-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

MA Acosta-Merida, J Marchena-Gomez, M Hemmersbach-Miller, FJ Díaz Formoso, Upper intestinal obstruction due to inverted intraduodenal diverticulum, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 4, April 2011, Page 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.4.1

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Inverted intraduodenal diverticulum is a rare congenital abnormality usually arising near the ampulla of Vater. We describe a case of an inverted duodenal diverticulum in a patient that presented with an upper recurrent intestinal obstruction that required surgery. Recognition of the entity and its anatomic relationships to the ampulla of Vater is essential to the prevention of iatrogenic complications. The inverted intraduodenal diverticulum must be considered in the management of upper intestinal obstruction of unclear origin.

INTRODUCTION

Inverted duodenal diverticulum is an infrequent congenital abnormality that usually is not symptomatic but can become, generally in adult life. If symptomatic, some cases might mimic peptic ulcer disease. This anatomical anomaly has been also related to episodes of upper intestinal bleeding or even acute pancreatitis (1,2). We present a case of an inverted duodenal diverticulum in a patient that presented with an upper intestinal obstruction.

CASE REPORT

A 33-year-old woman with a previous history of fertilization treatments, consulted because of a 2 months vague epigastric and right hypocondric discomfort that was especially more frequent after eating. The patient referred a sensation of fullness/pressure, nausea and abundant alimentary vomiting 2-3 hours after eating and that relieved the pain. This situation had gotten worse over the last days. She was also afraid of eating and had lost 9 Kg of weight during this period. The physical examination was normal except for a mucocutaneous paleness. Initial blood tests revealed moderate hypokalemic, hypochloremic, metabolic alkalosis.

Upper gastrointestinal series showed the presence of an intraluminal duodenal diverticulum of about 8 cm in length and a partially occluded duodenal lumen (figure 1).

Upper gastrointestinal series. Intraluminal duodenal diverticulum, pear-shaped sac, occluding duodenal lumen (arrows).

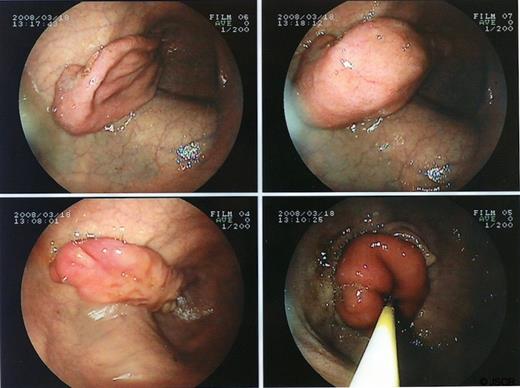

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a inverted intraduodenal diverticulum like a “giant pseudo-polip” that insufflated and deinsufflated spontaneously (figure 2).

Upper intestinal endoscopy showing the inverted intraduodenal diverticulum

The cholangio-MRI and the abdominal CT scan also showed the diverticulum (figure 3), as well as signs of upper intestional malrotation, absence of the pancreatic tail, polysplenia and an hepatic artery that emerged from the superior mesenteric artery.

CT appearance of the intraluminal duodenal diverticulum (arrow).

The patient underwent laparotomy. Abnormal CT findings were confirmed. A cholecistectomy, a transcystic cannulation of Vater’s papilla and a longitudinal duodenotomy on the second portion were performed. An intraluminal formation of 10 cm of length, anchored to three quarters of the duodenal circumference, right next to the papilla and covered by normal mucosa on both sides, was revealed. After circumferencial excision of the inverted intraduodenal diverticulum, an approximation of both mucosal edges was done with reabsorbible stitches, controlling Vater's papilla. The patient was discharged on day 8 after surgery with no complications, except for an autolimited episode of upper intestinal bleeding.

DISCUSSION

Only a low percentage of gastrointestinal diverticula are “inverted” or “intraluminal diverticula”, that is, they have the sac protruding into the duodenal lumen, and less than 150 cases have been previously described in the literature (3). This lesion is usually found in the 2nd portion of the duodenum, very often near Vater’s papilla, as in our patient, covering a variable percentage of the surface of the duodenum.

Its origin has been related to a defect in the development of the duodenum which takes place between the 5th and the 12th week of gestation (1). During this period the complete obliteration of the lumen, the vacuole formation, and the subsequently coalescence of the vacuoles until the complete and definitive permeabilization of the duodenal lumen takes place. Patients with duodenal diverticula are going to present an impaired and incomplete vacuolization (4). Duodenal vacuolization occurs at the same time as the biliary and pancreatic ducts develop and explains the relationship between both congenital defects (5,6).

There is a 40% incidence of coexistant anatomical abnormalities: choledochocele, annular pancreas, double diverticula, intestinal malrotation, imperforate anus, Hirschsprung`s disease, congenital heart diseases, omphalocele, hypoplastic kidneys, bladder exstrophy, situs inversus, Ladd’s bands, portal vein anomalies, polysplenia and Down syndrome (6,7).

The sac grows in isoperistaltic direction into the duodenal lumen (3). The distended diverticulum acts as a large foreign body in the lumen which contributes to produce postprandial fullness and, in some patients, signs of upper intestinal obstruction. When the duodenum is empty, the diverticulum has a tendency to collapse; this explains the asymptomatic periods. Symptoms usually do not appear until the third decade of life. Nevertheless, 20% of patients have had symptoms since childhood. Postprandial fullness, pain, and vomiting are frequently present. Upper intestinal hemorrhage and pancreatitis have also reported in these patients (2). Weight loss might be attributable to alimentary intolerance.

Regarding diagnosis, barium contrast radiology shows images that could be considered patognomonic, with a “bag” of retained barium in the 2nd duodenal portion, occlusive or subocclusive, surrounded by a double radiolucid image with perisacular mucosa duodenal folds. This image has been described as a “windsock blown” into the duodenum (8). The endoscopy can have false negatives because of the device being introduced into the lumen of the diverticulum. Specific findings are “a blind sac lined by normal duodenal mucosa that gives the appearance of a polyp when inverted” (5). In the presented case, the endoscopy was essential for the diagnosis. CT scans and Cholangio-MRI allow physicians to complete the study and to evaluate concomitant congenital abnormalities. (9)

When the patient develops symptoms, conservative management usually has a poor outcome. There have been attempts of endoscopic treatment with variable outcomes (10). Nevertheless, surgery is considered as the best treatment, consisting in an anterior duodenotomy and the excision of the diverticulum (1,6). Procedures like wide Kocher's manouver, or the indentification of Vater's papilla, biliar duct and pancreatic duct are essentials (3). Intraoperatory cholangiography and pancreatography have been recommended. The diverticulum must be extirpated from the mucosa belonging to the “real” duodenum in a circumferential manoeuvre. If it is necessary to reconstruct the papilla or the opening of the pancreatic duct, a silicone stent can be used. (1)

We conclude that inverted duodenal diverticula should be considered in the differential diagnosis of upper intestinal obstruction of unknown cause. Physicians should keep in mind the particular considerations related to Vater's papilla and congenital malformations associated to this condition.