-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Zhengchao Xu, Christian Pappas, Mina Sarofim, Con Manganas, Ruwanthi Wijayawardana, David Morris, Bilothorax following peritoneal cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf681, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf681

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bilothorax is a rare and under-recognized complication of hepatobiliary interventions, especially cytoreductive surgeries and is associated with increased length of hospitalization, morbidity and mortality. There are ˂100 reported cases in the literature, and due to its rarity, no standardized diagnostic tests or treatment guidelines are currently available. We present a 58-year-old otherwise healthy woman with a history of recurrent ovarian cancer who underwent cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with curative intent. Her postoperative course was complicated by delayed abdominal bile leak, followed by progressive respiratory decline which failed initial conservative treatments. She underwent drainage and frank bile was obtained. The patient ultimately responded to broad-spectrum antibiotics and the placement of dual intercostal-abdominal drainage catheters. This article highlights the diagnostic challenges of bilothorax, a rare condition with non-specific and varied presentations, particularly in the absence of thoracic trauma.

Background

Bilious effusion (Bilothorax or Cholethorax) is a rare cause of exudative pleural effusion of extra-vascular origin [1, 2]. The exact incidence is unclear and is typically associated with surgical manipulation of the hepatobiliary system, biliary obstruction, infection, or abdominal trauma [1, 2, 3]. Diagnosis is often delayed and relies on a high clinical index of suspicion. We present a unique case of bilothorax following cytoreductive surgery, which to our knowledge is the first such case within the literature.

This article highlights a rare thoracic complication in hepatobiliary surgery, discussing the diagnostic challenges and cognitive processes involved. It emphasizes the need for high suspicion and personalized treatment strategies to ensure successful outcomes.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old female was referred to our facility for cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer. She had no significant cardio-respiratory comorbidities. Intraoperatively, invasive tumor deposits were found involving the hepatic artery, portal vein, and right hemidiaphragm. Due to her young age and excellent functional status, a multidisciplinary team decided to proceed with right diaphragm peritoneal stripping, partial non-anatomical liver resection, and hilar lymph node dissection for complete cytoreduction with curative intent. The non-anatomical liver resection involved a front-to-back hilar dissection, with tumor resected off both the hepatic artery and portal vein. A cholecystectomy was performed for tumor involvement of the gallbladder, with cystic duct and artery ligated using Ligaclips and suture ties. The right hemidiaphragm was stripped using a combination of diathermy and ball cautery. Tumor was dissected off the inferior vena cava, although a plaque of tumor remained adherent to its anterior wall. The liver was fully mobilized, and Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator dissection was used to carefully separate tumor tissue from the hepatic hilum. There was no evidence of intraoperative bile leak or immediate complications post-operatively.

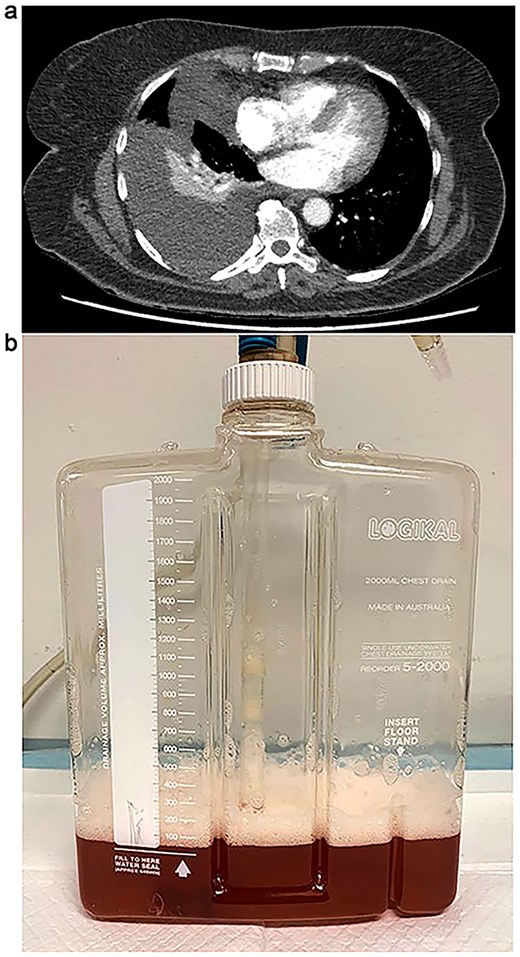

On postoperative day 10, a bile leak was suspected due to high-volume hepatic drain output of dark brown fluid. However, an initial computed tomography (CT) cholangiogram failed to identify a source of the leak. By day 20, the patient developed worsening exertional dyspnoea and orthopnoea. A CT pulmonary angiogram ruled out pulmonary embolism but revealed a right-sided pleural effusion with compressive atelectasis in the right lower lobe (Fig. 1a). She was treated with intravenous diuretics, physiotherapy, and incentive spirometry.

(a) CT chest demonstrating progressive large right-sided pleural effusion with new loculation and compressive right lower lobe collapse. (b) Bilious pleural fluid with froth following ultrasound guided intercostal pigtail catheter insertion.

Due to further respiratory deterioration, repeat imaging was performed and showed an increase in the right pleural effusion with new loculation (Fig. 1a). An ultrasound-guided pigtail drain was inserted, and analysis of the turbid bilious pleural fluid confirmed bilothorax with an elevated pleural fluid to serum (PF/S) bilirubin ratio of 7.6 (Fig. 1b). There were no malignant cells or microorganisms in the fluid. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started for potential respiratory and intra-abdominal sepsis. A follow-up chest radiograph 4 days after thoracentesis showed near-complete resolution of the effusion. The patient was discharged on day 30 postoperatively and remained well, with no symptom recurrence at her 1-month follow-up.

Discussion

Bilothorax is a rare condition characterized by abnormal bile accumulation in the pleural space, and to date has fewer than 100 reported cases in the literature, with its exact incidence still unclear [1, 2]. It typically occurs in the context of abdominal trauma, iatrogenic hepatobiliary manipulation, biliary obstruction, malignancy, or infection [3, 4, 5].

Bile can enter the pleural space through various pathways, including passive diffusion via diaphragmatic pores and lymphatics due to negative intrathoracic pressure, or active passage through natural or iatrogenic connections, such as diaphragmatic defects or biliopleural fistulae [1, 2, 5]. Most bilothoraces occur on the right side because of the anatomical location of hepatobiliary structures [2]. Left-sided or bilateral cases are exceedingly rare and typically associated with conditions like abdominal spillage, pancreatitis, or malignancy [3, 5]. In this case, bilothorax was caused by a combination of pre-existing malignancy, extensive hepatobiliary dissection, and diaphragm stripping.

Diagnosis of bilothorax requires a high clinical suspicion, combined with pleural fluid analysis and radiological evaluation. The color of the effusion, which can range from dark yellow to green or brown, is not a reliable indicator of bile [1]. A PF/S bilirubin ratio greater than 1.0 is pathognomonic for bilothorax [1, 2]. However, in a systematic review of 52 bilothorax cases, this ratio was only reported in 27% of cases, with a mean of 8.4, consistent with another review showing a mean of 4.15 [1, 2].

Due to its rarity, no standardized treatment guidelines exist for bilothorax. Treatment strategies emphasize source control and preventing complications like chronic biliopleural fistulae and empyema [4, 5]. Conservative management involves broad-spectrum antibiotics and early therapeutic drainage. In cases of complex non-resolving effusion or empyema, Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy or stents may be used after liver resection to reduce pressure [5]. Prevention of bilothorax is multi-pronged and relies on anticipating the risk of bile leak and pleural translocation through careful surgical technique, intraoperative leak testing, inspection and repair, early drain placement, and vigilant postoperative monitoring. The take home message is pleural effusion in a postoperative patient with a known diaphragmatic or hepatic procedure should prompt pleural fluid aspiration and analysis, including bilirubin testing, even if the effusion appears reactive or small.

Conclusion

Bilothorax is a rare and often underdiagnosed complication of hepatobiliary surgery. Diagnosis relies on the presence of risk factors, an elevated PF/S bilirubin ratio above 1.0, and radiological evidence of bile accumulation. Early management focuses on source control with broad-spectrum antibiotics and drainage, with surgery considered for complications like fistulas, empyema, or worsening systemic conditions.

This article highlights the diagnostic challenges of bilothorax, a condition with non-specific and varied presentations, particularly in the absence of thoracic trauma. Detection is further complicated by negative imaging and limited non-invasive diagnostic options, which may not be available in remote or after-hours settings. The complexity of cases often requires a multidisciplinary approach, and the article stresses the importance of recognizing clinical pitfalls and cognitive biases, as well as re-evaluating initial diagnoses to enhance diagnostic accuracy and improve patient outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None declared.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images.