-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

FD Alves Pereira, H Rai, A rare case of vaginal vault evisceration and its management, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2012, Issue 5, May 2012, Page 6, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2012.5.6

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 66 year old woman presented to A&E with per vagina bleeding and a mass protruding from the vagina. The patient was examined under anaesthesia, which revealed vaginal prolapse with evisceration of approximately 20-30 cm of bowel. The patient had received an abdominal hysterectomy 30 years ago for menorrhagia. In the last decade, the patient had experienced other recurrent episodes of prolapse (cystocoele and retrocoele). Vaginal vault evisceration is a recognised rare complication of hysterectomy and is a gynaecological emergency. This patient’s condition was rapidly recognised and surgically managed. The repair was achieved in two surgeries. Initially, the small bowel was re-inserted into the peritoneal cavity through the vaginal wall defect and the vaginal defect repaired. After sufficient time for healing, a sacrocolpopexy was performed to repair the prolapse.

INRTRODUCTION

The first report of vaginal evisceration was described by Hyernaux in 1864, as disruption of the anterior wall of the proximal vagina, resulting in prolapse of the abdominal contents (1). Since then, there have been just over 120 reports in the literature, although in reality some cases may go unreported (1). Vaginal evisceration is a rare postoperative complication of hysterectomy (regardless of the surgical approach) in women of this age group that carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality and requires rapid surgical intervention. There are different aetiologies depending on the age group – pre-menopausal vs postmenopausal (2). In post-menopausal women vaginal evisceration tends to occur after a hysterectomy. Interestingly, in pre-menopausal women there have been reports of vaginal evisceration following transvaginal ultrasonography (3). The management of vaginal evisceration involves prevention and emergency surgery. There are various surgical approaches (abdominal, vaginal or combined laparoscopic abdominal). The use of each approach depends on the viability of the bowel, whether the defect in the vaginal wall is sufficiently large to replace the bowel back into the peritoneal cavity and on any evidence of foreign bodies in the abdominal cavity.

CASE REPORT

A 66 year old woman presented to A&E with per vagina bleeding, abdominal pain and a mass protruding from the vagina. Prior to this presentation, the patient had suffered for the past decade with cystocoele and retrocoeles. Three decades ago the patient had received an abdominal hysterectomy in order to relieve her symptoms of menorrhagia. Other than arthritis, the patient does not suffer from any other medical condition and was in good health.

On examination the patient seemed well, but her abdomen was distended and tender in the suprapubic, left and right iliac fossa regions. Bowel sounds were absent. On inspection of the genital region there was evidence of vaginal prolapse with a 20-30 cm evisceration of small bowel via a vaginal vault defect. The patient was immediately referred to the gynaecology team.

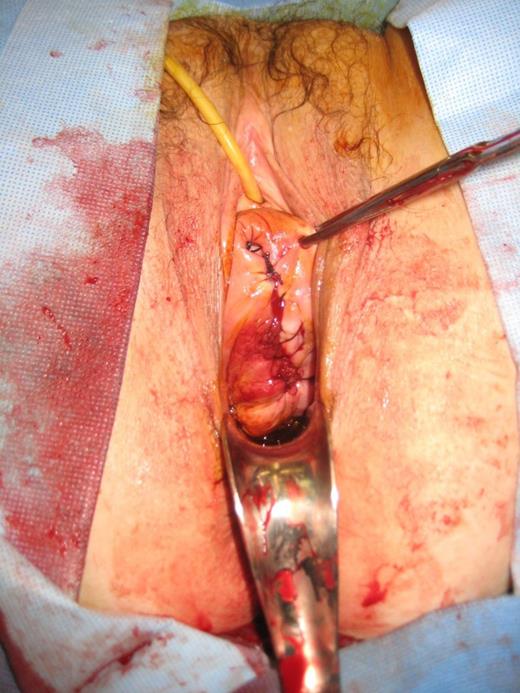

Vaginal evisceration through vaginal vault defect at presentation.

Prior to the emergency operation which aimed to salvage the small bowel, the patient was given antibiotics. The aim of the surgery was to reduce the prolapsed small bowel and re-suture the vaginal wall defect. On inspection by the consultant gynaecologist, the small bowel appeared slightly dusky and an opinion was sought from a consultant general surgeon (who deemed the bowel healthy). The small bowel was replaced through the vaginal wall defect and vaginal wall biopsies taken. The defect in the vaginal wall was closed using vinyl. The patient’s vagina was catheterised and packed. The patient recovered well in the first few days after the operation, though she did have some trouble maintaining the catheter in situ, due to the still uncorrected vaginal prolapse. The catheter was removed on day 5 post-operatively, but the patient had developed a urinary tract infection while catheterised and had to be on i.v. augmentin for this infection. The patient was discharged on day 8, but was to come back 6-8 weeks later for an elective sacrocolpopexy to correct the vaginal wall prolapse.

After complete reduction of small bowel evisceration and correction of vaginal vault defect.

Initially exploratory laparoscopy was performed, the pelvis appeared normal and the consultant decided to perform an abdominal sacrocolpopexy. A Pfannenstial incision was made, small bowel adhesions to right pelvic side wall were noted and divided. The peritoneum between sacrum and posterior vaginal wall was exposed, allowing prolene mesh to be attached to the vaginal wall with prolene and vinyl sutures. The mesh was also sutured to the anterior sacrum. The entire mesh was covered with peritoneum. The rectus sheath was sutured using vinyl and the skin closed with staples (with a drain in situ). Cystoscopy was used to verify the function of the ureters, which revealed both were working well. The patient recovered quickly, there were no post-operative complications and was discharged on day 2 post-operatively.

DISCUSSION

Vaginal evisceration can be a rare complication of hysterectomy which requires urgent surgical attention. This patient had had a hysterctomy many years ago and it is unlikely her vaginal evisceration was a consequence of this surgery directly, but hysterectomy can lead, for example to changes in the vaginal axis. The vagina may come to lie in a more descended position, as it has lost part of its more proximal attachments. This new position combined with factors such as cystocoeles and retrocoeles and their management (for example the insertion of pessaries) may predispose the vagina walls to more “wear and tear” damage. These are risk factors that are likely to have contributed to this lady’s transvaginal evisceration, together with her increasing age susceptibility.

Vaginal evisceration if not recognised quickly can lead to peritonitis and bowel ischaemia. In this lady it quickly recognised and managed well surgically. However, it is important to make emergency doctors aware of these complications and encourage their proper management. When the patient is received by an emergency department and the problem is determined, the emergency doctors must not delay the administration of broad spectrum antibiotics in preparation for taking the patient to theatre and ensure the prolapsed bowel is covered in saline-soaked gauze, as this improves the bowel chances of viability (4).

This case illustrates the need for rapid recognition of vaginal evisceration and its appropriate management in order to avoid morbidity and mortality to the patient.