-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marco Nardini, Emmanuel Katsogridakis, Marcello Migliore, Joel Dunning, Chylopericardium with symptoms of tamponade on the grounds of extensive neck vein thrombosis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 1, January 2017, rjw242, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw242

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chylopericardium is a recognized complication of thoracic trauma, surgery or malignancy. Idiopathic or primary presentations, however, are rarely encountered in clinical practice. The severity of its presentation varies from the complete absence of symptoms to cardiac tamponade. We present the case of a 23-year-old woman with chylopericardium and extensive neck vein thrombosis that was managed surgically with a pericardial window.

INTRODUCTION

Chylopericardium is a rare clinical entity that is characterized by the presence of chyle in the pericardial cavity [1]. Its association with lymphangiomas, cystic hygromas, thoracic and cardiac surgery, trauma, radiation and malignancy is well reported [2, 3]. However, primary chylopericardium, in which there is absence of known precipitating factors, is rarely encountered in clinical practice.

The severity of clinical manifestations of chylopericardium is varied and may range from the complete absence of symptoms to cardiac tamponade, and thus a high index of suspicion is required for the prompt recognition of the underlying diagnosis and management of its sequalae [2].

In this report, we present a case of chylopericardium in a 23-year-old woman, presenting with acute shortness of breath in the background of extensive neck vein and superior vena cava (SVC) thrombosis, of unknown aetiology.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old woman was admitted with dyspnoea and hypotension of recent onset. Her past medical history was significant only for endometriosis. She had been admitted into hospital 2 weeks earlier due to a community acquired pneumonia with parapneumonic collection, which required drainage and intravenous antibiotics. Her initial recovery was uneventful and thus the patient was discharged home a few days later. On this admission, her initial work-up with routine blood tests and biochemistry was unremarkable.

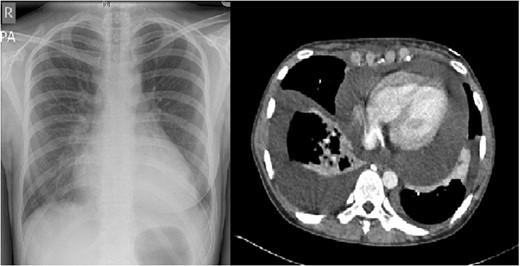

Pre-operative chest radiograph and axial view of a CT thorax, demonstrating a large pericardial collection.

After pericardiocentesis, the patient had recurrence and was thus taken to theatre, underwent an anterior left mini-thoracotomy, through which a pericardial window was fashioned, 600 ml of chyle were collected and an 18 Fr drain was placed in the pleural cavity. Her postoperative course was uneventful, drain removed on Day 3, and she was discharged home as the collection and her symptoms had resolved. She remains symptom and collection free at 1 year postoperatively, with no evidence of recurrence on follow-up chest radiographs.

DISCUSSION

The association of chylopericardium with trauma, previous thoracic or cardiac surgery, congenital lymphangiomas, radiation and malignancy is well recognized [2–5]. However, primary chylopericardium is a clinical entity that is more rarely encountered and only diagnosed if all known precipitants have been excluded [6–8].

Its pathophysiology remains controversial, and is thought to be related to either elevated pressure in the thoracic duct, or to abnormal communications between the thoracic duct and the lymphatics of the pericardium [3, 6]. Clinical manifestations are varied as it is the age spectrum of patients affected, with reports of chylopericardium in neonates through to older adult [8].

The imaging modalities that can be used to ascertain the underlying cause, with varying specificity and sensitivity, include lymphangioscintigraphy, lymphangiography, monitoring of chest radioactivity after oral intake of I-triolein and observation of the distribution of Sudan III dye in the pericardial cavity after ingestion [2, 3]. However, the diagnosis still relies on the cytology, chemistry and microbiology of pericardial aspirate, obtained via pericardiocentesis.

The management of this condition though controversial has two main therapeutic aims. The first is the prevention of cardiac tamponade. This can be achieved via pericardiocentesis or surgically with the formation of a pericardial window/partial pericardiectomy, which can be combined with ligation of the thoracic duct and by conventional open methods or via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). The second aim is the avoidance of metabolic, nutritional and immunological compromise, resulting from the loss of chyle, via a diet rich in medium chain triglycerides or, if necessary total parenteral nutrition [2, 9, 10].

In this instance, we decided to employ a stepwise approach to the management of this patient. As pericardiocentesis is associated with a high incidence of recurrence, we opted for the pericardial window, combined with dietetic input to address the patient's nutritional requirements. The patient having been informed of her options, opted for the option of conventional surgery in preference to VATS, a method that can also be safely used for the same purpose [2–4].

The patient remains symptom-free a year postoperatively, and has been put on a surveillance programme with frequent follow-up.

In conclusion, chylopericardium is a clinical entity that is not frequently encountered in the daily clinical practice and requires a high index of suspicion. Its management needs to address both the prevention of cardiac tamponade and the correction of nutritional and metabolic compromise that can ensue.