-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Stephen Honeybul, Coexistence of an intracranial meningioma and an arteriovenous malformation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 6, June 2015, rjv061, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjv061

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The occurrence of a primary brain tumour in association with a cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a recognized but rarely reported finding. A 56-year-old female presented following a single tonic clonic seizure. Radiological investigations revealed a left posterior frontal parafalcine meningioma and a left parietal AVM. Both were uneventfully resected. Whether there is a causal relationship is unproven, however, this case report might lend some support to this hypothesis given the relatively close proximity of the two lesions.

INTRODUCTION

The occurrence of a primary brain tumour in association with a cerebral arteriovenous malformation is a recognized but rarely reported finding [1–4]. Fine and Gonski reported the coexistence of an intraventricular oligodendroglioma and a right parietal arteriovenous malformation (AVM), and there has since been over 50 cases reported [5]. Some of these cases have been meningiomas and the question has arisen as to whether this is a chance association or whether there may be a causal relationship given that the lesions are often in close spatial proximity [6, 7]. This case report might lend some support to this hypothesis given the relatively close proximity of a left posterior frontal parafalcine meningioma and a left parietal AVM.

CASE REPORT

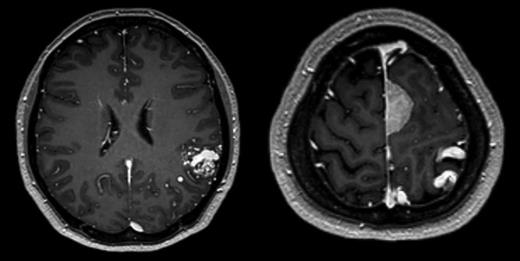

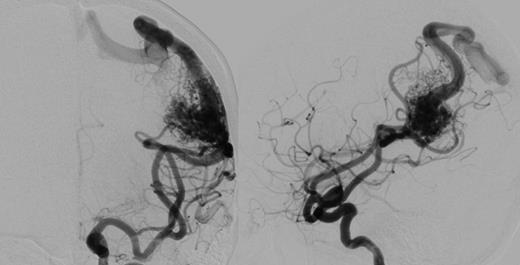

A 56-year-old female presented following a single tonic clonic seizure. Neurological examination was unremarkable. An MRI scan revealed a left posterior frontal parafalcine meningioma with vasogenic oedema in the precentral gyrus with a localized mass effect. In addition, there was a 2.6-cm left parietal AVM located in the left angular/supramarginal gyrus (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of prior haemorrhage. Cerebral angiography confirmed the arterial supply to be predominantly from enlarged parietal and angular branches of the left middle cerebral artery. Venous drainage was superficial into an enlarged vein of Trolard towards the superior sagittal sinus (Fig. 2).

Axial T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced MRI showing a 2.6-cm left parietal AVM located in the left angular/supramarginal gyrus (left) and an enhancing posterior frontal parafalcine meningioma in close association with the superficial draining veins of the AVM.

Cerebral angiogram, antero-posterior (left) and lateral (right) revealing a 2.6 × 2.6 × 3.4 cm sulcal type AVM in the left parietal region. Arterial supply is from enlarged parietal and angular branches of the left middle cerebral artery. Venous drainage is superficial into an enlarged vein of Trolard towards the superior sagittal sinus.

The patient gave a history of increasing severe early morning headaches over the previous 6–9 months and because there was evidence of significant localized mass effect, it was decided to initially resect the meningioma. This was undertaken uneventfully and she made a full recovery. Thereafter, she was counselled regarding the management options for the AVM and was offered either conservative management, stereotactic radiosurgery, or surgical resection. She elected for surgical resection and this was undertaken uneventfully 6 months after her initial surgery. The patient made a full recovery following 6 weeks of mild expressive dysphasia

DISCUSSION

Whether there is any connection between the occurrence of vascular malformations and the development of an intracranial meningioma is debateable. The incidence of AVMs is in the region of 1 in 100 000 and the incidence of meningiomas is in the region of 5.04 and 2.46 per 100 000 for females and males, respectively. Given that they are both relatively uncommon occurrences, finding both pathologies in one patient may be entirely coincidental. Conversely, this type of association may actually be under reported; if there is a causal relationship, the pathogenesis is unknown.

Cushing and Eisenhardt suggested that chronic irritation of the arachnoid cells caused by the increased blood flow may initiate a pathological process [8].

However, more recently, advances in cellular biology have enabled other pathophysiological mechanisms to be proposed. The traditional teaching is that an AVM is a static congenital lesion of embryonic origin. However, there have been reports of de novo formation, radiographic growth, and recurrence after successful obliteration, which would seem to challenges this traditional assumption. Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated evidence of increased endothelial cell turnover, elevated proangiogenic cytokine secretion (including angiopoietin-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor), and increased angiogenic receptor expression. These findings would seem to indicate that AVMs represent a dynamic pathological process, involving abnormal angiogenesis and active vascular remodelling [9, 10].

Individually, none of these findings provide sufficient direct evidence to imply causation of pathology in close proximity; however, it would certainly represent a number of potential pathophysiological mechanisms and as such is an area of research potential.

Notwithstanding either a coincidental or causal relationship, the management of these lesions would appear to be to treat each lesion on its merits. In this particular, the rationale to treat the meningioma first was to reduce the mass effect. Once the patient had adequately recovered and the vasogenic oedema had subsided, it was possible to safely and successfully resect the AVM.