-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jessica Shields, Jared Robichaux, Kevin Morrow, Clifford Crutcher, Gabriel Tender, Rupture of a superficial temporal artery pseudoaneurysm following craniotomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 9, September 2021, rjab379, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab379

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery (STA) is a rare entity that has been reported in the literature after trauma or iatrogenic injuries. We describe a unique case of STA pseudoaneurysm rupture and the clinical sequelae associated with its rupture. We report a case of pseudoaneurysm rupture of the STA that occurred 14 days after craniotomy for cerebrospinal fluid leak repair. We also review the literature, diagnosis and treatment of external carotid artery aneurysms. Rupture of a STA pseudoaneurysm is a previously unreported and serious complication that must be quickly recognized in order to control hemorrhage that may have life threatening complications.

INTRODUCTION

The superficial temporal artery (STA) is a terminal branch of the external carotid artery, divided into frontal and parietal branches and is frequently encountered in cranial surgery. Only a handful of STA pseudoaneurysms (PA) have been reported, the majority are the result of blunt or penetrating trauma presenting as a unilateral pulsatile scalp mass [1–6]. Iatrogenic PA of the STA have also been reported in the literature and are thought to be due to partial injury of the intimal wall during manipulation or coagulation [7].

We describe a case of a ruptured STA PA that caused significant subgaleal and subdural hematoma. Consideration of post-traumatic and iatrogenic PA in the differential diagnosis of polytrauma patients should be considered. We also review PA of the external carotid artery as a rare but important diagnostic consideration.

CASE PRESENTATION

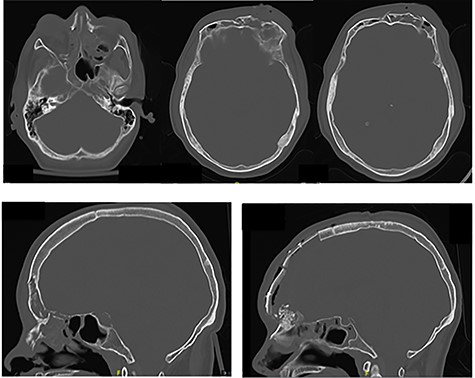

A 38-year-old man presented to the emergency department at our level-one trauma center following a high-speed motor vehicle accident. Initial trauma workup revealed significant anterior and basilar skull base fractures (Fig. 1) as well as multiple orthopedic injuries (pubic ramus fracture, clavicular and humerus fracture) and intrathoracic and abdominal injuries (piriformis muscle contusion, retrosternal hematoma and pulmonary contusion). He was ultimately hemodynamically stabilized and underwent orthopedic repair. Throughout his hospitalization, the patient’s neurologic status remained stable. He was closely monitored by the neurosurgery and plastics services for development of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak.

(A, B) Preoperative CT imaging showing extensive anterior and skull base fractures. The patient ultimately developed a cerebrospinal fluid leak and required operative repair. (C) Postoperative CT imaging showing bifrontal craniotomy repair as well as repair of the anterior skull base.

On hospital Day 5, the patient developed a profuse CSF leak requiring a lumbar drain was placed. Subsequently, after failure of the lumbar drain to completely stop the rhinorhea in 48 hours, the patient was taken to the operating room with both plastic surgery and neurosurgery for a bifrontal craniotomy for cranialization of the frontal sinus via split calvarial bone graft and periosteal flap. At that time he also underwent repair of naso-orbitoethmoidal fractures (Fig. 1A and C). His postoperative course was uncomplicated. On hospital Day 9 (postoperative Day 2), the lumbar drain was clamped and removed after there was no further evidence of CSF leak in 24 hours. He was ultimately discharged on hospital Day 10.

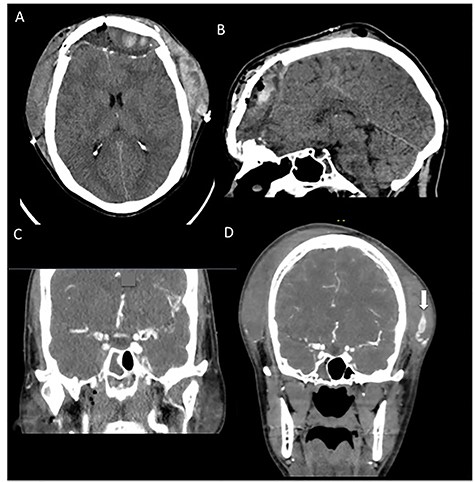

On postoperative Day 14, the patient presented to the emergency department with sudden onset of a severe headache and significant facial swelling. Imaging showed large bifrontal subdural hematoma with an associated large subgaleal hematoma (Fig. 2A, B). Computed tomography (CT) angiography was performed due to concern for vascular cause secondary to sudden onset in the setting of recent trauma and showed a 6 mm × 18 mm left STA PA (Fig. 2D) that was presumed to have ruptured due the degree of his extracranial and intracranial hemorrhage. He was taken back emergently for revision craniotomy to evacuate the subgaleal and subdural hematoma. The aneurysm was ligated intraoperatively. He tolerated the procedure well and was ultimately discharged with no outward complication at follow-up. Repeat CT angiography did not show any persistent PA.

CT angiography taken at 2 weeks postoperatively when patient returned with sudden onset of facial swelling and significant headache. (A, B) Noncontrasted CT of the head showing significant subgaleal hematoma and adjacent bifrontal subdural hematoma with associated mass effect. (C) Prior trauma imaging (CT angiography of the neck) from initial hospitalization showing no evidence of STA pseudoaneurysm. (D) CT angiography showing a large (18 mm × 7 mm) left STA pseudoaneurysm (white arrow).

DISCUSSION

This case summarizes significant clinical consequence of PA rupture. In our patient it is unclear whether the PA developed from the blunt trauma or was iatrogenic due to craniotomy for CSF leak repair. The patient had an initial CT angiography that did not show any evidence of STA injury leading us to believe it was likely iatrogenic in nature. The largest case reports of external carotid artery (ECA) PA’s describe STA PA’s presenting as a pulsatile mass in the temporal region [4, 5]. Other single reported cases of STA aneurysms describe both incidental and post-traumatic origin; however, they typically present in a similar fashion.

External carotid artery PA’s are rare and are an important diagnostic consideration as illustrated in this case. Case reports are summarized in Table 1. Most commonly, external carotid artery PA’s have been reported following trauma (especially penetrating trauma). Other causes cited include iatrogenic, inflammation, infection and vasculitis [5, 8–12]. The most common vessels implicated are the STA, internal maxillary artery and facial artery. The concern with rupture of an ECA PA is that it may cause immediate airway compromise. Doppler ultrasound is a common tool for evaluation of a PA, however it can be supplemented by contrasted CT angiography in severe trauma cases, such as the case described. Formal diagnostic subtraction angiography then is utilized for treatment after the PA has been diagnosed by these methods.

| . | N . | Presentation . | Diagnosis . | Treatment . | Cause . | Location . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [4] | 17 | N = 13 pulsatile mass N = 2 parotid bleeding (after parotid surgery) N = 1 epistaxis after intranasal surgery N = 1 bleeding R neck/ECA after stabbing | Ultrasound | Embolization | N = 8 penetrating trauma N = 5 blunt trauma N = 1 idiopathic N = 2 parotid surgery N = 1 nasal surgery | N = 6 STA (nonruptured) N = 4 internal maxillary N = 3 ECA N = 2 superior thyroid artery |

| Cox et al. [5] | 11 | N = 9 pulsatile mass N = 1 bleeding (maxillary, ECA) N = 1 neck swelling (facial artery) | CTA, ultrasound | 6 Embolization, 2 stents, 2 ligation, 1 observation | Penetrating trauma | N = 1 STA (nonruptured) N = 2 lingual N = 2 maxillary N = 1 facial N = 1 ECA N = 1 vertebral N = 1 ICA |

| Pipinos et al. [1] | 6 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Tekin et al. [2] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Zhang et al. [3] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CT angiography | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Isaacson et al. [6] | 3 | Pulsatile mass Surveilance imaging | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation vs embolization | N = 2 blunt trauma N = 1penetrating trauma | STA |

| Brandt et al. [10] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation | Parotid surgery | STA |

| Choi et al. [8] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation | Oral surgery | Facial artery |

| Murono et al. [9] | 1 | Oral bleeding | DSA | Embolization | Intra-arterial chemotherapy | Lingual artery |

| Pukenas et al. [11] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Embolization | Molar extraction | Facial artery |

| Hacein-Bey et al. [14] | 1 | Vagal, accessory nerve palsies | CTA, DSA | Stent and embolization | Le Fort I osteotomy | High cervical ICA |

| . | N . | Presentation . | Diagnosis . | Treatment . | Cause . | Location . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [4] | 17 | N = 13 pulsatile mass N = 2 parotid bleeding (after parotid surgery) N = 1 epistaxis after intranasal surgery N = 1 bleeding R neck/ECA after stabbing | Ultrasound | Embolization | N = 8 penetrating trauma N = 5 blunt trauma N = 1 idiopathic N = 2 parotid surgery N = 1 nasal surgery | N = 6 STA (nonruptured) N = 4 internal maxillary N = 3 ECA N = 2 superior thyroid artery |

| Cox et al. [5] | 11 | N = 9 pulsatile mass N = 1 bleeding (maxillary, ECA) N = 1 neck swelling (facial artery) | CTA, ultrasound | 6 Embolization, 2 stents, 2 ligation, 1 observation | Penetrating trauma | N = 1 STA (nonruptured) N = 2 lingual N = 2 maxillary N = 1 facial N = 1 ECA N = 1 vertebral N = 1 ICA |

| Pipinos et al. [1] | 6 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Tekin et al. [2] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Zhang et al. [3] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CT angiography | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Isaacson et al. [6] | 3 | Pulsatile mass Surveilance imaging | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation vs embolization | N = 2 blunt trauma N = 1penetrating trauma | STA |

| Brandt et al. [10] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation | Parotid surgery | STA |

| Choi et al. [8] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation | Oral surgery | Facial artery |

| Murono et al. [9] | 1 | Oral bleeding | DSA | Embolization | Intra-arterial chemotherapy | Lingual artery |

| Pukenas et al. [11] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Embolization | Molar extraction | Facial artery |

| Hacein-Bey et al. [14] | 1 | Vagal, accessory nerve palsies | CTA, DSA | Stent and embolization | Le Fort I osteotomy | High cervical ICA |

| . | N . | Presentation . | Diagnosis . | Treatment . | Cause . | Location . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [4] | 17 | N = 13 pulsatile mass N = 2 parotid bleeding (after parotid surgery) N = 1 epistaxis after intranasal surgery N = 1 bleeding R neck/ECA after stabbing | Ultrasound | Embolization | N = 8 penetrating trauma N = 5 blunt trauma N = 1 idiopathic N = 2 parotid surgery N = 1 nasal surgery | N = 6 STA (nonruptured) N = 4 internal maxillary N = 3 ECA N = 2 superior thyroid artery |

| Cox et al. [5] | 11 | N = 9 pulsatile mass N = 1 bleeding (maxillary, ECA) N = 1 neck swelling (facial artery) | CTA, ultrasound | 6 Embolization, 2 stents, 2 ligation, 1 observation | Penetrating trauma | N = 1 STA (nonruptured) N = 2 lingual N = 2 maxillary N = 1 facial N = 1 ECA N = 1 vertebral N = 1 ICA |

| Pipinos et al. [1] | 6 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Tekin et al. [2] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Zhang et al. [3] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CT angiography | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Isaacson et al. [6] | 3 | Pulsatile mass Surveilance imaging | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation vs embolization | N = 2 blunt trauma N = 1penetrating trauma | STA |

| Brandt et al. [10] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation | Parotid surgery | STA |

| Choi et al. [8] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation | Oral surgery | Facial artery |

| Murono et al. [9] | 1 | Oral bleeding | DSA | Embolization | Intra-arterial chemotherapy | Lingual artery |

| Pukenas et al. [11] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Embolization | Molar extraction | Facial artery |

| Hacein-Bey et al. [14] | 1 | Vagal, accessory nerve palsies | CTA, DSA | Stent and embolization | Le Fort I osteotomy | High cervical ICA |

| . | N . | Presentation . | Diagnosis . | Treatment . | Cause . | Location . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [4] | 17 | N = 13 pulsatile mass N = 2 parotid bleeding (after parotid surgery) N = 1 epistaxis after intranasal surgery N = 1 bleeding R neck/ECA after stabbing | Ultrasound | Embolization | N = 8 penetrating trauma N = 5 blunt trauma N = 1 idiopathic N = 2 parotid surgery N = 1 nasal surgery | N = 6 STA (nonruptured) N = 4 internal maxillary N = 3 ECA N = 2 superior thyroid artery |

| Cox et al. [5] | 11 | N = 9 pulsatile mass N = 1 bleeding (maxillary, ECA) N = 1 neck swelling (facial artery) | CTA, ultrasound | 6 Embolization, 2 stents, 2 ligation, 1 observation | Penetrating trauma | N = 1 STA (nonruptured) N = 2 lingual N = 2 maxillary N = 1 facial N = 1 ECA N = 1 vertebral N = 1 ICA |

| Pipinos et al. [1] | 6 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Tekin et al. [2] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Zhang et al. [3] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CT angiography | Ligation, resection | Blunt trauma | STA |

| Isaacson et al. [6] | 3 | Pulsatile mass Surveilance imaging | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation vs embolization | N = 2 blunt trauma N = 1penetrating trauma | STA |

| Brandt et al. [10] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation | Parotid surgery | STA |

| Choi et al. [8] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Ligation | Oral surgery | Facial artery |

| Murono et al. [9] | 1 | Oral bleeding | DSA | Embolization | Intra-arterial chemotherapy | Lingual artery |

| Pukenas et al. [11] | 1 | Pulsatile mass | Ultrasound, CTA | Embolization | Molar extraction | Facial artery |

| Hacein-Bey et al. [14] | 1 | Vagal, accessory nerve palsies | CTA, DSA | Stent and embolization | Le Fort I osteotomy | High cervical ICA |

Treatment for aneurysms of the ECA include conservative, surgical and endovascular methods depending on size, risk of rupture, adjacent structures and clinical symptomology. Conservative management typically includes observation and compression [13]. Previous reports demonstrate spontaneously resolving iatrogenic PA in 89% [14, 15]. The risk of conservative management is that the aneurysm increases in size, compression of surrounding structures causing neural dysfunction or rupture [3–5].

Embolization of the aneurysm or sacrifice of parent vessel is an additional option [4, 5]. Wang et al. also describe percutaneous embolization of STA PA due to the difficulty accessing this vessel angiographically. In our patient, surgical management of the aneurysm was the only available option due to the rupture and intracranial extension requiring decompression.