-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mark Johannes Maria Zee, Barbara Catharina van Bemmel, Jos Jacobus Arnoldus Maria van Raay, Massive osteolysis due to galvanic corrosion after total knee arthroplasty: a rare cause for early revision?, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 2, February 2020, rjaa002, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa002

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 66-year-old male underwent a total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis after previous anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. Seven years postoperatively, a symptomatic large lytic lesion was present surrounding the tibial stem. A titanium interference screw, which was used prior to fixate the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) graft, was in direct contact with the tibial component. Galvanic corrosion may have attributed to the development of the lytic lesion. It is advised to remove any metal hardware in the vicinity of joint prosthesis in order to prevent a possible galvanic corrosive reaction.

INTRODUCTION

In the presence of two different metal alloys, galvanic corrosion can occur [1]. Each metal has its own electrode potential that corresponds to its place in the electrochemical series. When different metals are placed in contact with an electrolyte solvent, galvanic corrosion may occur. The weaker electrochemical metal will function as an anode and will release its ions into the electrolyte solvent. This process is called galvanic corrosion [2]. In this report, a case is described in which two different metal implants were in close proximity, potentially leading to galvanic corrosion and subsequent massive osteolysis, component loosening and revision of the knee arthroplasty.

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old male underwent a cemented, posterior cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty for secondary osteoarthritis after previous transtibial anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. The ACL reconstruction was performed using titanium interference screws for graft fixation. Preoperative radiographic images showed Kellgren–Lawrence grade II–III osteoarthritis with the interference screws in place, without any signs for osteolytic lesions.

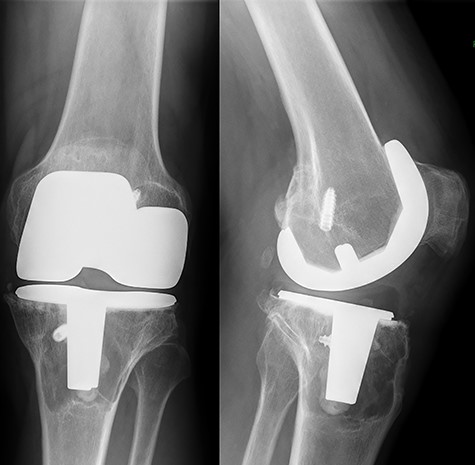

A cemented cobalt–chromium alloy knee arthroplasty from the anatomically graduated components V2 system (Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA) was implanted using Palacos R + G cement (Heraeus Medical GmbH, Wehrheim, Germany). The one-piece design of the tibial component includes a fixed polyethylene bearing that is molded to the cobalt chromium baseplate during the manufacturing process. During surgery, after resection of the tibial plateau, the tibial titanium interference screw was observed and left in place since it did not interfere with correct placement of the tibial stem. Postoperative recovery went uneventful. Seven years postoperatively, the patient was referred to the outpatient department of our institution complaining of pain on the anteromedial side of the proximal tibia. Previous history included a papillary urothelial carcinoma that was curatively treated 2 years earlier, and a recent discovery of a carcinoma in situ of the bladder was yet to be treated. On physical examination, no signs of effusion and a good range of motion with a flexion of 130° and full extension were present. There was a thickening of the soft tissue present over the anteromedial side of the proximal tibia, which was painful on palpation. Axial load was painful. An X-ray of the left knee showed the titanium interference screw in direct contact with the tibial stem of the prosthesis (see Fig. 1). Additional imaging consisted of a computed tomography (CT) scan and Technetium99 bone scintigraphy. Both revealed a large lytic, sclerotic enlined, lesion surrounding the tibial stem. The direct contact between the interference screw and the tibial stem was confirmed by CT. Serum inflammatory markers were normal as well as serum levels of cobalt and chromium. Diagnosed with aseptic loosening of the tibial component, the patient was scheduled for revision surgery.

Preoperative standing X-ray of the left knee. A large lytic lesion is seen surrounding the tibial component.

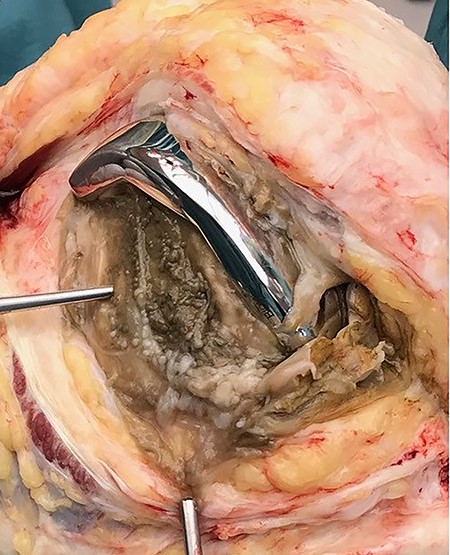

Intraoperatively, the synovium was stained gray (see Fig. 2). The tibial component was loose and easily extracted. Wear of the polyethylene bearing was present, mainly involving the posterolateral part of the fixed polyethylene bearing (see Fig. 3). No wear through or metal on metal contact was observed. The femoral component was well-fixed. After removal of the tibial component, a large cavity was opened that was filled with a yellow jelly-like substance (see Fig. 4). The titanium screw could easily be removed. Circumferential cortical support was present. The cavity was filled with a cancellous bone allograft. After bone impaction grafting was completed, a stemmed tibial and femoral component using the LEGION revision total knee system (Smith and Nephew, London, UK) was cemented in place. Intraoperative cultures remained negative. Histologic analysis of the synovium showed extensive reactive changes with giant cells reacting to foreign material, as seen in polyethylene wear disease. No metal particles were seen. There were no signs for the presence of a tumor or metastasis. The aforementioned yellow-like substance showed no remnants of cells.

Intraoperatively gray staining of the synovium was encountered.

The tibial bearing showed wear mainly involving the posterolateral corner.

After removal of tibial component a large pseudotumor was observed in the proximal tiba.

At a follow-up of 3 months postoperatively patient had regained a good range of motion in absence of pain.

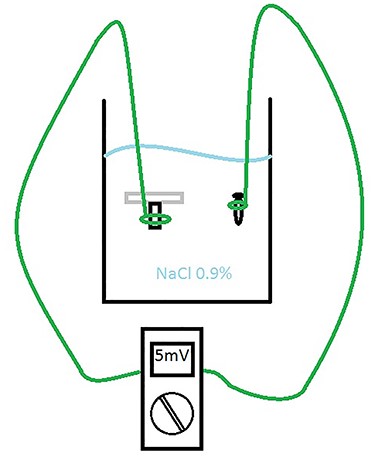

The explanted prosthesis was retrieved for further analysis. To support the diagnosis of galvanic corrosion both the tibial component and the interference screw were placed in a 0.9% sodium chloride solution and connected to a voltmeter (see Fig. 5). A current of 5 mV was measured, supporting the theory of an electrochemical reaction that had taken place, possibly leading to galvanic corrosion.

Test setup analyzing for a microcurrent between the tibial component and titanium interference screw.

DISCUSSION

A literature search revealed several cases of massive osteolysis after total knee arthroplasty, all of which are associated with significant amounts of polyethylene wear and metal on metal articulation of the knee arthroplasty [3–7]. To our knowledge, massive osteolysis around a total knee arthroplasty due to galvanic corrosion has not been described before.

In this case, there was no wear through of the bearing and no metal on metal contact between the femoral and tibial component present.

In the presence of galvanic corrosion, a microcurrent is established between the two metals. Hypothetically, this current can lead to cell necrosis, explaining the absence of cell remnants during histologic analysis of the osteolytic lesion.

On a macroscopic level, the interference screw showed minor damage on the tip of the screw, there were no scratches observed on the tibial component. The tibial component and interference screw were not analyzed on a microscopic level by a scanning electrochemical microscopy.

Although hypothetically, in this case the massive osteolysis most likely was the result of the combination of galvanic corrosion and polyethylene wear of the bearing.

In orthopedic surgery, it is not uncommon to have successive surgical procedures, which may include the use of implantable hardware such as plates, screws and prostheses. Although in this case a causative relation between the massive osteolysis and galvanic corrosion cannot be proven, the authors advocate caution when combining different metallic components in a patient. It is advised to remove any metal hardware in the vicinity of joint prosthesis in order to prevent a possible galvanic corrosive reaction. This is even recommended in cases where hardware does not hamper implantation of the prosthesis. Failure to remove metal hardware in the vicinity of a joint prosthesis may attribute to galvanic corrosion that may lead to complications as pain, fractures and early revision.