-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

GM Grimsby, CE Wolter, Signet ring adenocarcinoma of a urethral diverticulum, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 4, April 2011, Page 2, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.4.2

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Urethral diverticula are a rare entity. Carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum is a particularly unusual finding with only a little over 200 cases in the reported literature. Adenocarcinoma is the most common carcinoma to occur in a urethral diverticulum. To our knowledge, there are only a handful of cases of signet ring cell adenocarcimona of the urethra and no cases of signet ring adenocarcinoma found in a urethral diverticulum. We present a case report of an incidentally found signet ring cell adenocarcinoma of a female urethral diverticulum.

INTRODUCTION

Carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum is a particularly unusual finding with only a little over 200 cases in the reported literature. We present a case report of an incidentally found signet ring cell adenocarcinoma of a female urethral diverticulum.

CASE REPORT

An 81 year old female complained of suprapubic pain, urethral discharge, urinary frequency, urgency, and stranguria. Past medical history included vulvectomy for vulvar carcinoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in remission after cyclophosphamide, and a 40 pack per year history of tobacco use. Physical examination revealed a firm tender mass at 7 o’clock in the urethra. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed fluid filled lesions on either side of the urethra, see Figure 1. Flexible cystoscopy was negative.

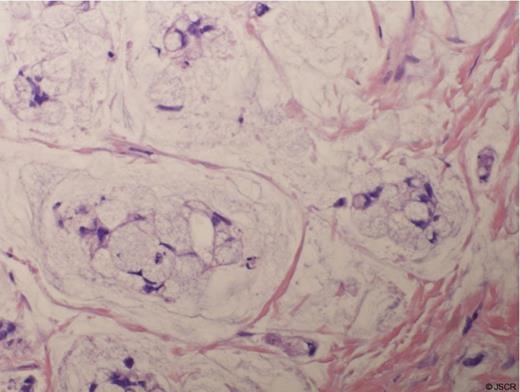

The patient underwent urethral diverticulectomy, during which 2 separate diverticula were noted, one at 5 and one at 7 o’clock. Intra-operative frozen section revealed fibrotic tissue. Final pathology, however, revealed invasive high grade adenocarcinoma involving both diverticula with signet ring cell features and mucin production, see Figure 2.

H&E Stain of the Signet Ring Adenocarcinoma from the Urethral Diverticulum

After a negative colonoscopy and abdominopelvic CT scan, the patient’s disease was felt to be a primary urethral carcinoma and not a metastatic gastrointestinal primary. Hematology agreed with a staging cystourethrectomy and was concerned the carcinoma was a manifestation of her previous cyclophosphamide exposure.

The patient underwent a robotic assisted radical cystectomy, bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection, and ileal conduit urinary diversion. The dissection was taken down as wide as possible, to the farthest reaches of the lateral fornix of the vagina and to the inferior ramus of the pubic bone bilaterally for a wide excision. Final pathology revealed invasive adenocarcinoma, 3.2 cm, surrounding the urethra and invading into the peri-urethral soft tissues, bladder, and vaginal wall with negative margins and lymph nodes. The tumor was composed of well-formed glands containing abundant mucin and signet ring cells.

Five months later the patient developed a tumor recurrence in the vaginal introitus. Wide local excision revealed high grade mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet ring features similar to the patient’s prior lesion. She declined radiotherapy and passed away 1 month later.

DISCUSSION

The etiology of acquired urethral diverticula is recurrent infection of the periurethral glands with obstruction, suburethral abscess formation, and rupture of the glands into the urethral lumen. (1) Diverticula are most often located in the middle third of the urethra with the ostium located posteriolaterally. Congential diverticula may also exist in females and are attributed to congenital anomalies including Skene’s gland cysts or an ectopic ureter draining into a Gartner’s duct cyst. (1)

The prevalence of urethral diverticula is 1-6% of adult women with the majority of patients presenting between the third and seventh decades of life (1). The classic presentation has been described as the “three D’s”: dyuria, dyspareunia, and postvoid dribbling. Other symptoms include recurrent cystitis, pain, vaginal mass or discharge, hematuria, or incontinence. Up to 20% of patients diagnosed with urethral diverticula are asymptomatic (1). During a physical examination, the anterior vaginal wall should be palpated for masses and the urethra may be gently stripped to express purulent material or urine. Cystourethroscopy may be performed in an attempt to visualize the ostium.

Historically, double balloon positive pressure urethrography and voiding cystourethrogram were the diagnostic studies of choice. However, these techniques are invasive and will miss non-communicating diverticula (1). MRI permits noninvasive imaging of diverticula independent of voiding and free of ionizing radiation while allowing for assessment of the extent, structure, and complexity of the diverticulum. With MRI, simply identifying a diverticulum adjacent to the urethra is all that necessary for diagnosis regardless of presence of a diverticular neck (2).

Adenocarcinoma of the female urethra comprises only 10% of all primary urethral malignancies in women and is hypothesized to originate from Skene’s glands, paraurethral ducts, or glandular metaplasia of the urothelium (3). This is in direct contrast to the most common primary carcinoma of the female urethra, squamous cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma can be divided into mucinous and clear cell subtypes (4). The characteristic “signet ring” appearance occurs when abundant mucin accumulates in the cytoplasm of a cell and compresses the nucleus giving the appearance of a “signet ring”.

There was a concern that our patient’s carcinoma was a manifestation of previous cyclophosphamide exposure. Cyclophosphamide is considered a bladder carcinogen and reports of bladder and upper tract malignancies after cyclophosphamide therapy have been described (5).

Carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum is very rare, accounting for 5% of all urethral carcinomas (6). Fewer than 200 cases have been reported in the literature (1). Traditionally, therapy was diverticulectomy alone, which was complicated by high local recurrence rates (6). Treatment has moved towards anterior exenteration with total urethrectomy, similar to the therapy for invasive bladder cancer in a female, to decrease local recurrence. Shalev et al reviewed 79 patients with urethral diverticular carcinoma and compared disease recurrence based on treatment modality. Local recurrence or metastases was seen in 67% of patients treated with diverticulectomy alone, 70% of patients treated with radiation, and 27% of patients treated with anterior exenteration (7).

Multimodal therapy may also be considered, especially for advanced disease. Though no established treatment regimen exists, there are reports in the literature of success with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Seballos et al suggests adjuvant chemotherapy when the diverticular carcinoma involves the bladder neck (8). Awakura et al reported on a patient treated with neoadjuvant radiation, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and leucovorin (9). After treatment, MRI revealed 65% reduction in the size of the tumor and no evidence of disease recurrence was seen 2 years after subsequent resection (9). Davis et al described a patient with disease metastatic to regional lymph nodes who was without evidence of disease 10 months after neoadjuvant platinum-5-FU and radiotherapy, anterior pelvic exenteration, and adjuvant paclitaxel and carboplatin (10).

We describe a unique signet ring adenocarcinoma in a urethral diverticulum. Urethral diverticula are rare but it is important to keep the diagnosis in mind, especially in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and a palpable urethral mass, as one never knows what they may find in the diverticula as was the case with our patient. Pelvic MRI is the diagnostic modality of choice. Unfortunately, as many cases of carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum are diagnosed at an advanced stage, initial treatment should be aggressive, in the form of anterior exteneration and urethrectomy with consideration of radiation and chemotherapy.