-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hasanga Jayasekera, Kym Gorissen, Leo Francis, Carina Chow, Diffuse large B cell lymphoma presenting as a peri-anal abscess, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2014, Issue 6, June 2014, rju035, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju035

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A non-healing peri-anal abscess can be difficult to manage and is often attributed to chronic disease. This case documents a male in his seventh decade who presented with multiple peri-anal collections. The abscess cavity had caused necrosis of the internal sphincter muscles resulting in faecal incontinence. Biopsies were conclusive for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. A de-functioning colostomy was performed and the patient was initiated on CHOP-R chemotherapy. Anal lymphoma masquerading as a peri-anal abscess is rare. A high degree of suspicion must be maintained for an anal abscess which does not resolve with conservative management.

INTRODUCTION

Peri-anal abscesses tend to form a significant portion of presentations to surgical units for management [1]. Quite commonly these cases are initially managed on an acute basis. The initial management of the abscess is for drainage and debridement of the cavity. An abscess cavity caused by a haematological malignancy can be drained, but this does not remove the cause of the abscess as there is residual disease. This case documents a recurrent presentation of peri-anal abscess subsequent to a lymphoma.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old male was transferred from a regional hospital with a non-resolving peri-anal abscess. He initially presented with a trans-sphincteric abscess which was drained in theatre multiple times with progressive sepsis and localised necrosis. Initial cultures and biopsies showed mixed enteric flora and granulation tissue with no evidence of malignancy. He was haemo-dynamically stable, with a mild elevation in neutrophils. His main complaint was pain on sitting and faecal incontinence.

The patient did not have a significant travel history, was not immune-compromised and denied any history of ano-receptive intercourse. Patient's co-morbidities included poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (whilst on insulin and oral hypoglycaemic agents), ischaemic heart disease with percutaneous coronary stent placement within last 2 years and a recent femoral endarterectomy and aorto femoral bypass. He was on dual anti-platelet therapy.

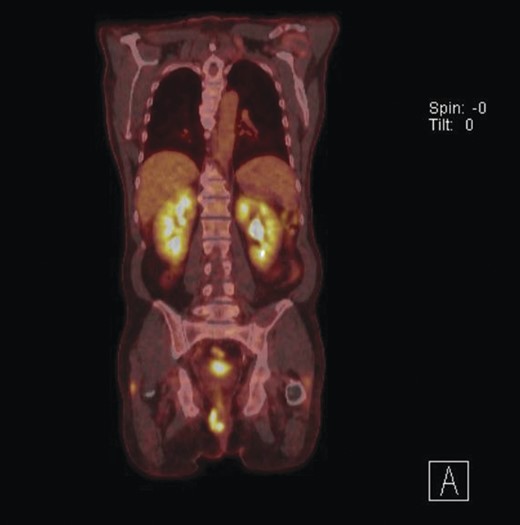

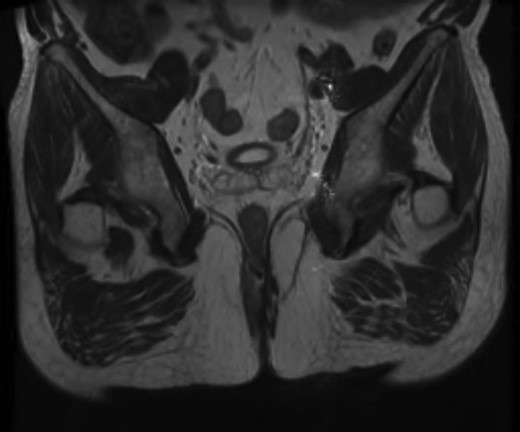

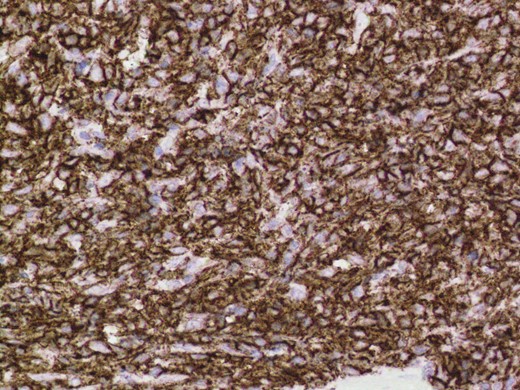

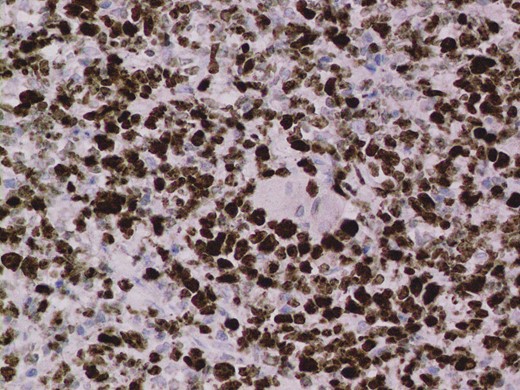

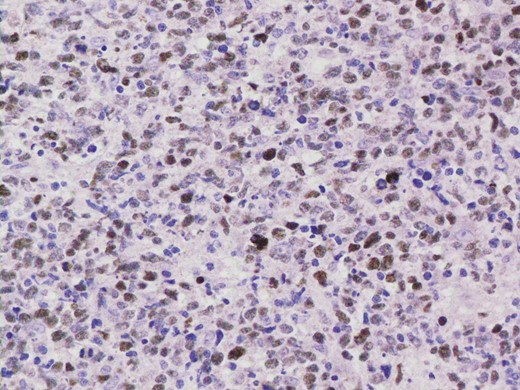

Given the high likelihood of significant vascular disease, a computed tomography (CT) angiogram was done (Fig. 1). Bilateral internal iliac artery stenosis was noted with complete occlusion of the inferior mesenteric artery and right internal iliac artery. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed only localized disease (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his pelvis was significant for a large posterior abscess cavity with soft tissue at the margins with a cavity tracking superiorly along the posterior rectal plane (Fig. 3). The internal sphincter was noted to be necrotic on the last examination (Fig. 4) with a horseshoe cavity and a 10-cm tract running up the posterior aspect of the rectum. Multiple biopsies were taken from the anal margin, abscess cavity and peri-anal tissue, and the histology was consistent with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. There were sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with extensive areas of necrosis. The tumour cells showed strong and diffuse immunohistochemical reactivity for CD20 (Fig. 5), indicating B-cell differentiation. The Ki67 proliferation index was very high (>90%) (Fig. 6) and there was positive in situ hybridisation (ISH) for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (Fig. 7). Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) was performed using a MYC dual colour break apart probe (8q24), and no rearrangement of the MYC gene region was detected. The combined morphological and FISH features were not considered to be those of Burkitt lymphoma.

CT angiogram showing IMA and right internal iliac artery completely occluded.

Magnetic resonance image (MRI) scan showing a large posterior abscess cavity with a cavity tracking posterior to the rectum.

Necrotic internal sphincter and abscess cavity at the posterior aspect of the rectum.

Positive immuno-histochemistry for CD20 indicates a B cell lymphoma.

EBV ISH was positive indicating the presence of EBV encoded RNA in the tumour cells.

Faecal incontinence usually occurs once a significant proportion of the internal sphincter is lost [2]. A defunctioning colostomy was performed and a CHOP-R regimen initiated as definitive therapy.

DISCUSSION

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma accounts for ∼30% of lymphomas. Lymphomas are classified into Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma based on the presence or absence of Reed-Sternberg cells respectively; there are multiple subtypes of each [3]. This patient presented with a DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation, and was EBV-positive.

The aetiology of anorectal abscess formation is wide; ranging from infected anal glands (cryptoglandular theory), inflammatory bowel disease (including Crohns' disease), benign anal conditions (e.g. fistula-in ano), as a complication of surgery, neoplasms and infection [4, 5] Reconstructing the anal canal and the sphincter following chemo-therapy remains a long-term option. This will depend on residual muscle function [1] following treatment and the probability that the patient will remain in remission.

Lymphomas presenting as abscesses have been described in patients with congenital or acquired states of immunodeficiency [6]. Nevertheless, a high degree of suspicion must be present when a non-healing peri-anal abscess is encountered in an non-immune-compromised individuals [7]. Case reports in the literature of anal lymphoma are rare. The importance of good biopsy of tissue and histological surveillance in patients with non-resolving peri-anal conditions is vital.