-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Muath Alasheikh, Muath AlRashed, Abdullah S Al-Darwish, Hamad S AlSaeed, Mohamed S Essa, Trichobezoar-induced gastric outlet obstruction in a 17-year-old girl: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf690, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf690

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is an uncommon, yet potentially severe, condition arising from multiple causes, including ingesting foreign bodies. The formation of plastic bezoars or trichobezoars due to swallowing indigestible materials remains a rare cause, especially among children exhibiting pica behavior (Vaughan et al. The Rapunzel syndrome: an unusual complication of intestinal bezoar. Surgery 1968;63:339–43). We present a 17-year-old female with a known history of pica who presented with symptoms of abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, and inability to tolerate oral intake. Examination revealed a palpable mass in the abdomen. Imaging and endoscopic evaluations revealed a large trichobezoar occupying the stomach and extending into the first part of the duodenum, obstructing the gastric outlet. Endoscopic attempts at removal were unsuccessful due to the bezoar’s size and extension, necessitating an open surgical procedure. The patient experienced an uneventful recovery and was referred for psychiatric follow-up to manage her pica and prevent recurrence. This case emphasizes the critical need for timely identification and a comprehensive treatment approach. It involves both surgical removal and psychiatric care to address the underlying behavioral disorder and reduce the risk of recurrence in trichobezoar-related GOO.

Introduction

Bezoars are concretions of undigested or partially digested materials accumulating in the gastrointestinal tract, potentially leading to obstruction or other serious complications. The word ‘bezoar’ derives from the Arabic term ‘bazahr’, historically used to describe substances believed to have medicinal or antidotal properties [1]. In humans, bezoars are classified based on their composition, including trichobezoars (hair), phytobezoars (plant fibers), or combinations thereof [2]. Though rare, bezoars can cause significant morbidity, including bleeding, obstruction, or perforation, with mortality rates reported to be ≤ 30% in severe cases [3]. Pica, the compulsive ingestion of non-food substances, is an uncommon but important predisposing factor, particularly in children and adolescents [4, 5].

This report details the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of a trichobezoar-related gastric outlet obstruction in a 17-year-old girl with a longstanding history of hairball ingestion.

Case report

A 17-year-old girl presented with complaints of abdominal pain, repeated vomiting, and inability to tolerate oral intake. According to her caregivers, she had a history of pica, specifically ingesting hair materials over several years. Physical examination revealed a distended and tender abdomen, with a large, firm mass palpable from the left hypochondrium extending towards the right upper quadrant.

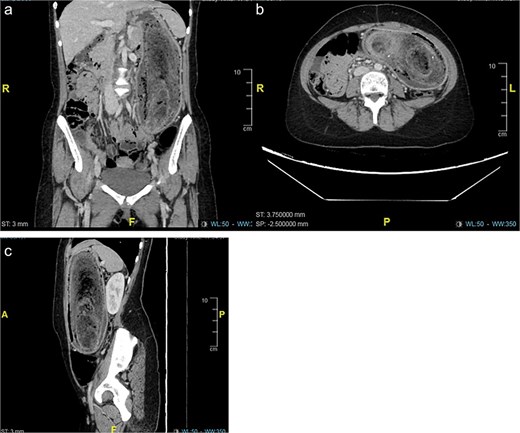

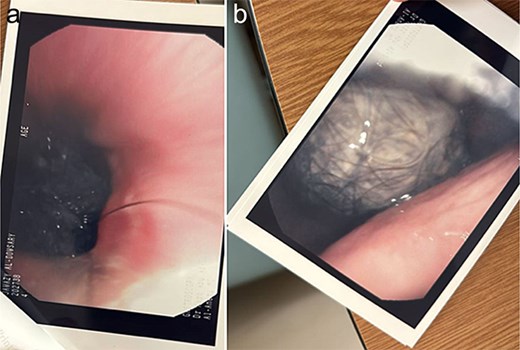

Baseline laboratory tests were within normal limits. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen confirmed the presence of a sizable bezoar extending from the stomach into the duodenum, consistent with gastric outlet obstruction (Fig. 1). Diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a large mass of hair occupying the stomach and extending beyond the pylorus (Fig. 2).

(a–c) Computed tomography (CT) revealed a distended stomach with large endoluminal mass of heterogeneous material likely representing trichobezoar. Mucosal hyper-enhancement of the stomach.

(a and b) Upper gastroscopy revealed a trichobezoar at the lower of gastroesophageal junction and within the stomach.

Due to the bezoar’s extensive size, endoscopic removal was not feasible. Consequently, the patient underwent an open surgical procedure under general anesthesia. An upper midline laparotomy was performed, followed by a gastrostomy on the anterior stomach wall. A large hair bezoar, extending from the stomach into the pylorus, was carefully extracted intact (Fig. 3). Post-extraction endoscopic inspection ensured the duodenum was free of residual foreign material. The gastrostomy was closed in two layers with absorbable sutures, and the abdomen was closed in standard fashion. The duration from presentation to surgery was within 3 h.

(a–c) Revealed gastrostomy on the anterior stomach wall. A large hair bezoar extending from the stomach into the pylorus was carefully extracted intact.

The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the fourth postoperative day. At follow-up, her symptoms had resolved, and no recurrence of pica behavior was observed. She was referred for psychiatric evaluation and behavioral therapy to prevent future episodes.

Discussion

Bezoars represent a rare etiology of gastric outlet obstruction, resulting from the accumulation of foreign material resistant to digestion and gastric emptying [6]. The prevalence of gastric bezoars is estimated at < 0.5%. Common types include phytobezoars and trichobezoars, while other rarer forms such as pharmacobezoars, lactobezoars, metal bezoars, and plastic bezoars have been reported [7]. Plastic bezoars form when indigestible plastic materials accumulate, a phenomenon seen in patients with pica. These accumulations can lead to large concretions that may even extend into the small bowel, causing complications such as the Rapunzel syndrome [8].

Predisposing factors for bezoar formation include previous gastric surgeries, such as partial gastrectomy or vagotomy with pyloroplasty, which affect gastric motility and emptying. In children, associations with psychiatric disorders, developmental delay, and pica are well documented [9, 10].

Clinical symptoms typically remain subtle until the bezoar reaches a size large enough to cause obstruction. Common presenting features include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and palpable abdominal masses. Severe complications may include gastric ulceration, pancreatitis, jaundice, or even perforation [11].

Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical suspicion and imaging studies. Plain abdominal radiographs may reveal a mass, whereas CT scans provide a more definitive visualization of the bezoar’s size, location, and extent. Endoscopy plays a dual role in diagnosis and possible therapeutic intervention [6, 12].

Treatment options are determined by bezoar size, composition, and associated complications. Smaller phytobezoars may respond to enzymatic dissolution or chemical therapies such as Coca-Cola® lavage, while mechanical fragmentation or endoscopic removal can be attempted. Larger or complicated bezoars, including hairball bezoars, often require surgical removal via laparotomy or laparoscopy [8, 11].

Literature on trichobezoars is limited but highlights the challenges in management due to their size, consistency, and extension into the bowel. Previous case reports have described similar presentations requiring surgical extraction, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary care, including psychiatric management, to prevent recurrence [13–15].

Conclusion

This case illustrates the significant medical challenges posed by a trichobezoar that causes gastric outlet obstruction, particularly in pediatric patients with underlying pica. Early diagnosis, prompt surgical intervention, and integration of psychiatric care are essential to address both the physical obstruction and the behavioral causes to prevent recurrence. Future efforts should focus on increasing awareness and developing standardized treatment protocols for such rare presentations.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.