-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pierre-Emmanuel Goetz, Dana Dumitriu, Christine Galant, Pierre-Louis Docquier, Osteofibrous dysplasia-like adamantinoma of isolated fibula in a child mimicking chronic osteomyelitis with pathological fracture, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 6, June 2022, rjac196, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac196

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The occurrence of a pathological fracture in children requires a rigorous diagnostic approach in order to establish the etiology and to develop a precise therapeutic strategy. Several causes are associated with these fractures, the most frequent being benign tumors in children in developed countries and chronic osteomyelitis in developing countries. More rarely, malignant tumors must however always be considered. The differential diagnosis on imaging may be difficult to establish between bone tumors and chronic infection. Surgical biopsy is therefore often performed to establish the precise origin of the fracture. We report the case of an adamantinoma (osteofibrous dysplasia-like) of the fibula in a 7-year-old child, discovered during the management of a pathologic fracture. The presumed diagnosis before biopsy was chronic osteomyelitis. A 14-cm-resection of the affected fibula was performed with good functional result. Differential diagnosis between adamantinoma, osteofibrous dysplasia and osteofibrous dysplasia-like adamantinoma remains very challenging.

INTRODUCTION

Osteofibrous dysplasia (OFD) and ADamantinoma (AD) are rare primary osteofibrous tumors. AD accounts for only 0.1–0.5% of malignant bone tumors, whereas OFD accounts for ~0.2% of primary bone tumors [1, 2]. Both entities preferentially affect the tibial diaphysis [1] and their common manifestations are pain and/or pathological fracture [2, 3]. OFD tends to affect children younger than 10 years of age, whereas AD is more common in young adults between the ages of 25 and 35 years [1]. Radiologically similar, these tumors are characterized by intracortical, expansive osteolytic lesions in the mid-diaphysis, with varying degrees of osteolysis and osteosclerosis [2, 4]. Histologically, these two tumors have similar characteristics, with a similar cytokeratin immunologic profile and cytogenic aberrations [1].

Osteofibrous dysplasia-like adamantinoma (OFD/AD) is defined by the WHO classification as a subtype of adamantinoma [4]. Also called juvenile or differentiated AD, it affects children (like OFD) [2, 4].

We report the case of a difficult case of OFD/AD of the fibula in a 7-year old, which was initially misdiagnosed for a chronic osteomyelitis.

CASE REPORT

A 7-year-old boy presented with right lateral leg pain for 10 days, following a blow. Clinically, the middle third of the right fibula was painful to palpation and the child was limping. There was no redness, swelling, nor warmth. The patient had no fever. The only previous history was a periodontitis with fever that occurred 2 years earlier during a travel in Africa, treated with antibiotics. Blood tests were unremarkable, with a normal C reactive protein.

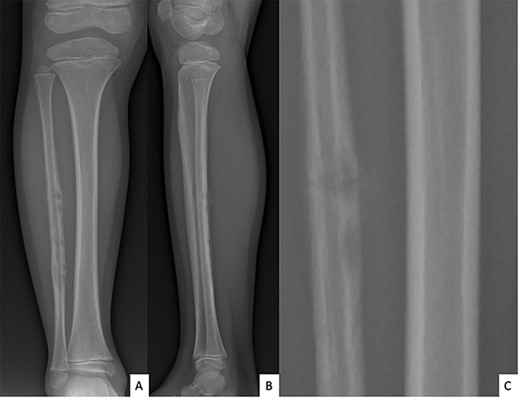

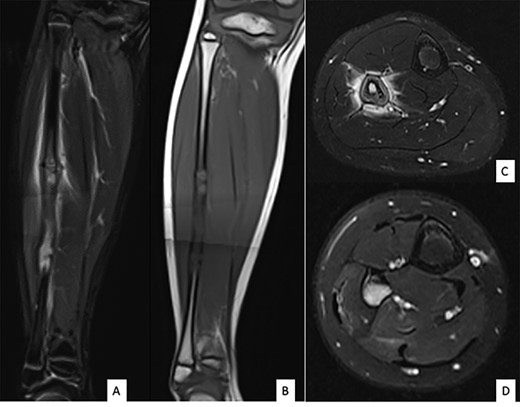

Ultrasound showed a diaphyseal subperiosteal hematoma of the fibula with cortical irregularities. The radiograph showed a pathological fracture, at the upper end of a cortical bone lesion of mixed osteolytic and osteoformative character with bone callus (Fig. 1). MRI showed a multifocal osteolytic cortical process extending along the fibular shaft, without tumor mass in the soft tissues with respect for the signal of the medullary cavity. The perilesional soft tissues were respected, but they appeared in strong hypersignal T2 and enhanced after injection of gadolinium (local inflammatory reaction or post-traumatic changes; Fig. 2).

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of right fibula showing pathological fracture on a cortical bone lesion of mixed osteolytic and osteoformative character with bone callus.

MRI of the right fibula: coronal MR STIR imaging (A); T1-weighted imaging (B); axial T2 FAT SAT section of the proximal part (C) and distal part (D) of the lesion. MRI shows areas of osteolysis around a medullary cavity narrowed by cortical thickening (sclerosis) and diffuse tissue inflammatory edema leading to suspicion of chronic osteomyelitis.

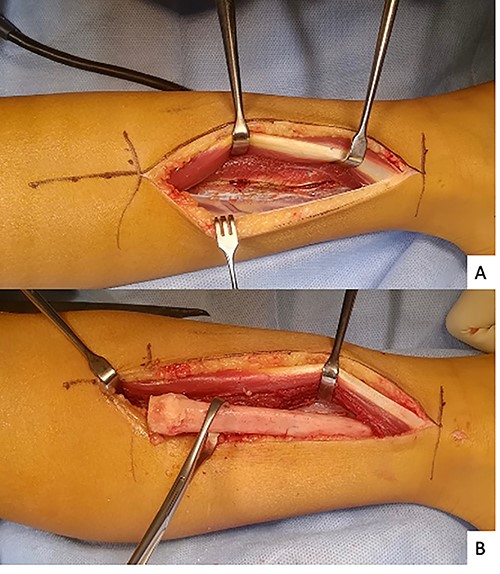

The initial diagnosis hypothesis was chronic osteomyelitis due to the history of periodontitis. A 14-cm fibulectomy was performed through a posterolateral approach (Figs 3 and 4) with periosteum preservation. A percutaneous cannulated screw was placed in the tibiofibular syndesmosis to prevent ascension of the lateral malleolus.

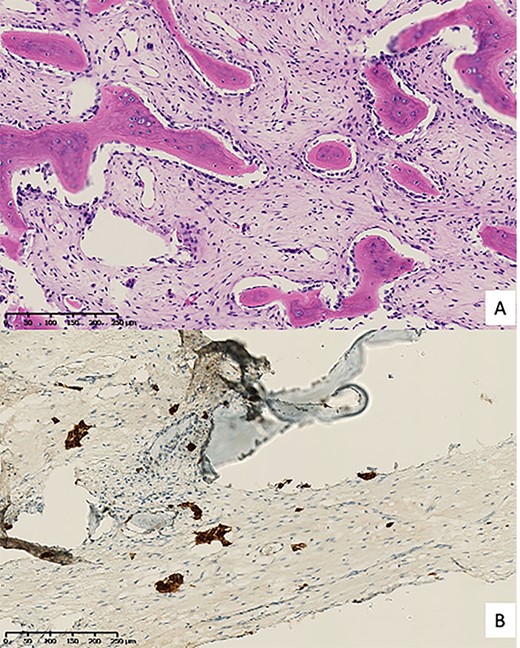

All bacteriological samples were negative. Anatomopathological analysis showed islands of cells that were positive for cytokeratin AE1/A3 but negative for CD68 and CD138 (Fig. 5). These findings argued for the diagnosis of OFD/AD rather than OFD. The day after the procedure, the child was allowed to walk with full weight bearing. The preservation of periosteum allowed rapid reconstruction of fibula (Fig. 6).

Pathological anatomy. (A) Hematoxylin & eosin staining; (B) Cell islands positive for cytokeratin AE1/A3 immunohistochemistry.

Anteroposterior radiograph and lateral view after right fibulectomy. (A): at 2-postoperative-weeks: preservation of the periosteum allowed progressive formation of new bone. (B) and (C): at 1-postoperative-year: a new fibula is reappeared. The syndesmosis screw broke with weight-bearing and only the fibular part of the screw was removed.

DISCUSSION

The differential diagnosis of a pathological fracture in a child, with multiple, intracortical, diaphyseal osteolytic lesions of a long bone, includes chronic osteomyelitis, the OFD-AD spectrum of diseases, eosinophilic granuloma and Ewing’s sarcoma [1, 5, 14].

In our case, based on the age, on the mixed aspect (osteoforming and osteolytic), on the diffuse inflammatory character as well as on the exclusively fibular localization, osteomyelitis was more probable than a tumor. Histological examination of the resected fibula allowed the diagnosis of OFD/AD. It remains very complex to distinguish OFD, AD and OFD/AD by histology. OFD is characterized by a predominant fibrous stroma with trabeculae of bone tissue surrounded by osteoblasts [2, 4, 6], whereas AD is characterized by predominant epithelial components associated with osteofibrous tissue. These epithelial cells are always positive for cytokeratin staining, and contain desmosomes, tonofilaments and microfilaments on electron microscopy [2, 4, 6]. However epithelial cells are also sometimes found in OFD as well, requiring the use of immunostaining. OFD is confirmed if epithelial cell groups are only identified by immunohistochemistry and not by hematoxylin & eosin staining [2]. On the contrary, OFD/AD requires the identification of these epithelial cells both by hematoxylin & eosin staining and immunohistochemistry [2].

Three different therapeutic attitudes are reported in the literature:

‘Immediate radical surgical resection of OFD and OFD/AD’ [7, 8] considering that OFD and AD/OFD are precursors to AD.

‘Simple monitoring of OFD and OFD/AD’ [9, 10] considering that OFD/AD will never progress to AD and considering the tendency of OFD to regress spontaneously after puberty [6]. Given the high risk of recurrence (25%) after curettage and local resection, surgical intervention is only necessary in case of extensive, painful and deforming lesions [6].

‘En bloc resection with wide margin of the OFD/AD, and surveillance of the OFD’ [11–13] considering OFD/AD as a histological subtype of AD [4, 12, 13]. A recent multicenter study proposed to reclassify OFD/AD as an aggressive local intermediate and not as a variant of adamantinoma [11]. The authors based their study on the results of surgical treatment of 128 OFD/AD and 190 AD. No metastasis was reported in the OFD/AD group, but there was a 22% local recurrence rate. They suggested that the risk of local recurrence would be higher in cases of pathologic fracture, in resection with contaminated margins, and in men.

Despite our initial diagnostic error, the one-stage fibulectomy was appropriate in our case. First, the patient presented with pain and a pathologic fracture, which according to Gleason et al. deserves surgical management, even in the case of OFD [6]. Second, the lesion only affected the isolated fibula, which does not require any bone reconstruction in a child, compared with the classical tibial lesions of the OFD-AD spectrum [1, 2, 7, 11–13]. However, in view of the high risk of recurrence reported by Schutgens et al. [11], a postoperative radio-clinical monitoring is needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors declare no conflict of interest related to this article.

References

- biopsy

- cancer

- fractures

- ameloblastoma

- bone neoplasms

- child

- developed countries

- developing countries

- differential diagnosis

- fibula

- pathological fractures

- surgical procedures, operative

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- benign neoplasms

- osteomyelitis, chronic

- osteofibrous dysplasia

- causality

- dysplasia

- chronic infection