-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dison Feyang Limbu, Ashish Kiran Shrestha, Jann Yee Colledge, Gallbladder agenesis – a unique condition with common symptoms, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf729, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf729

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Agenesis of the gallbladder is a rare abnormality with an incidence of 0.01%–0.06% and affects more women than men. Many patients can present with abdominal pain, particularly biliary colic. A woman presented with symptoms and signs of biliary colic-type pain. There was no history of cholecystectomy surgery. All her routine bloods, including inflammatory markers, liver function test, and amylase, were within normal limits. A combination of transabdominal ultrasound, computerised tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scans concluded gallbladder agenesis without extrahepatic biliary atresia. Currently, she is being managed conservatively with analgesia and antispasmodics. Diagnosis begins by first excluding common pathologies. MRCP is the recommended investigation to diagnose gallbladder agenesis. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction can cause biliary colic pain and this is suggested to be the mechanism of pain seen with gallbladder agenesis. Antispasmodic medication with simple analgesia is effective for management of symptoms.

Introduction

Agenesis of the gallbladder is when a person is born without a gallbladder. This is a rare abnormality with an incidence of 0.01%–0.06% [1]. Approximately 50% of patients can present with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, which can imitate biliary colic pain; however, many can remain asymptomatic [2]. Women are affected more than men, with a likelihood ratio of 3:1, and typically affects patients in their 20s–30s [3]. We present a rare case of gallbladder agenesis.

Case report

A woman in her 50s presented with a 3-day history of sudden-onset, sharp, intermittent right upper quadrant pain with radiation to the right shoulder. The pain was exacerbated on eating, particularly fatty foods. On examination, she was tender, on both superficial and deep palpation, over the right upper quadrant with a positive Murphy’s sign. She was afebrile and denied associated symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting. She had presented with similar symptoms five days prior, which were managed with analgesia, and she was subsequently discharged.

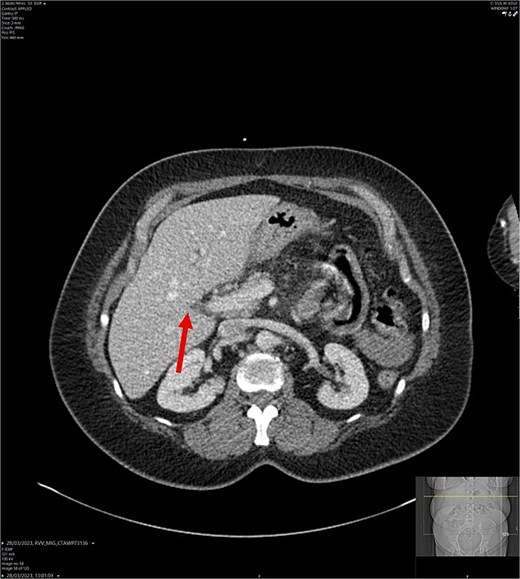

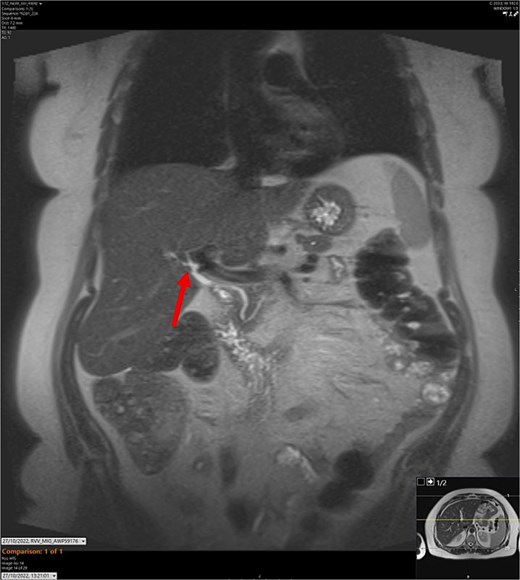

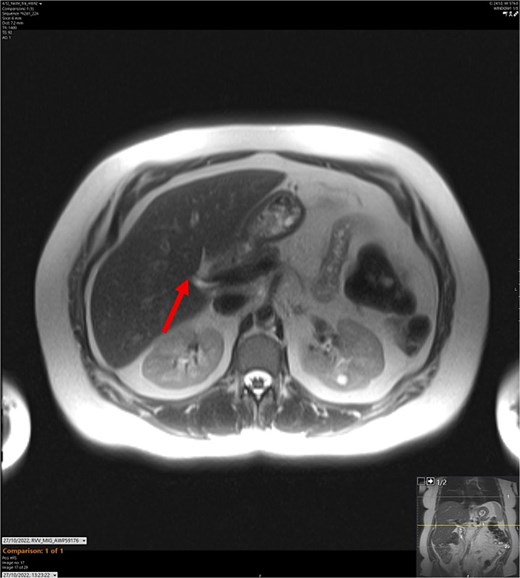

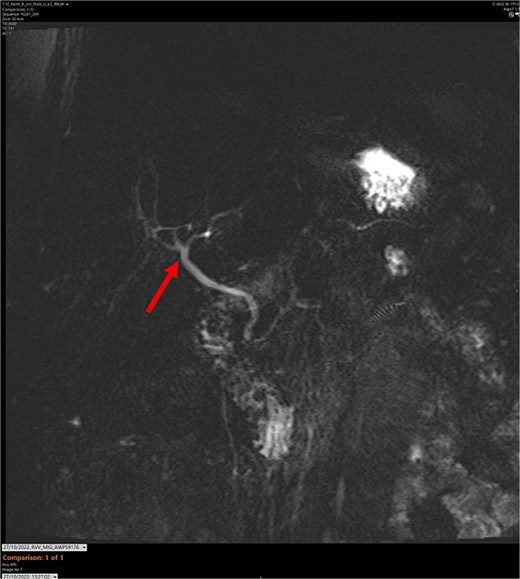

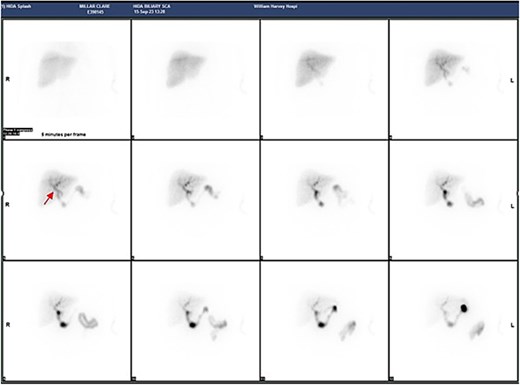

On admission, the patient’s blood tests showed normal inflammatory markers, liver function markers, and amylase (Table 1). The patient underwent an abdominal ultrasound scan, which did not visualize gallstones or the gallbladder. A computerised tomography (CT) abdomen-pelvis scan was done, and the gallbladder could not be visualized (Figs 1 and 2). Further investigations, which include a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan, confirmed a gallbladder bud with an intact biliary tree (Figs 3–6). The patient denied a history of a cholecystectomy. She was diagnosed with gallbladder agenesis.

| Blood test . | Value . | Reference range . |

|---|---|---|

| C-Reactive Protein | 1 mg/L | <5 mg/L |

| White Cell Count | 9.6 × 109/L | 4.0–11.0 × 109/L |

| Amylase | 34 U/L | 28–100 U/L |

| Total Bilirubin | 8 μmol/L | <21 μmol/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 42 U/L | 30–130 U/L |

| Alanine Transaminase | 25 U/L | <34 U/L |

| Albumin | 44 g/L | 35–50 g/L |

| Blood test . | Value . | Reference range . |

|---|---|---|

| C-Reactive Protein | 1 mg/L | <5 mg/L |

| White Cell Count | 9.6 × 109/L | 4.0–11.0 × 109/L |

| Amylase | 34 U/L | 28–100 U/L |

| Total Bilirubin | 8 μmol/L | <21 μmol/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 42 U/L | 30–130 U/L |

| Alanine Transaminase | 25 U/L | <34 U/L |

| Albumin | 44 g/L | 35–50 g/L |

| Blood test . | Value . | Reference range . |

|---|---|---|

| C-Reactive Protein | 1 mg/L | <5 mg/L |

| White Cell Count | 9.6 × 109/L | 4.0–11.0 × 109/L |

| Amylase | 34 U/L | 28–100 U/L |

| Total Bilirubin | 8 μmol/L | <21 μmol/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 42 U/L | 30–130 U/L |

| Alanine Transaminase | 25 U/L | <34 U/L |

| Albumin | 44 g/L | 35–50 g/L |

| Blood test . | Value . | Reference range . |

|---|---|---|

| C-Reactive Protein | 1 mg/L | <5 mg/L |

| White Cell Count | 9.6 × 109/L | 4.0–11.0 × 109/L |

| Amylase | 34 U/L | 28–100 U/L |

| Total Bilirubin | 8 μmol/L | <21 μmol/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 42 U/L | 30–130 U/L |

| Alanine Transaminase | 25 U/L | <34 U/L |

| Albumin | 44 g/L | 35–50 g/L |

CT abdomen-pelvis scan in coronal view. The arrow points to where we expect the gallbladder to be seen, but it cannot be visualized on the scan.

CT abdomen-pelvis scan in axial view. The arrow points to where we expect the gallbladder to be seen, but it cannot be visualized on the scan.

T2-weighted MRCP scan in coronal view. The arrow points to where we expect the gallbladder to be seen, but it cannot be visualized on the scan.

T2-weighted MRCP scan in axial view. The arrow points to where we expect the gallbladder to be seen, but it cannot be visualized on the scan.

MR maximum intensity projection scan. The arrow points to the largely intact biliary tree. The cystic duct cannot be seen branching from the common bile duct.

Series of HIDA scans. The arrow points to likely a gallbladder bud.

The patient was managed with simple analgesia, including oral morphine pro re nata, and oral hyoscine butylbromide.

After follow-up a year later, she is being managed conservatively with simple analgesia and antispasmodics, which effectively control her pain. She has been referred to a tertiary centre for endoscopic ultrasound and Sphincter of Oddi (SOD) manometry to identify the cause behind her symptoms, such as SOD dysfunction.

Discussion

It is interesting to see how such a rare condition presents with a typical biliary symptom. However, diagnosis begins by ruling out common pathologies. The most common causes of right upper quadrant pain are biliary colic, cholecystitis, and choledocholithiasis [4]. However, the patient’s unremarkable inflammatory markers and LFTs contradict the diagnoses. The absence of gallbladder and gallstones in the biliary tree was confirmed on ultrasound and MRCP, which ruled out biliary colic, cholecystitis, and choledocholithiasis. Normal amylase levels, in addition to normal inflammatory markers, indicated that acute pancreatitis was unlikely. Also, the CT scan did not show any signs of acute pancreatitis, such as decreased pancreatic enhancement, peripancreatic fat stranding, or peripancreatic fluid collections.

Gallbladder agenesis has been well documented in the form of case reports, although how it causes biliary colic-like pain is poorly understood; SOD dysfunction is a suggested mechanism [5, 6]. In SOD dysfunction, the flow of bile is interrupted by an acalculous obstruction. Gallbladder agenesis and cholecystectomy are both risk factors for SOD dysfunction. The pathogenesis of SOD dysfunction includes scarring from biliary stones or crystals, increased pressure from a thickened sphincter present at birth, or SOD smooth muscle spasms caused by neuronal or hormone stimuli [7]. This can cause backflow of bile, which increases the pressure in the SOD and causes biliary colic-like pain, akin to pathophysiology in post-cholecystectomy syndrome [6, 7]. Additionally, it has been reported that antispasmodics can alleviate the pain [5, 8], which supports this theory.

MRCP has been shown to be an effective investigation to diagnose gallbladder agenesis [2, 5]. However, due to the rarity of gallbladder agenesis, common pathologies must be first excluded. Although there is literature advising laparoscopic exploration, an invasive procedure is argued to be unnecessary due to the high sensitivity of MRCP [2, 6, 9]. As SOD dysfunction is suggested to cause biliary colic pain, SOD manometry can be used to diagnose this [10].

There are no guidelines for treating gallbladder agenesis. Pain can be managed with a combination of hyoscine butyl-bromide and simple analgesics [5–9]. The use of nifedipine in patients with SOD has also been shown to be effective. A study by Khuroo et al. [11], showed that taking nifedipine led to fewer pain episodes, fewer emergency visits, and used less pain medication compared to a placebo.

If conservative management is ineffective, sphincterotomy can be considered depending on the Milwaukee classification of SOD (Type I, II, and III). Type I SOD is characterized by both abnormal biochemical markers and dilated biliary or pancreatic ducts seen on imaging. Type II is characterized by abnormal biochemistry or imaging. Type III SOD has neither. Sphincterotomy is advised for Type I and II SOD. However, it is not advised in Type III due to ineffectiveness and risk of post-sphincterotomy pancreatitis [7, 10].

In conclusion, gallbladder agenesis can present similarly to biliary colic, cholecystitis, and choledocholithiasis. The pathophysiology behind this is suggested to be SOD dysfunction. MRCP is the diagnostic tool of choice. It is recommended to manage gallbladder agenesis conservatively; symptom control with hyoscine butyl-bromide, nifedipine, and simple analgesia is recommended. If conservative management is ineffective, sphincterotomy can be considered depending on the Milwaukee classification of SOD.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References

Khuroo MS, Zargar SA, Yattoo GN. Efficacy of nifedipine therapy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross over trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1992;33:477–85.