-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kevin J Fuentes-Calvo, Francisco E Alvarez-Bautista, Oscar Santes, Luis F Arias-Ruíz, Noel Salgado-Nesme, Primary colonic lymphoma: clinical dilemmas in diagnosis and treatment strategy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf744, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf744

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Primary colonic lymphomas are uncommon, comprising ˂1% of colorectal cancers and up to 20% of gastrointestinal lymphomas. The most frequent subtype is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), typically presenting with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain or obstruction. Diagnosis requires histopathologic and immunophenotypic confirmation. While treatment is primarily systemic with immunochemotherapy, surgery may be necessary in cases of complications or for diagnosis. We report a case of a 75-year-old woman presenting with right-sided colonic obstruction. Imaging revealed a mass in the ascending colon; an extended right hemicolectomy with ileostomy was performed. Histopathology confirmed DLBCL with post-germinal center phenotype. The patient recovered uneventfully and was referred for outpatient oncology care. This case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic relevance of surgical intervention in selected presentations of primary colonic lymphoma.

Introduction

Primary colonic lymphomas are rare malignancies, comprising ˂1% of colorectal cancers. Most are B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) being the most common subtype. Diagnosis is often challenging due to nonspecific symptoms, and management typically relies on systemic immunochemotherapy. The surgery retains an important role in selected cases, particularly those with complications or localized disease. This report discusses a surgically treated case, underscoring the diagnostic challenges and the evolving role of surgical intervention in this context.

Case report

A 75-year-old female with a medical history of systemic arterial hypertension and hypothyroidism under treatment presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain and distension. She denied hematochezia, changes in bowel habits, or unintentional weight loss.

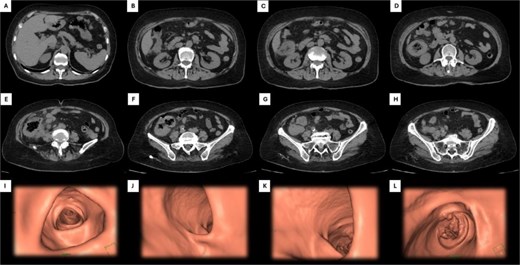

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed concentric and diffuse thickening of the ascending colon, up to 15 mm in diameter, extending from the ileocecal valve to the hepatic flexure. Submucosal enhancement with pericolic fat stranding, mesenteric lymphadenopathy, and a right inguinal mesenteric nodule were observed, along with pulmonary nodules up to 23 mm in the left lung base (Fig. 1).

Abdominal CT and 3D colonoscopy. Images A–H depict the descending sequence of axial CT slices, with the white arrow indicating the lesion at the colonic level. Images I–L correspond to selected views from a virtual colonoscopy: Image I shows the transverse colon, J the hepatic flexure, K the ascending colon and cecum, and L highlights the lesion located in the cecum.

On physical examination, the patient exhibited tenderness in the right hemiabdomen, increased abdominal girth, and a palpable mass in the right iliac fossa. A diagnosis of right colonic obstruction was established, prompting an exploratory laparotomy. An extended right hemicolectomy with protective ileostomy was performed.

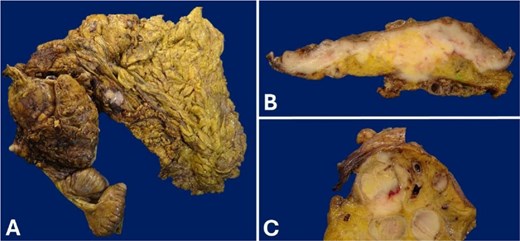

The macroscopic examination report a tumor measured 10.6 × 10.0 cm and ulcerated the colonic mucosa. Upon serial section, the tumor was white to pink, fleshy too soft with diffuse borders, and “fish-flesh” appearance. It infiltrated the full thickness of the colonic wall, as well as the vermiform appendix. Multiple affected lymph nodes were found in the pericolonic fat and omentum (Fig. 2).

Gross appearance of the cecum wall. (A) Product of right hemicolectomy. (B) The tumor that infiltrates the full thickness of the cecal wall. The lesion involves the mucosa, which is ulcerated. (C) Conglomerate of lymph nodes.

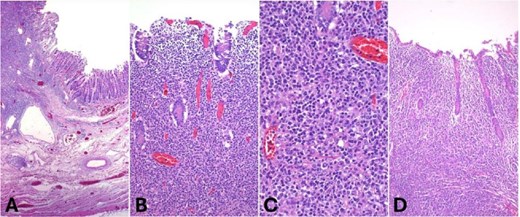

Histologically, the tumor infiltrated the full thickness of the intestinal wall, including the vermiform appendix, and involved multiple regional lymph nodes. It displayed a diffuse growth pattern and caused ulceration of the colonic mucosa. The neoplastic population consisted of large atypical lymphocytes with irregular nuclei, granular chromatin, and scant cytoplasm (Fig. 3).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. (A) Low-power view showing diffuse infiltration of the intestinal wall by a dense lymphoid neoplasm (40×, H&E). (B) The tumor extensively involves the mucosa (100×, H&E). (C) High power view showing large atypical lymphoid cells with irregular round nuclei and dispersed chromatin (400×, H&E). (D) Appendiceal wall infiltrated by the neoplasm.

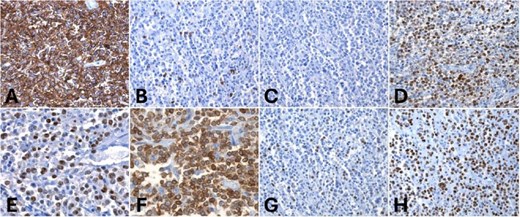

Immunohistochemically, the lymphoid cells were positive for CD20 and negative for CD5, consistent with B-cell lineage. The tumor cells were also CD10-negative, BCL6-positive, and MUM1 positive, indicating a post-germinal center phenotype. BCL2 expression was diffuse, and c-MYC was positive in ⁓10% of the tumor cells. The proliferation index (Ki-67) was 70% (Fig. 4). Final diagnosis was DLBCL of the large intestine, with post-germinal center origin, based on immunophenotypic profile (Fig. 3). The patient experienced an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged for follow-up and immunotherapy management in the outpatient medical oncology clinic.

Immunohistochemistry. (A) Diffuse and strong CD20 positivity in tumor cells, (B, C) negative CD5 and CD10 in neoplastic cells but positive MUM1 and BCL6 for tumor cells (D, E). Strong BCL2 and c-MYC positivity in 10% of tumor cells (F, G). (H) Ki67 proliferation index: 70%.

Discussion

Primary colonic lymphomas are rare lymphoid neoplasms that originate in the colonic wall without initial evidence of systemic or distant nodal involvement. They account for ˂1% of colorectal malignancies and ⁓10%–20% of primary gastrointestinal lymphomas [1, 2]. Dawson’s criteria define them by the absence of peripheral or mediastinal lymphadenopathy, uninvolved bone marrow, liver, and spleen, and confinement of the tumor to the gastrointestinal tract at diagnosis [3].

The vast majority are non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas, with DLBCL being the most common subtype, representing 40%–50% of cases [1, 4]. Other subtypes include mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (10%–20%), follicular lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, the latter often associated with multiple lymphomatous polyposis. Primary Tcell lymphomas of the colon are extremely rare (<5%) and generally associated with worse prognosis [2].

Epidemiologically, these lymphomas occur more frequently in men (⁓2:1) and are typically diagnosed between the ages of 55 and 60 [5]. Population-based data show a rising incidence in the United States, increasing from 1.4 cases per million in 1973 to 3.5 cases per million in 2014 (P < 0.001), particularly among individuals over 60 years of age [1]. Predisposing factors include immunosuppressive conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus infection, organ transplantation, autoimmune diseases, and a history of other lymphoid neoplasms. The ileocecal region is the most common site, likely due to its high lymphoid tissue content [2, 5].

Clinically, the most frequent symptom is diffuse abdominal pain, followed by unintentional weight loss and changes in bowel habits [2, 5]. Less commonly, patients may present with lower gastrointestinal bleeding, systemic B symptoms, or acute complications such as obstruction, perforation, or intussusception. A significant proportion are diagnosed incidentally during screening colonoscopies. Endoscopic findings range from polypoid lesions to ulcerations or diffuse mucosal infiltration [2]. Definitive diagnosis requires endoscopic biopsy with histopathologic and immunophenotypic evaluation, complemented by imaging for staging [CT or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT] and classification according to the Ann Arbor/Lugano system.

Treatment is primarily based on systemic chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy, with R-CHOP remaining the standard regimen for aggressive B-cell lymphomas [2, 5]. In selected cases of localized and indolent lymphomas—such as MALT or follicular lymphoma—initial observation or monotherapy with rituximab may be appropriate, although most patients eventually require systemic treatment [2].

The role of surgery has evolved over time. Previously considered routine, surgical resection is now used more selectively. A SEER database analysis of 3537 patients showed that surgery combined with chemotherapy reduced overall mortality by 17% (HR = 0.83; 95% CI: 0.75–0.93; P = 0.0009) [4]. However, other studies have not shown clear benefit in advanced disease, reserving surgery for complicated cases or resectable tumors in early stages [2, 5].

Prognosis has improved significantly in recent decades, with current 5-year survival rates ranging from 60% to 80%, depending on stage and histological subtype [1, 5]. Poor prognostic factors include advanced stage, T-cell histology, older age, and presence of B symptoms, while localized disease, B-cell phenotype, and combined surgical and systemic therapy are associated with better outcomes [2, 4].

Conclusion

Primary colonic lymphoma is an uncommon entity that requires a high index of suspicion for timely diagnosis. Optimal management combines systemic therapy with surgical intervention in selected cases, achieving significantly improved survival rates compared to past decades. The rarity of the disease highlights the importance of referral to specialized centers and multicenter collaboration to generate high-quality evidence and improve treatment strategies.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.