-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Modupe Oyewumi, Kevin Higgins, Danny Enepekides, Simon Rapha, Hypertension and a Large pulsatile neck mass: A Case of Malignant Glomus Vagale Tumour, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2010, Issue 6, August 2010, Page 2, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2010.6.2

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This teaching case report represents an unusual example of a neck mass in a previously healthy individual. The presence of a new neck mass is a relatively common head and neck problem and requires a full work up including a complete history and physical examination. With respect to our patient, thorough history taking, physical examinations and specific investigations led to the diagnosis of a malignant and functionally active paraganglioma.

Vagal paraganglioma themselves are rare tumours and account for only 5-25% of all paragangliomas in the head and neck region. The presence of a malignant, functionally active, catecholamine-secreting paraganglioma is even rarer and accounts for only 1-3% of all reported glomus vagale tumours.

This case report illustrates the need to carefully monitor all neck masses for changes in size, for any distortion to surrounding structures, and their given function.

INTRODUCTION

Vagal paragangliomas are rare tumours that are estimated to account for 5-25% of all paragangliomas of the head and neck region (1,2). They can develop anywhere along the course of the vagus nerve and their clinical presentation depends on where it is located in the parapharyngeal space. The most common symptoms are neck masses, dysphonia, dysphagia, fullness of the pharynx, pain, and coughing. The presence of a functionally active paraganglioma that secretes catecholamies is only found in 1-3% of all reported cases (3). These patients usually present with adrenergic symptoms similar to a pheochromocytoma. Malignant paragangliomas are also rare and are found in 10-19% of cases (4). Malignancy is diagnosed via the presence of metastases in lymph nodes.

In this case report, we describe a man presenting with the most common symptoms of a progressively growing neck mass and dysphonia, and an eventual diagnosis of a malignant, functionally active paraganglioma.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 61- year- old right-handed male presented to his family physician with a right neck mass and a worsening hoarse voice (dysphonia). The neck mass had been present for the past few years, but had noticeably increased in size during the past 2 months. It was during this period of accelerated growth that his dysphonia began. When he presented to his family physician, his dysphonia had worsened when compared to its original onset and was resulting in voice fatigue and pitch breaks. He also complained of associated constitutional symptoms of dizziness and malaise. His past medical history was significant for labile hypertension, coronary artery disease, with a myocardial infarction and subsequent stent insertion, diabetes mellitus type 2, and hypercholesteremia.

His family physician ordered a CT neck and referred him to our hospital for an Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery consult. During his initial assessment, his physical exam confirmed the presence of a pulsatile neck mass involving levels 2, 3, and 4 with extension into the tail of the parotid. The cephalad extent of the mass was located above the angle of the mandible.

At the completion of the examination, a tentative diagnosis of a right glomus vagale paraganglioma with right vocal cord paralysis was rendered. Further lab and imaging investigations were required to confirm the diagnosis and determine the presence of any coincidental or metastatic disease. A 24h-urine test was performed and it revealed elevated norepinephrine (3011 nmol/d [N: <600nmol/d), creatinine (107 ummol/L [N: 44-106]), and a norepinephrine/creatinine ratio (292.3 umol/mmol [N <70 umol/mmol]), thus confirming biochemical catecholamine activity, suggesting a presumptive diagnosis of a biochemically active glomus vagale.

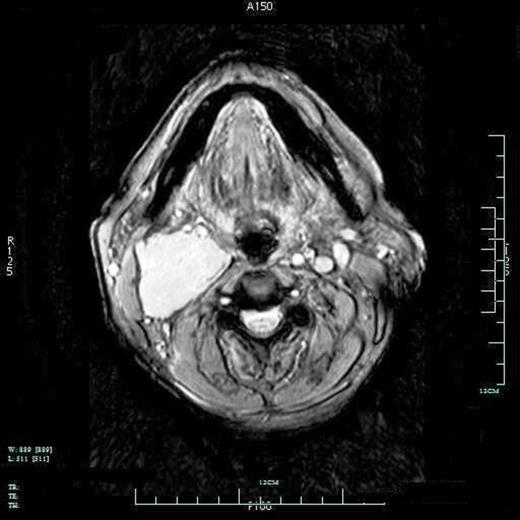

CT angiogram (Figure 1) confirmed the palpable neck mass to be a glomus vagale. A 4cm x 4cm x 8.5cm vascular lesion was found posterior to the carotid sheath with anterior displacement of carotid bifurcation and the internal carotid artery. The vascular lesion extended from the level of the proximal carotid bifurcation to the skull base. There was no evidence of superior extension. The right jugular bulb remained intact and hypoplastic when compared to the left jugular bulb. There was evidence of effacement of the oropharynx by the mass. Inner ear structures were clear and brain parenchyma and ventricles were unremarkable. Lung apices and bone were also unremarkable for metastases. No contralateral cervical lesions were present. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was unremarkable. No adrenal or retroperitoneal masses or enlarged lymph nodes were identified. Results confirmed the lack of a coincidental pheochromocytoma.

CT angiography of a 4 x 4 x 8.5cm right glomus vagale. Mass is located posterior to the carotid sheath with anterior displacement of carotid bifurcation and the internal carotid artery.

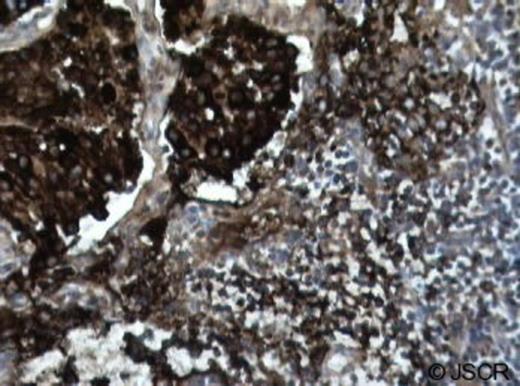

Prior to surgery, the patient had an interventional radiology tumour embolization. This was done to devascularize the tumour as thoroughly and safely as possible in order to limit the amount of surgical blood loss. The next day, the patient underwent a right neck dissection, parotidectomy and right glomus vagale tumour resection and right injection laryngoplasty. There were no peri-operative complications. The right vagus nerve, glomus vagale tumour, and right thyroid were sent to pathology. The dissected tumour mass can be seen in Figure 2. Surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of the neck mass as a vagale paraganglioma. The pathology report also revealed the presence of metastatic tumour in a positive chromogranin-stained lymph node, thus fulfilling the criteria for malignancy.

Chromogranin-stain of the dissected lymph node. Lymph node stained positive for chromogranin, confirming the presence of metastatic disease (dark brown/black cells).

The patient was discharged 15 days post-surgery. A follow up appointment was booked at the otolaryngology clinic for a few weeks post-hospital discharge, with radiation oncology consultation.

CONCLUSION

A new neck mass is a relatively common head and neck problem. For patients presenting with adrenergic-type symptoms, a 24h urine test can be done to detect the presence of a biologically active tumour. Imaging studies can help to confirm the presence of the mass, its extent, as well as to help narrow the possible diagnoses. Neck masses should be carefully monitored for changes in size and for any distortions to surrounding structures and their given function.

The main methods of treatment for a malignant paragangliomas include radiotherapy or surgery. Radiotherapy is associated with a lower incidence of complications and morbidity, but only provides partial local control of paragangliomas. Surgery is the only method that ensures complete removal of the paraganglioma. Therefore, surgery is considered the treatment of choice for both benign and malignant vagal tumours. Embolization is performed pre-operatively to safely and thoroughly devascularize the paraganglioma. For patients with functionally active vagal paragangliomas, symptomatic relief of the associated cardiovascular symptoms is sometimes necessary. Alpha and beta blockades are used to accomplish this goal. Careful follow-up post treatment is necessary to monitor the patient's well being and status.