosis with acute LBO after two follow-up colonoscopies demonstrating no evidence of early stricture. This suggests a delayed, but rapid development of a severe stricture.

Several risk factors have been proposed but the pathophysiology of BAS remains poorly understood. Anastomotic leak, pelvic sepsis and radiotherapy have been frequently implicated by causing increased inflammation and fibrosis [3, 7, 8]. BAS has also been associated with reduced distance to anal verge, particularly when the anastomosis is below the peritoneal fold [3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12], and faecal diversion following anastomosis [12]. However, this is not corroborated in all studies [3–5]. Equally, an increased risk of BAS following stapled anastomosis has been reported [5, 11], with others failing to achieve significance [3].

The proposed mechanism for BAS is an exaggerated inflammatory response with increased collagen deposition [1, 11], and most risk factors cause inflammation, which is an independent risk factor for fibrosis and stenosis [5]. A five times higher incidence of BAS was found in those who underwent resection for diverticulitis compared with malignancy, suggesting diverticular inflammation predisposes to stricture formation [5]. The current case was for malignancy but the histopathology reported concomitant collagenous colitis, which is a type of microscopic colitis with findings of inflammatory changes in the mucosa and associated submucosal collagen fibre deposition [13]. Given the role of inflammation in BAS development, the presence of untreated collagenous colitis may have contributed to its formation in this case.

Ischaemia is also proposed to contribute to BAS formation [1]. AR surgical techniques are described including site of IMA ligation, either high at the level of the aorta or low, distal to the left colic artery origin, and splenic flexure mobilization to allow for tension-free anastomosis [1, 6, 8]. High IMA ligation results in reliance on the marginal artery proximally and inferior and middle rectal arteries distally to maintain blood supply to the colorectal anastomosis as there is limited collateralization at this site [1, 2]. Some hypothesize anatomical variations of the arcade may lead to ischaemia to the distal colon and rectum [1, 2]. It is reported that after high IMA ligation, tissue oxygen tension is maintained to the distal transverse and descending colon but reduced to the sigmoid colon [14]. Co-morbidities such as advanced age and atherosclerotic risk factors, particularly smoking, further compromise oxygenation to an anastomosis already reliant on a limited arterial supply [1, 2, 12, 15].

Although the importance of adequate vascular supply is logical and emphasized, results are conflicting with some finding no difference in rates of stricture formation between low and high IMA ligation [5, 6]. Indeed, some support the use of high IMA ligation in conjunction with splenic flexure mobilization to allow for improved left colon manoeuvrability to minimize anastomotic tension [6, 7]. In this case, a high IMA ligation and splenic flexure mobilization was performed but resection was limited with a rectosigmoid anastomosis. The high IMA ligation may have resulted in subtle ischaemia of the remaining sigmoid colon and anastomosis [14], contributing to stricture development. With proximal distension and faecal loading, the already ischaemic anastomosis may have been further compromised, resulting in an area of necrosis. Complete resection of the sigmoid colon with a descending colon to rectal anastomosis, as advocated by Hall et al. [14], may have allowed for both a high IMA ligation and splenic flexure mobilization creating a tension-free anastomosis with improved blood supply from the marginal artery to the descending colon [7, 14].

CONCLUSION

This delayed case of BAS after AR highlights its multifactorial nature including inflammation and ischaemia, and the need to optimize modifiable risk factors. Surgical techniques to optimize anastomotic vascularity while minimizing tension are also important to consider, particularly in older patients with increased cardiovascular risk factors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

No funding source for this article.